A Decade of Maritime Security

The Yaoundé Code of Conduct Has Had Successes — and Has Room for Growth

CAPT. TAHIR NGADA, NIGERIAN NAVY

The importance of the Gulf of Guinea to Africa and the wider world can hardly be overstated. With 6,000 kilometers of coastline touching 19 littoral states from Senegal to Angola, the gulf is rich in natural resources and strategically important.

It is a vital corridor for commerce where shipping volume increased by 59% between 2006 and 2020, according to U.N. Conference on Trade and Development statistics. It also holds energy resources, producing 3.1 million barrels of crude oil per day, or about 3.8% of the global total. It is rich in aquatic life, with fisheries that produced about 3.4 million metric tons of seafood in 2020, up nearly 10% from 2013.

Despite that, the region faces threats that could undercut its potential. Illicit trafficking, illegal fishing and piracy have plagued certain areas. And, historically, countries have struggled to seamlessly share information, exchange knowledge and cooperate across the maritime domain. Bad actors looked for weak spots and exploited them.

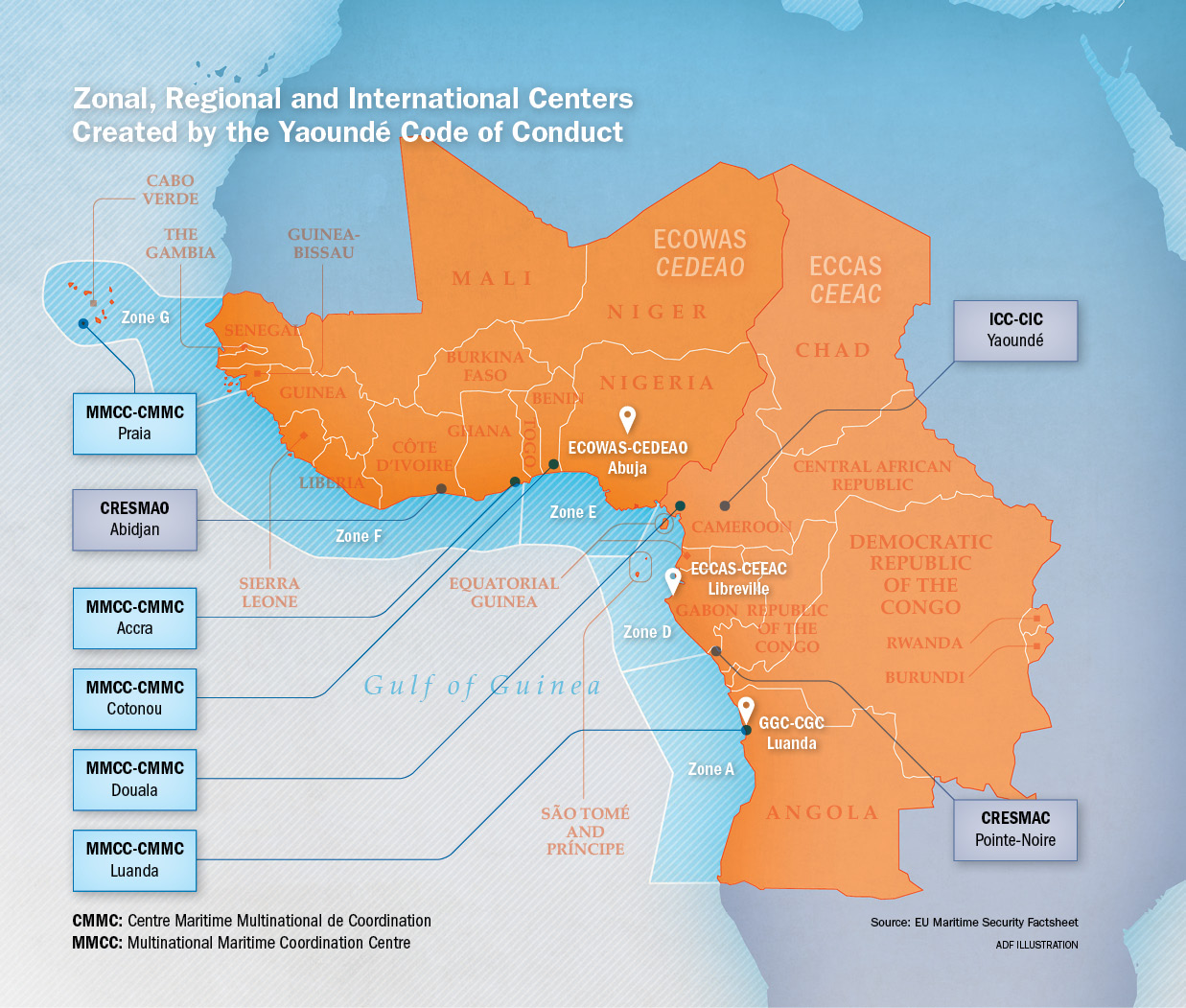

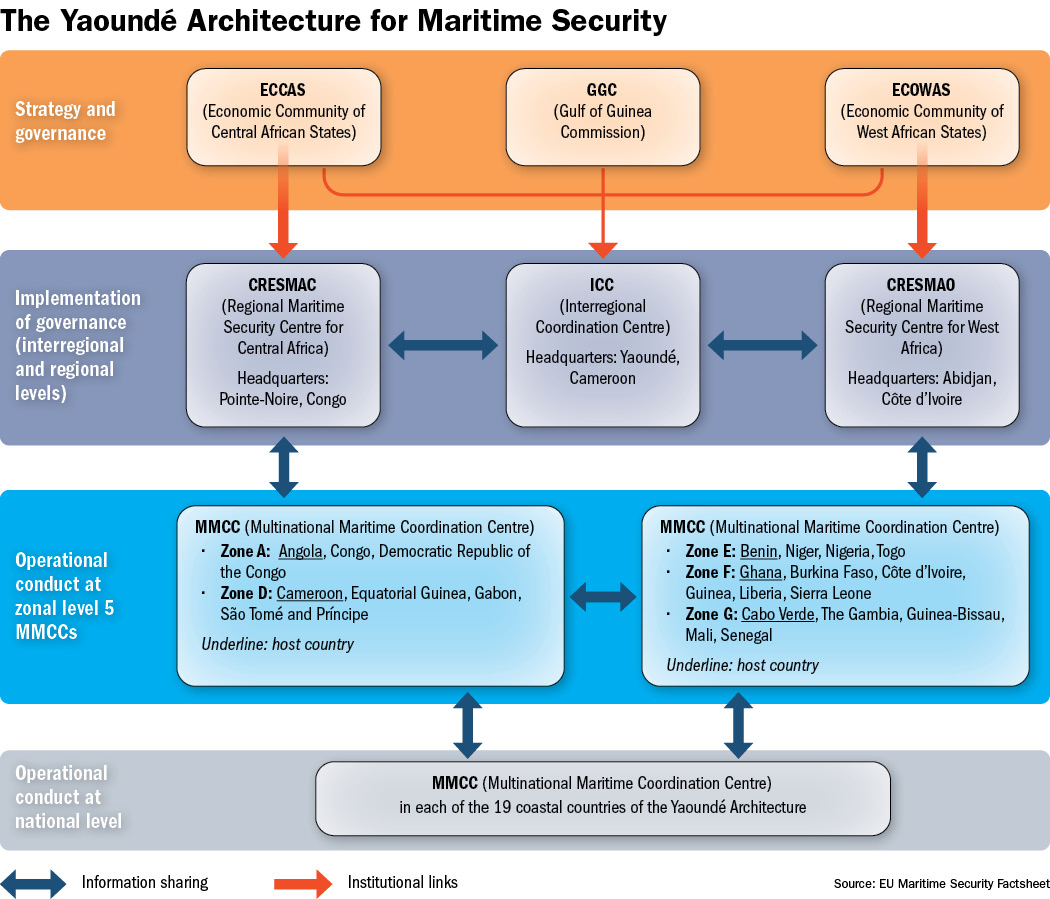

In June 2013, the countries of the region attempted to rectify this with the Yaoundé Code of Conduct, a comprehensive response to the need for unified approaches to combat maritime security challenges and transnational organized crime in the gulf. The code, which consists of 21 articles and was signed by 25 nations, established an architecture for multinational, regional and extraregional collaboration in maritime governance. As the Yaoundé Code commemorates its 10-year anniversary, it’s an ideal time to highlight some notable achievements and potential action areas that could improve cooperation and help the code fulfill its great promise.

Legal Reform

