ADF STAFF

Small clouds of red dust rose from the Russian mercenaries’ truck as they rode into the heart of Bambari, promising food to the hungry.

In the sweltering heat, dozens lined up along an earthen road in the Central African Republic’s (CAR) fourth-largest city.

Instead of food, they were given handmade signs and ordered at gunpoint to protest MINUSCA, the United Nations peacekeeping mission in the CAR, demanding that the U.N. leave the city it liberated from rebels in late 2020.

It didn’t add up for Nigerian journalist Philip Obaji Jr., who has reported extensively on the infamous Russian private military company (PMC) called the Wagner Group as it has expanded its operations in Africa.

“Multiple sources in CAR told me the anti-U.N. protest in the town of Bambari was a false-flag operation staged by Wagner mercenaries,” Obaji told ADF. “Before significant numbers of Wagner left for Ukraine, I reported on new taxes on agricultural products that they’ve imposed and pocketed.”

Obaji also received reports that Russian mercenaries massacred civilians in the villages of Mouka, Yangoudroudja, Aïgbado and Yanga.

Accusations of atrocities follow the Wagner Group like a shadow.

In the CAR, mercenaries are but one spoke in the wheel of Russia’s hybrid approach that has combined hard and soft power for more than four years.

“CAR is currently in a state of state capture,” Mattia Caniglia, a fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, told ADF. “The level of penetration we are witnessing now is enormous.

“At the moment you have a situation that is perfect for what Russia does.”

A Country Ripe for Exploitation

Russian operatives have been in the CAR since 2017 after crossing its porous northeastern border with Sudan. They have entrenched themselves by taking advantage of widespread instability, anti-French sentiment and a president in Faustin-Archange Touadéra who was on the verge of being overthrown by rebels.

In more than four years, Russia has gained unprecedented access to the levers of governmental power and used it to spread propaganda, leaving many citizens uncertain of whom to trust in the country.

Caniglia describes Russia’s approach in Africa as opportunistic and strategic, stressing the importance of distinguishing between its two pillars — official and unofficial activities.

“In the unofficial, we find a lot of asymmetric, hybrid stuff,” he said. “In the official, we find that, too, but mostly it’s about bilateral agreements, military training, weapons deals and more.”

Russia’s approach has been on full display in the CAR.

In 2018, Touadéra installed Kremlin-linked Valery Zakharov, a former Russian intelligence officer, as his national security advisor.

The European Union (EU) has called Zakharov “a key figure in … Wagner Group’s command structure” who keeps “close links with the Russian authorities.”

The level of power Wagner achieved in the CAR may have surpassed even its expectations.

“This is something rather unprecedented,” Caniglia said. “But again, all of the conditions were right there in CAR. They achieved leverage that in any other place they were not allowed to have.”

Another Touadéra ally, Alexander Ivanov, also reportedly has close ties to Wagner.

As the official representative of Russian military trainers in the CAR, Ivanov leads an independent “peace advocacy” group called the Officers Union for International Security (COSI).

Russia’s Defense Ministry admitted that it used Ivanov to recruit all of its trainers deployed to instruct CAR’s Armed Forces (FACA), according to Russia’s statement to a U.N. expert panel.

Using private business proxies such as Wagner and COSI provides necessary cover for Russia. Its ability to deny official involvement is a critical piece of the deliberately opaque puzzle that is Russia’s hybrid approach in the CAR.

“Their motivation is primarily financial,” Kevin Limonier, a lecturer in geopolitics and specialist in Russian-speaking cyberspace, told The Africa Report magazine. “They see Africa as a place to make money and explore new horizons.”

Russia’s hybrid model lets it exert influence with a small investment of money and manpower.

“The Russian state does not necessarily have the means to fulfill its political ambitions in Africa,” Limonier said. “It therefore relies on these networks that use unconventional methods and deny their involvement, should a problem arise.”

With the Wagner Group, problems always arise.

