ADF STAFF

For centuries, scholars have studied how best to prepare Soldiers to make ethical decisions. Why do some units choose to violate laws by looting or abusing civilians? Why do others choose to put themselves in harm’s way to save a life? At the extreme, why do some troops plot and carry out coups while others steadfastly refuse to become involved in politics?

For those who have tried to mold ethical Soldiers, it comes down to one word: professionalism. Some militaries embody the highest values of their profession while others fall short.

“It is imperative that the institutions of the military be professionalized through training and education so that the military can understand its place in the society and understand that it has a role that is so important to maintain stability in the country,” Gen. Robert Kibochi, chief of the Kenya Defence Forces, told ADF.

Establishing that professional culture is not always easy. Militaries use different strategies to weave ethics into their training and build a durable culture that emphasizes respect for the rule of law.

Higher Education

Professional military education (PME) institutions can help instill an ethical culture within the armed forces. According to a study by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies (ACSS), there may be a link between PME institutions and coup prevention. The ACSS study found that of the four West African countries that had coups since 2020 –– Burkina Faso, Chad, Guinea and Mali –– none had a war college or defense college. Only Mali has a command and staff college.

Some military professionals believe there is a connection between the values taught at these institutions and respect for constitutional order and the rule of law.

“Professional military education helps to shape strategic leaders in decision-making and strategic leadership skills,” said Brig. Gen. Daniel Kuwali, commandant of the Malawi Defence College. “This trickles down to the troops under your command.”

Kuwali said educated military officers have the tools needed to lead disciplined units.

“In that way you tend to develop an esprit de corps to make decisions that are transparent, accountable. You work as a team,” he told ADF. “Your Soldiers cannot go behind your back to take over government because they have respect for you. They have ways of resolving conflicts.”

Others caution against drawing a direct link between PME and coup prevention. Dr. Kwesi Aning, a visiting professor at Uppsala University in Sweden, said the recent upsurge in coups is a product of failures by the political class in West Africa to deliver on promises and govern. He believes coups will continue until this is corrected.

“PMEs are necessary, but they are not the bulwark against coups d’état,” he told ADF. “The resurgence in coups is reflective of the misgovernance of West African states, and we have not seen the end of it.”

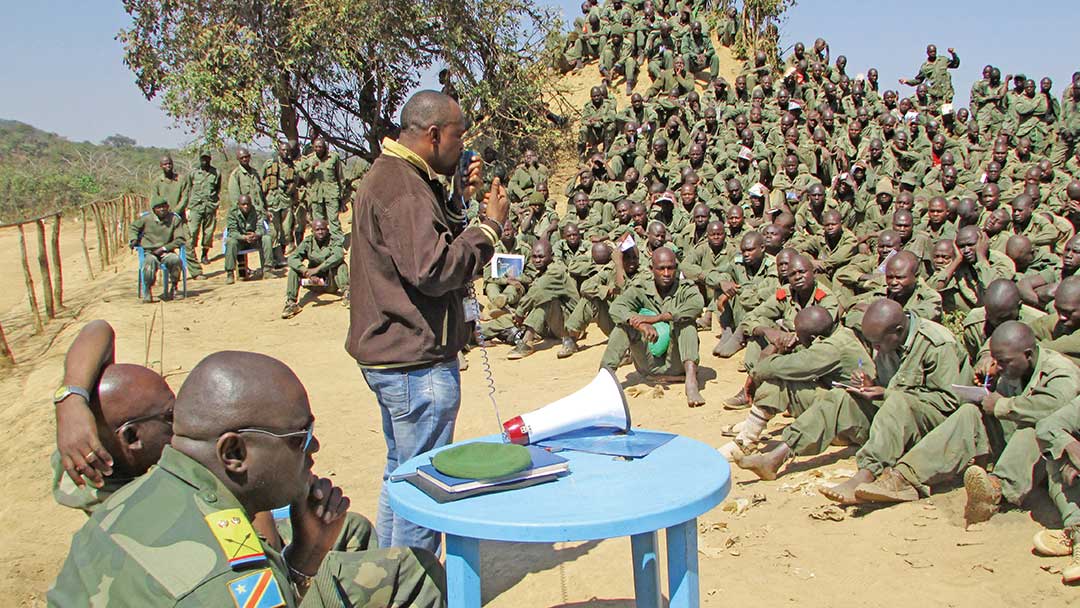

Ethics in Field Training

Ethics are not only learned and reinforced in the classroom. It has become common for predeployment training and field training exercises to replicate real-world ethical scenarios.

