ADF STAFF

Armed separatist groups in Cameroon and Nigeria are joining forces in a move that is alarming officials on both sides of the border.

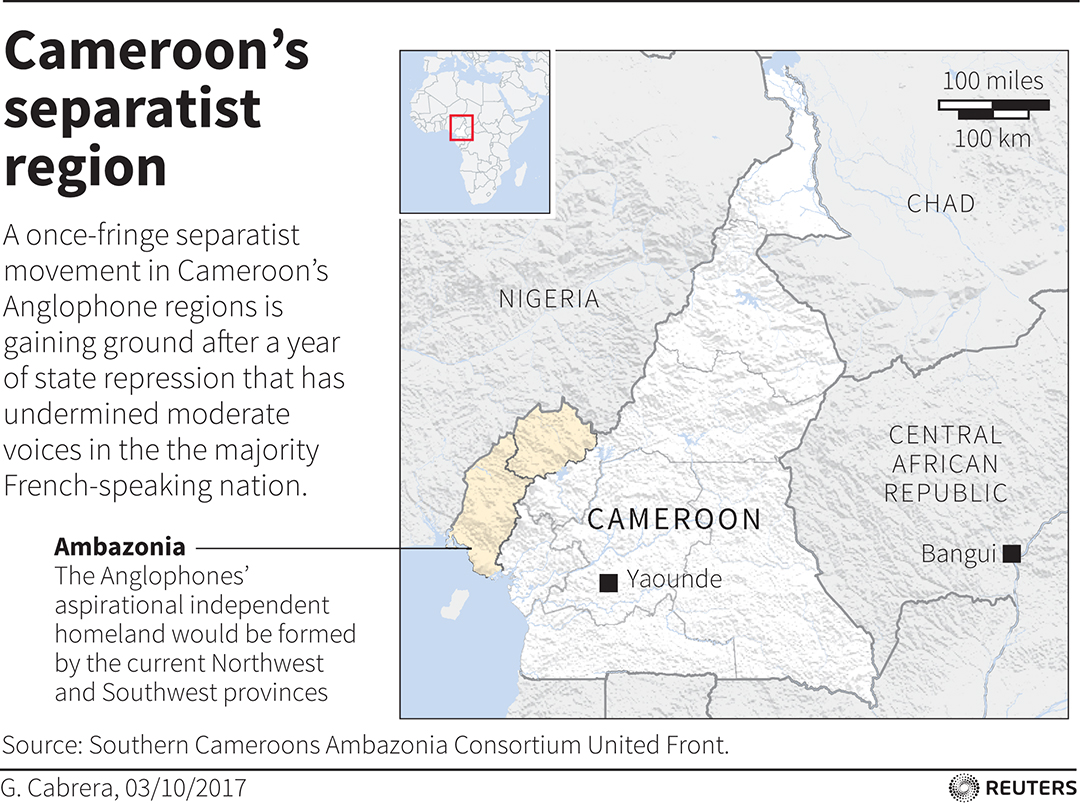

On September 16, militants in Bamessing, Cameroon, ambushed a convoy carrying Cameroonian Rapid Intervention Battalion Soldiers. The attackers were English-speaking separatists fighting for an independent state known as Ambazonia. In the attack that left 15 Cameroonian Soldiers and several civilians dead, assailants used improvised explosive devices, heavy weapons and an anti-tank rocket launcher.

Officials believe the fighters obtained the sophisticated weaponry from allies across the border in Nigeria, possibly those fighting for an independent state of Biafra.

“The separatists have used heavy weapons for the first time, in violation of international humanitarian law,” the Cameroonian Army said in a statement. “The rise in power of these terrorist groups … is largely due to their co-operation with other terrorist entities operating outside the country.”

English speakers in western Cameroon have pushed for independence for decades, arguing that they are underrepresented in government and victims of discrimination at the hands of the French-speaking majority. Since 2016, the conflict has grown in intensity with 730,000 people displaced and 3,000 killed, according to Human Rights Watch.

Across the border in Nigeria, some members of the Igbo ethnic group also have fought the central government for decades. Most notably, the group declared independence for the state of Biafra in 1967, setting off a civil war that lasted three years and cost the lives of 1 million people.

In Nigeria today, a group known as the Indigenous People of Biafra is waging a battle for independence. The group’s leader, Nnamdi Kanu, was arrested by Interpol in June outside the country and extradited to Nigeria. He faces charges of treason and terrorism and has pleaded not guilty.

These two separatist groups appear to have found common cause. In April, leaders of the two groups –– Cho Ayaba of the Ambazonia Governing Council and Kanu of the Biafran group –– held a virtual press conference announcing an alliance.

“We have assembled here today in front of our two peoples to declare our intentions to walk together to ensure collective survival from the brutal annexations that have occurred in our home nations,” Ayaba said.

The alliance also includes weapons sharing. The Niger Delta, near the Igbo base of power, is a hub for weapons smuggling. In September, Nigerian police arrested 40 arms traffickers in the border town of Ikom and charged them with supplying Cameroonian separatists with weapons, ammunition and explosives.

Oluwole Ojewale, the regional organized crime observatory coordinator for ENACT, said the flow of weapons into Cameroon not only is arming separatists in the southwest, but also Islamic extremists such as Boko Haram in the north. ENACT, an institute that researches transnational organized crime, estimates that there are more than 250 footpaths from three Nigerian states into Cameroon where traffickers can move weapons without being stopped by security forces.

“These tracks are mostly unknown to security forces, including the Multinational Joint Task Force,” Ojewale wrote in a piece for the Institute for Security Studies. “The routes provide unfettered passage for those smuggling arms into the country.”

Ojewale stressed the need for greater cooperation between the two countries to stem the tide of illegal weapons. “Cameroon and Nigeria have a history of cooperating to combat arms proliferation,” he wrote. “These efforts will need to be stepped up.”

Observers now fear further destabilization in the region on both sides of the border. In an article in Foreign Policy, journalist Jess Craig noted that, in exchange for materiel assistance, Cameroonian separatists plan to show their Nigerian counterparts how to make the region “ungovernable.” Observers also fear a rise in ethnic violence because the Igbos and Anglophone Cameroonians have both fought with ethnic Fulani herders in disputes over land.

If left unaddressed, the violence could ripple across the region.

“The lesson I take from this is … that domestic grievances, when allowed to fester, can ultimately convulse into broader conflicts and brother crises and armed conflicts, which could have devastating consequences on a transnational basis,” said Cameroonian-born political scientist Christopher Fomunyoh of the National Democratic Institute.