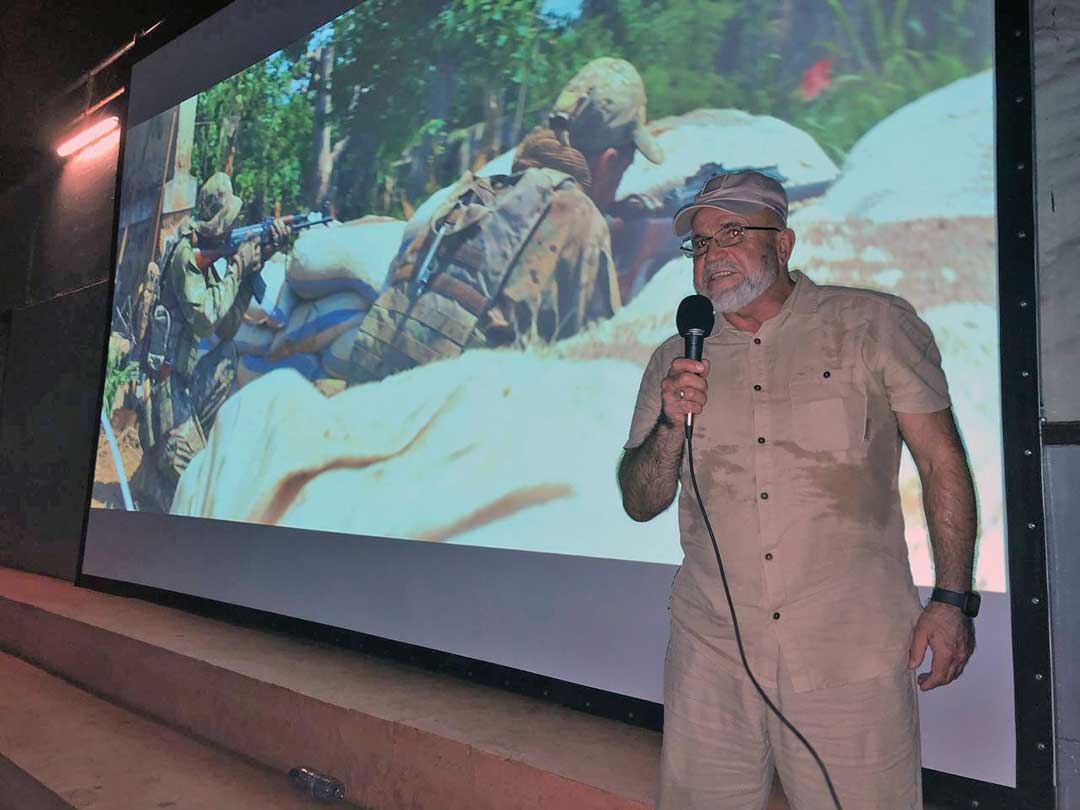

Hard Power: Trainers and Mercenaries

With an estimated 2,200 to 3,000 personnel, Wagner is the most notorious of the multiple Russian PMCs purportedly operating as trainers and security providers.

Whenever Touadéra and other high-level officials are in public, heavily armed guards in fatigues hover nearby. They travel in armored Russian vehicles and occasionally coordinate with Russian helicopters and drones.

What began as a training mission in 2018 ultimately evolved into counterinsurgency operations with Russian mercenaries in the field — in some cases commanding FACA units.

Reports of massacres at the hands of Russian mercenaries and FACA troops following their orders have destabilized the military.

In June 2020, a U.N. expert panel said it had “received numerous reports about Russian instructors who have been indiscriminately killing unarmed civilians,” using excessive force and looting in the CAR, particularly in mining regions.

The panel also said Libyan and Syrian mercenaries had engaged in combat alongside Russian trainers.

The Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights in March 2021 received reports of mass executions, torture, arbitrary detentions, forced displacement of civilians and attacks on humanitarian workers attributed to PMCs working with FACA, including the Wagner Group.

Soft Power: Information Warfare

Russia has employed several soft-power means to promote its agenda in the CAR.

Through mercenaries, shell companies and other proxies, Russia has financed local media, sponsored “anti-imperialist” influencers, produced multimedia propaganda, and run disinformation and misinformation campaigns.

