Morocco Finds Success in Rehabilitating Prisoners

The Three-Step Moussalaha Program Helps Extremists Rethink Their Views and Reenter Society

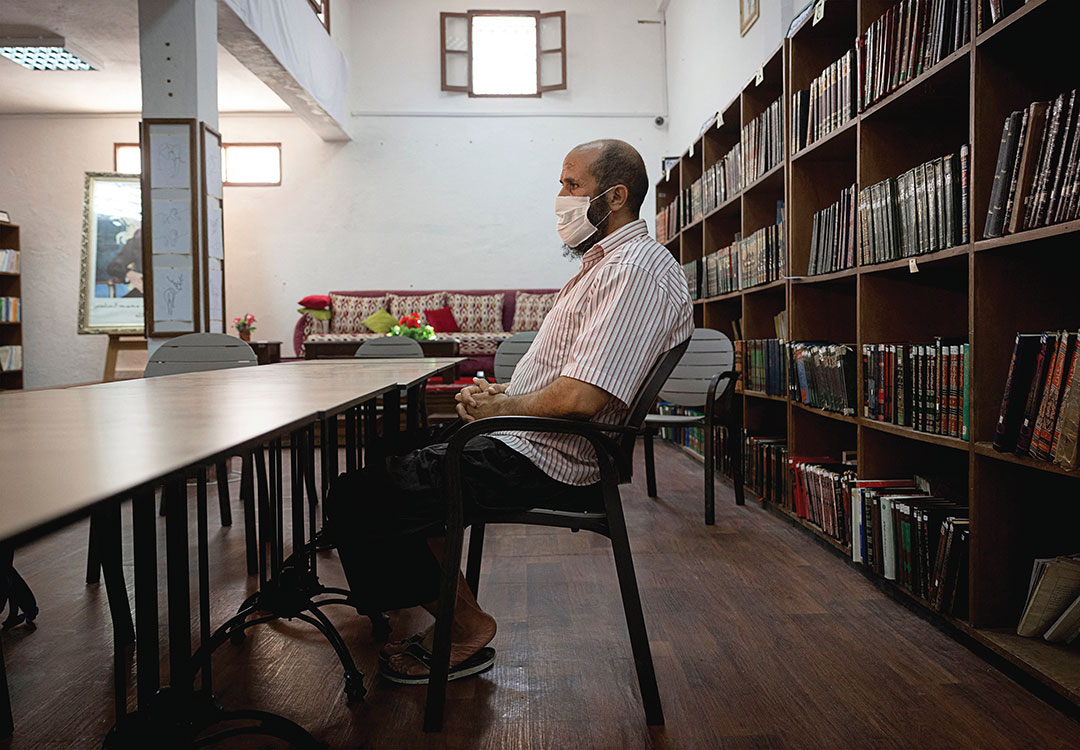

ADF STAFF | Photos by AFP/GETTY IMAGES

Morocco is an unlikely place for the rehabilitation of imprisoned extremists. The Global Terrorism Index for 2022 ranks Morocco 76th among countries affected by terrorist threats, making it one of the safest countries in Africa.

A 2003 terrorist attack in Casablanca, in which 45 people were killed, galvanized the country against extremists. After the attack, which consisted of five near-simultaneous bombings, the country tightened its borders and added new laws to its legal counterterrorism framework, including expanding the definition of terrorism to include incitement.

The 2022 terrorism index noted that “despite more than 1,000 Moroccan nationals joining the Islamic State and other terrorist groups in war zones, the country dismantled more than 200 terrorist cells and made more than 3,500 terrorism-related arrests over the past two decades, thereby possibly avoiding more than 300 planned terrorist actions.”

Since the Casablanca bombings, Morocco has worked to counter radical groups. The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace reported that between 2002 and 2018, officials arrested more than 3,000 alleged extremists, with 186 terrorist cells dismantled, including 65 cells linked to the Islamic State group.

Despite the country’s current safety, it has implemented a three-part program for rehabilitating imprisoned extremists. The program is called “Moussalaha,” which is Arabic for reconciliation. It offers imprisoned extremists mental and social help to rehabilitate them and return them to society, including finding jobs and setting up households.

The program launched in 2017 and is led by Morocco’s Directorate of Penitentiary Administration and Reinsertion service with several partner organizations, including the Mohammedia League of Scholars and the National Human Rights Council. The program since has begun allowing women to participate.

Counterterrorism expert Ido Levy was quoted in Morocco World News as praising the country’s “scientific approach” to combating terrorism and extremism through religious reeducation, professional training sessions, and what some experts associated with the program describe as security “spiritual immunization.”

The goal is to get extremist prisoners to begin to question their own beliefs. The three-month program is based on three main pillars: reconciliation with the self, with religious text and with society.

According to some participants, the three pillars mean “renouncing violence, accepting pluralistic interpretations of religious texts, and recognizing the legitimacy of the regime,” Carnegie reported. “The apparent success of the first cohort in July 2017 — several participants had their prison sentences shortened or even received a royal pardon — encouraged scores of former jihadis to join this initiative in the hope of leaving prison.”

ARRESTED AFTER 2003 ATTACK

The story of Mohamed Damir, a 49-year-old Moroccan former extremist and father of three, illustrates how the program is intended to work, according to a story in The Africa Report.

After the 2003 Casablanca attack, Damir was arrested for his association with extremist groups. He was sentenced to death even though he had not participated in the attack. He was 26 at the time. His death sentence later was commuted to 30 years in prison.

What had gotten Damir noticed was his habit of visiting unarmed groups and mosques where extremists made inflammatory speeches. He now blames his then-radicalization on a “lack of maturity combined with a lack of scientific and cultural background.”