In one training scenario a Soldier might be surrounded by a hostile crowd. In another he or she might have to weigh civilian casualties against neutralizing a high-value target.

“The aim is to accustom military personnel to embedding these moral reflections within their execution of tactical actions in the field, in the midst of difficulties, under the pressure of time, weather and real stress,” wrote Brig. Gen. Benoit Royal of France in his essay, “Military Ethics: From Theory to Practice.” “The behavior of a Soldier in combat must be constantly influenced by the spirit and the core values we have taught them.”

The best type of training will simulate stressors such as sleep deprivation, narrow time windows and incomplete battlefield information.

“Military personnel are called upon to make moral decisions under some of the most challenging of conditions,” wrote researchers Megan Thompson and Rakesh Jetly in the article “Battlefield ethics training: integrating ethical scenarios in high-intensity military field exercises.”

Thompson and Jetly said such situations are ethically muddy. A Soldier might have to weigh conflicting values pointing to two different choices. A Soldier also might confront a situation in which any choice will harm civilians or comrades. The correct decision is rarely obvious.

“Together, these factors create ‘the threatening psychological ambiance of combat,’” they wrote.

But if such training is limited to predeployment modules or annual exercises, it will fall short, experts say. It must be reinforced throughout a Soldier’s career and become more complicated as he or she advances through the ranks.

In peacekeeping, Aning said, training must be a cyclical process that incorporates lessons learned in the field.

“When that training is done well it becomes a win-win situation, both for the troop-contributing country and its armed forces, the recipient country and then the lessons can be passed around,” Aning said. “I’m a great supporter and believer in updating the curriculum, but it must be a curriculum that is flexible, that responds to the changing needs of the peacekeeping environment.”

Trainers also should collect information on how knowledge is absorbed and used in the field. “We must develop a feedback loop,” Aning said. “How do uniformed personnel understand what they’ve been taught? How do they apply it? How do they respond to the feedback and use it as part of the learning process?”

Modeling Ethics

Ethical behavior is not only taught; it is modeled. Many military professionals cite mentors or role models as being key to their professional development.

In its Leadership Handbook, the U.S. Army encourages building careerlong mentor relationships. A large survey of senior noncommissioned officers and commissioned officers found that 84% report having a mentor over the course of their careers. These don’t necessarily have to be superior-subordinate relationships. They can be between peers.

“A trusted advisor plays a significant role in shaping a Soldier’s character and development,” the U.S. Army wrote. “Mentors can assist at different stages of a Soldier’s career; a junior Soldier striving to become an NCO up to when they are ready to retire to civilian life.”

Learning also is not a one-way street. “Mentors also learn from their mentees; a mentee can be a leader and not even realize it,” said Cris Arduser, program manager of the U.S. Army Sustainment Command Mentoring Program. “Part of what mentors do is to help the mentee realize the leadership skills they already possess and how to work with those skills to create their own leadership style.”

Treated Like a Professional

When a breakdown in professionalism or an ethical lapse occurs, it usually is not isolated. It is part of a systemic failure. Soldiers who loot or accept bribes often say they have not been properly paid. Soldiers who abandon their posts or refuse to follow commands sometimes complain of being underequipped. And those who subvert the chain of command complain that the selection process for promotion is corrupt or unfair.

In countries where coups have taken place, Aning said, it is common for things such as recruitment and promotion to be connected to ethnicity and political affiliation. This has a corrosive effect on the military.

“Over time, the institutional ethos is undermined,” he said. “Political decision-making and affiliations begin to play a critical role. And eventually that organic relationship between the political leadership and the military establishment begins to break down.”

A broken system can lead to unethical behavior by the military.

“A lot of people within the military begin to feel as if those who ought to be leading them don’t speak on their behalf,” Aning said. “They are more concerned about speaking for their political masters. And when that breakdown happens internally within the armed forces, then issues of command and control begin to break down, issues of disrespect for civilian authority begin to break down.”

Ethics researchers believe the state has an obligation to its Soldiers just as the Soldiers do to the state.

“The military is entrusted with violent power by the state it defends,” wrote Kula Ishmael Theletsane of Stellenbosch University in South Africa. “The state, therefore, must be able to trust its military with its security. As the military acts on the authority of its state, the state’s image also depends on the military’s international reputation.”

Careerlong ethical training helps Soldiers make these decisions, particularly in complex peacekeeping, humanitarian aid and counterinsurgency missions.

“Military leaders must be able to shift cognitively between applying coercive force and employing restricted force, between securing the interests of the nation and the interests of the international community,” Theletsane wrote. “Ethics prepares officers to lead armed forces in such ambiguous situations.”

Comments are closed.