Wagner Group members and associates reportedly have built playgrounds and statues to themselves. They’ve created at least two Wagner Group propaganda films in the CAR to mythologize their actions. They’ve held football tournaments and beauty contests.

Kremlin-linked oligarch Yevgeny Prigozhin, accused by the EU of financing the Wagner Group, funded the creation of radio station Lengo Songo (which means “Building Solidarity” in the Sango language) for $10,000, according to the BBC. The station has a strong pro-Russia stance, blaming the U.N. and France for the CAR’s crisis.

With Russia’s mercenaries comes a suite of media services.

“They are cheap and come as part of a package of regime-support services, including political technologies,” Mark Galeotti, an expert on Russian security affairs, said of Wagner to independent newspaper The Moscow Times.

Russian financing and media manipulation campaigns helped Touadéra win reelection in 2020 by a comfortable margin.

Zakharov reportedly oversaw the placement of Touadéra allies in key election positions, including vote tallying.

The CAR was one of eight African countries where social media giant Facebook suspended hundreds of fake accounts and dismantled what it concluded were Russian election interference campaigns. In the CAR, Russian trolls smeared the country’s African neighbors and foreign partners while propping up Russia as a liberator.

Coordinated street protests followed, targeting France, MINUSCA and the Economic Community of Central African States.

MINUSCA in August 2021 also dealt with false rumors that it was supplying rebels with land mines, even as it was deploying personnel to remove such devices.

“MINUSCA has never used mines,” U.N. forces spokesman Maj. Ibrahim Atikou Amadou told the BBC, noting that demining operations were at an impasse because of the allegations.

Diplomatic Power

Using its position on the U.N. Security Council, Russia created its first foothold in the CAR when the U.N. lifted an arms embargo, which allowed Russia to sell weapons to the country.

Russia’s more recent U.N. efforts — blocking appointments to U.N. expert panels and thereby subverting the international sanctions process — have thwarted investigations into Russia’s and its PMCs’ activities.

“It looks like Moscow wants to paralyze sanctions and panels of experts to divert attention from what Wagner is up to in Africa,” International Crisis Group’s U.N. Director Richard Gowan told Foreign Policy magazine. “So in some cases, it is simply a way of covering up some nefarious business.”

The Cost for the CAR

Securing lucrative gold, diamond and uranium concessions has been a high priority of Russian operatives in the CAR. With no government accounting of payments to Russian trainers or PMCs, experts believe mining rights are given in exchange for mercenary service.

The business of extracting the CAR’s vast mineral wealth lies with Russian shell companies such as Lobaye Invest, which is linked directly to Prigozhin and was created in October 2017, along with a subsidiary PMC called Sewa Security Services.

Léopold Mboli Fatran, the CAR’s minister of mines, gave Lobaye mining exploration permits in two regions in June and July 2018. He eventually granted permits in six regions: Alindao, Birao, Bria, N’Délé, Pama and Yawa.

Obaji and other journalists have connected massacres by mercenaries to many mining sites as the Russians attempt to secure their concessions.

Where once they were celebrated, Russians now find villagers fleeing their arrival.

“The people were relatively happy with the Russians being there about two or three years ago,” Caniglia said. “But now they know what kind of things are going down.”

The U.N. Office for the Coordination

of Humanitarian Affairs estimates that

3.1 million people — more than 60% of the CAR’s population — need urgent relief. The number of internally displaced people has risen to a record 722,000, and another 733,000 have sought refuge in other countries.

Such results after more than four years of Russian involvement in the CAR could serve as a warning to other African countries considering their mercenaries, Caniglia said.

“But this is not what is happening,” he said. Some countries in the Sahel region are signaling their openness to hosting Russian forces despite the clear track record they have of causing instability. Observers are surprised these countries are not learning the lessons from the CAR of the dangers of partnering with Wagner and Russia.

“What is happening in CAR is very bad, not only in terms of the level of influence that Russian nonstate actors have on the CAR government, but also in terms of human-rights abuses and further destabilization of the security situation. But it’s not getting through. It’s just not sticking,” Caniglia said.