“His first years in prison reinforced his radicalisation; he continued to learn passages of the Koran by heart, without trying to contextualise or interpret them,” the authors wrote. “Then came loneliness and doubt. Alone with himself, Damir began to question the dogmas he had mechanically memorised and took steps to study at a distance.”

He began changing his life by studying international law, but being imprisoned, he could not attend classes. He nonetheless became a committed student and went on to study sociology, psychology and theology. He told The Africa Report that he read more than 1,500 books in three languages during his time in prison.

He became a candidate for the Moussalaha program, which consisted of an extensive economic and social rehabilitation curriculum. He also was given a custom-made individual project to become independent and learn how to manage a home.

After completing the program, he was released from prison after serving 15 years. As a condition of his release, he agreed to personal counseling. He said that like almost all of the released inmates in the program, he has found “a path to peace.”

“This is an undeniable success, far from the controversies raised in Europe by de-radicalisation programs,” he said, according to The Africa Report article.

TRAINING IMAMS

Part of the credit for the success of the program goes to Moroccan King Mohammed VI, who has special authority in his country as “Commander of the Faithful,” in developing dialogues for dealing with extremists.

Along with his partners in West Africa and the Sahel, the king set up the Moussalaha curriculum for training imams at the Mohammed VI Institute. The institute is unusual as a Muslim center of learning in that it accepts women as students.

Maghreb Arab Press reported that setting up such a program for convicted terrorists “has a strong social impact, testifying to the particular interest that the King gives to the future of incarcerated citizens.”

The program, the newspaper noted, is an illustration of the king’s “firm determination to ensure convicts, without any discrimination or exception, an adequate socio-professional integration after their release.”

General Delegate for Prison Administration and Reintegration Mohamed Salah Tamek told Morocco World News that the program is based on “the authentic precepts of Islam, as a religion of moderation, middle ground, openness, and tolerance.”

“This is a unique program at the global level, especially since it has been praised by many regional and international partners,” Tamek said.

Damir told Arab Weekly that his reeducation included reading the works of philosophers Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Voltaire, some of whose ideas “are not far from the spirit of Islam.” He noted that many extremists only realize they need to abandon their violent views “once they find themselves alone” in a prison cell.

LOOKING FOR A JOB

A former prisoner named Abdellah El Youssoufi, who is now in his early 30s, left Morocco for Tunisia in 2011 looking for a job, according to The Africa Report.

In Tunisia, he became influenced by the preaching of fundamentalist Muslims, who he said were not bothered by local authorities. He said the fundamentalists offered him a job and encouraged him to speak out. He became an outspoken critic of his native country, blaming it for his poverty and his lack of professional prospects.

A video of one of his criticisms came to the attention of Moroccan authorities, who contacted their counterparts in Tunisia. El Youssoufi says he was arrested and interrogated in Tunisia for 10 days before being sent back to Morocco, where he was sentenced to three years in prison in 2014.

His incarceration, he told reporters, forced him to review his life and reflect on what he had learned during his years in the extremist movement. He saw “the limits of the responses provided by these movements to the political and social problems of our countries, as well as their contradictions with Islam and the message of our Prophet.”

El Youssoufi took part in the Moussalaha program and, like Damir, described it as a maturation process.

“Moussalaha was a chance and a golden opportunity for me to start a new life, on a healthy and balanced basis,” he said. “But it was preceded by a long work of self-questioning, a personal effort to turn the page of this period which is for me a failure at all levels.”

His story also has a happy ending: He now has a degree in computer science.

Groups Devise Guidelines For Deradicalization

A two-day forum in 2010 produced a “best practices” guide for countries to use in drawing up programs for deradicalization of former extremists.

The guidelines were the work of the International Peace Institute, the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Arab Thought Forum. The guide, “A New Approach? Deradicalization Programs and Counterterrorism,” drew from programs in eight Muslim-majority countries. The guidelines include:

- Do not regard deradicalization as a panacea. Although military and other “hard” counterterrorism programs aren’t an answer by themselves, neither are deradicalization programs. Deradicalization often is described as just one part of a holistic counterterrorism approach; it will meet with only limited success when deployed in isolation.

- Pay attention to context. What is appropriate for, and successful in, one context might not be suited to another. The time frame also might be significant: Deradicalization projects that fail or are rejected in some circumstances might be adopted in other times and places with success.

- Incorporate improved aftercare into programs. Most successful programs include follow-up or monitoring. This includes frequent contact with program tutors and daily text message reminders not to fall back into radical habits, and counseling and support.

- Improve vetting of potential beneficiaries. Recidivism is a persistent problem even for criminals not involved in terrorism. Better vetting of potential beneficiaries and improved aftercare help lower recidivism rates.

- Devise and improve ways to measure success. A recurring problem with terrorist deradicalization is measuring and quantifying the successes and failures of programs. It is difficult to compare programs, but it is important to understand reasons for success and failure.

- Tailor the approach. It is important to tailor prison policy to the situation at hand to assess whether prisoners should be isolated or allowed to mix with each other and with leaders. This furthers the argument that prospective beneficiaries for deradicalization should be examined on a case-by-case basis.

- Involve communities affected by radicalization. If the community doesn’t accept that deradicalized individuals are no longer a threat, programs will fail and will lack credibility. Similarly, successfully deradicalized people can be used in programs to great effect.

- Use incentives with care. Many deradicalization programs benefit from enticing people to leave terrorism via incentives that can help stabilize their lives. These incentives can be financial and measures such as reduced prison sentencing. But incentives can fail when societies view them as ways of “rewarding” criminals.

Comments are closed.