The Yaoundé signatories recognized that maritime laws too often were outdated and inadequate to confront evolving threats. The Yaoundé Architecture was intended to support countries as they put in place legal reforms. For instance, the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) Global Maritime Crime Programme has worked with nations to examine laws, identify required upgrades and support changes that allow for “legal finish,” a term that refers to moving cases from arrest through the court system toward successful prosecution.

Cabo Verde, Liberia, Nigeria, Senegal and Togo now have maritime laws to prosecute piracy, a crime that often has gone unpunished due to nonexistent laws. New laws have been used to prosecute pirates in Nigeria and Togo. Other countries such as Benin, Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana are enacting reforms. In December 2022, Cameroon signed its maritime security law, which targets piracy and maritime terrorism. Other countries such as Angola, the Republic of the Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Gabon are trying to upscale maritime legal reforms. Another milestone reform is the Economic Community of West African States Supplementary Act for the transfer of piracy suspects, which would facilitate multinational maritime security operations.

Information Exchange

Before 2013, gaps in information sharing between maritime law enforcement practitioners posed a fundamental problem. Countries had a limited picture of the maritime domain and often were unaware of activity outside their own exclusive economic zones. Conditions have greatly improved, allowing member states to exchange information. This is underpinned by the Yaoundé Architecture, which lets information flow from zonal coordination centers in each of the five cooperation zones up to regional centers (the Regional Maritime Security Centre for Central Africa in Pointe-Noire, Republic of the Congo, and the West Africa Regional Maritime Security Centre in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, and then to the Interregional Coordination Centre in Yaoundé. Individual national maritime operations centers also are connected to the system.

The Yaoundé Architecture Regional Information System (YARIS), a secure digital monitoring tool developed through partnerships with the European Union Gulf of Guinea Interregional Network, enhanced the capacity for seamless information exchange. It became operational in 2020. YARIS lets members securely share documentation, logs, photos, recordings and other information. It also lets users aggregate data from surveillance systems such as radar and satellites to identify suspicious vessels. Additionally, the system offers secure communication via chat, email and videoconferencing so users can exchange information and coordinate action.

The Yaoundé Architecture calls for developing and improving the skills, knowledge and abilities of maritime law enforcement practitioners. Centers of excellence have accelerated training and education and supported exercises by delivering courses tailored to meet identified needs. In 2022, for example, the Yaoundé Architecture Training Organisation delivered more than 520 cumulative days of capacity-building packages across the gulf, covering topics such as maritime domain awareness (25% of training days), maritime governance (12%), maritime law enforcement (35%) and maritime interdiction operations (28%). The increasing commitment to capacity-building initiatives is transforming beneficiaries’ attitudes and job performance. In a bid to deepen the coordination of capacity building, the UNODC is supporting the Interregional Coordination Centre with an integrated database management system. It is geared toward guaranteeing data availability, accessibility, accuracy, consistency and clarity.

Combined Operations

Combined operations at sea, which once were infrequent, have been increasing with the support of Yaoundé Architecture centers. For instance, using the instruments of the architecture, combined patrols were conducted in Zone E in late 2021. Cameroon, São Tomé and Príncipe, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon conducted other surveillance patrols in Zone D. Another model of combined operation is the fisheries patrol with the subregional fisheries commission of Cabo Verde, The Gambia, Guinea and Senegal that is conducted biannually. Interoperability is improving with the help of multinational exercises such as Obangame Express and Grand African NEMO, along with regional events such as the International Maritime Conference and the Regional Maritime Exercise, which was organized by Nigeria in 2022.

The Yaoundé Architecture not only has stimulated important discussions about improving maritime security, it also has provided platforms for action. Nevertheless, some areas need attention to strengthen cooperation as the code enters its next decade.

Domesticating the Yaoundé Code of Conduct: The Yaoundé Architecture could be embraced by member states so that its requirements are integrated into national maritime law enforcement frameworks. Doing so would deepen the harmonization of maritime strategies, strengthen regional interoperability and reinforce responses.

Strengthening institutional capacity: Much work has been done to strengthen the institutional capacity of maritime law enforcement. However, methodologies and tools must be improved to assist member states as they strive to assure maritime security.

Criminalizing all maritime crimes: Despite progress made in criminalizing some maritime offenses such as piracy, there still is more work to be done to strengthen the establishment of universal jurisdiction by domestically codifying piracy laws to prosecute and punish the crime across the gulf. Likewise, it is necessary to criminalize actions such as armed robbery at sea under national criminal legislation in line with the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea legal framework and other relevant international statutes. Other maritime and transnational organized crimes need to be defined in relevant laws with appropriate penalties. The goal is to ensure that there is an “end-to-end” connection from maritime interdiction operations to prosecution.

Formalizing shiprider agreements: Article 9 of the Yaoundé Code of Conduct allows for maritime law enforcement officers from one country to be aboard another country’s vessel. This coordinated approach enables countries to jointly conduct maritime law enforcement, which is helpful when some countries have limited capacity. The development of shiprider agreements between partners would further consolidate working relationships between countries toward improving critical multilateral collaboration.

Resourcing of Yaoundé Architecture centers: Putting the Yaoundé Architecture centers fully into use remains unfinished, particularly in terms of human and material resources. To effectively optimize the Yaoundé structure, resourcing needs to be well articulated to boost the operational capacity of the centers, while also solidifying multilateral cooperation toward sustainable maritime governance in the gulf.

The Path Ahead

Multilateral cooperation is a potent tool for achieving goals in maritime governance of the gulf. There is evidence that it is effective. Piracy in the gulf is declining with 81 incidents reported in 2020 and only 34 incidents in 2021. In the first nine months of 2022, there were only 13 reported incidents, according to the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. The next decade of the Yaoundé Code of Conduct must expand on the achievements made while paying particular attention to the underlying structural issues that hamper success. The gulf is a precious resource. The partnerships and vigilance made possible by the Yaoundé Code of Conduct and the security architecture it created can ensure that this resource is there to benefit generations to come.

About the Author: Capt. Tahir Ngada is a seaman officer in the executive branch of the Nigerian Navy. He works as a United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Global Maritime Crime Programme training consultant and is deployed at the Interregional Coordination Centre in Yaoundé. Ngada has a bachelor’s degree in chemistry from the Nigerian Defence Academy, a diploma in national security from the United States Naval War College and a master’s degree in international relations from Salve Regina University in Newport, Rhode Island. Ngada also has a master’s degree in countering organized crime and terrorism from University College London.

About the Author: Capt. Tahir Ngada is a seaman officer in the executive branch of the Nigerian Navy. He works as a United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Global Maritime Crime Programme training consultant and is deployed at the Interregional Coordination Centre in Yaoundé. Ngada has a bachelor’s degree in chemistry from the Nigerian Defence Academy, a diploma in national security from the United States Naval War College and a master’s degree in international relations from Salve Regina University in Newport, Rhode Island. Ngada also has a master’s degree in countering organized crime and terrorism from University College London.

Comments are closed.