ADF STAFF | Photos by AFP/Getty Images

Early in the 2018 Ebola epidemic in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), contact tracers used paper forms, filling them out each day for every contact made. At the end of the day, tracers turned in the paperwork to their supervisors, who alerted doctors if any of the contacts showed signs of Ebola. The process was slow, tedious and bureaucratic.

The World Health Organization (WHO) noted that paperwork also drew unnecessary and unwelcome attention to contact tracers. Sometimes, people chased them away.

Contact tracers later traded their papers for mobile phones. They gathered data discreetly and transmitted the information to supervisors from the field, using an application called Go.Data. Epidemiologists could access the data almost in real time and act quickly.

“It is particularly focused on case and contact data collection and management,” said Armand Bejtullahu, project leader at WHO and one of the chief architects of the tool, the WHO reported on its website. “This allows the software to produce outputs, such as contact follow-up forms and dynamic visualization of chains of transmission.”

The Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network reports that Go.Data now is being used all over the world to trace COVID-19 carriers.

The DRC has deep experience fighting disease. Before COVID-19 and Ebola, the DRC endured outbreaks of AIDS. It is generally believed that HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, originated in Kinshasa, in the DRC, about 1920 when it crossed from chimpanzees into humans. In 1976, the first case of Ebola was discovered, also in the DRC.

COVID-19 originated under circumstances similar to the two other diseases, but in China instead of Africa.

Now researchers believe the response to HIV and Ebola can inform and help direct the response to COVID-19.

“As researchers who have long experience with HIV/AIDS prevention, vaccines, and therapies, some of whom also have experience with Ebola, we believe it is critical to build the response to the COVID-19 pandemic on lessons from the HIV pandemic and recent Ebola outbreaks,” wrote researchers for The New England Journal of Medicine in October 2020.

The researchers said the AIDS and Ebola epidemics proved that interventions must be based on “sound science.” COVID-19, they said, “presents an important opportunity for smart deployment of our hard-won knowledge.”

NEW RESPONSE PROCEDURES

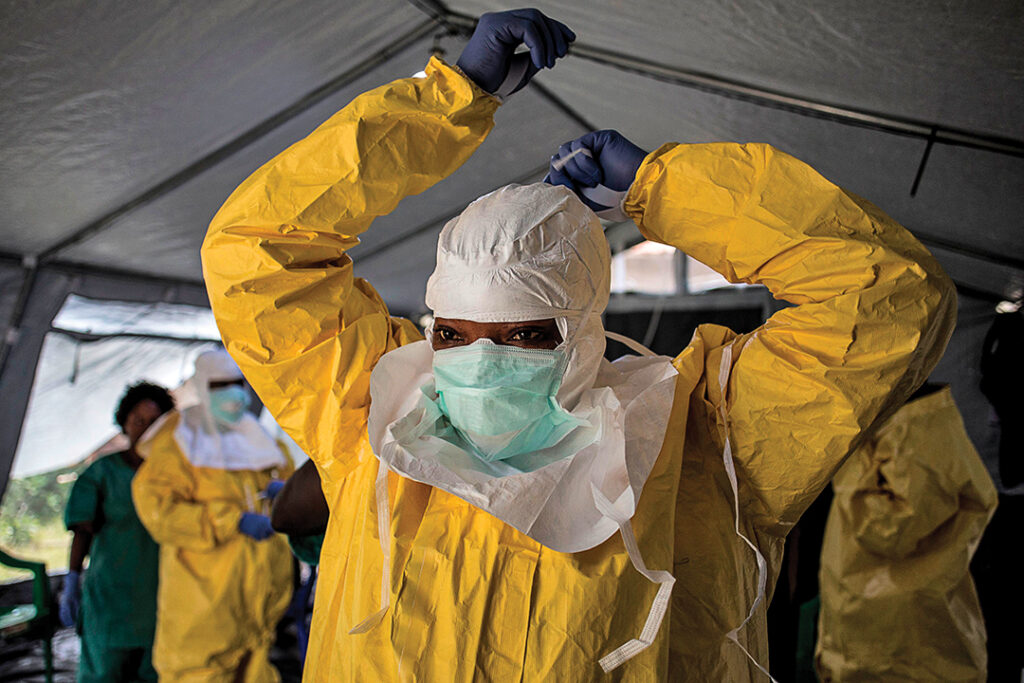

The 2014-2016 West African Ebola pandemic forced health care workers to change how they respond to disease outbreaks and other health crises. The WHO and other organizations have made these recommendations for applying those lessons to future outbreaks:

Research has to be at the heart of a health emergency response. The WHO Research and Development Blueprint was created in 2016 to trigger rapid activation of research and development during epidemics. Workers used the blueprint to fast-track effective tests, vaccines and treatments during the 2018-2020 Ebola response in the DRC.

“Integrating ethically sound, rigorous research into emergency responses ensures that the world is better prepared for the next disease outbreak,” the WHO reported.

Rapid laboratory testing can make or break a health crisis response. Faster test results mean faster access to care, which increases survival chances.

“A rapid diagnosis helps prevent the spread of the disease among the family, friends, and others in the social network of a person confirmed to have Ebola,” the WHO reported. “The faster these contacts are identified, the faster they can be vaccinated and protected from the disease.”

The community must be engaged in the response. A one-size-fits-all approach to public engagement doesn’t work. Each community is unique and wants responders who are familiar, from the area and speak local languages. Sometimes when outsiders try to help, they are met with resistance and disbelief. In many cases, science and disease control clash with local customs.

Train health care workers on disease specifics. During the DRC Ebola outbreak, a survey showed that 85% of health care workers believed they could avoid infection by abstaining from handshakes or touching. Correcting these myths was a critical part of the response, especially for health professionals.

Support survivors. During the West African Ebola crisis, survivors weren’t getting the follow-up attention they needed for possible medical, psychological and social challenges. They needed support to minimize the risk of continued disease transmission.

Depending on the disease, health care workers will need to establish follow-up protocols. Ebola survivors got monthly follow-up exams for six months and quarterly exams for a year.

Ebola survivors often have eye problems, even permanent blindness. In West Africa, eye clinics were established early on to identify and treat people.

Set up a fast-response funding mechanism. Disease outbreaks often move faster than money can be allocated for a response. As a result of the Ebola outbreaks, WHO learned to set up a rapid response called the Contingency Fund for Emergencies so that money is immediately available to jump-start a response.

The fund is surprisingly versatile. WHO has used it to respond to more than 100 events, including Ebola outbreaks, cyclones in Mozambique and the Rohingya refugees crisis in Bangladesh.

A crisis is an opportunity to build bridges. Medical crises require scientists and health care workers to work closely with the public. The AIDS epidemic showed that collaboration between researchers and the public was feasible — and necessary.

“AIDS advocates pressured scientists to act more quickly, to be more transparent, and to communicate clearly about scientific rationale and methods,” The New England Journal of Medicine reported. “The result was shorter timelines for scientific investigation, regulatory review, and implementation of effective interventions.”

Digital Changes Everything

ADF STAFF

The Ebola outbreaks solidified the value of using digital data and mobile phones as medical tools. Mobile electronic health records programs, sometimes called mHealth, offer something traditional record-keeping cannot: speed and flexibility.

In its research on the Ebola outbreaks, the Health Initiatives Foundation said that mHealth lets officials “quickly disseminate the latest information to front line health care workers.” The foundation added that increasing the speed of communication is “a general boon to any large public health response.”

In a 2015 study, the Brookings Institution noted that Ebola treatment units benefited from using digital rather than paper records, in part because paper records cannot be removed from a treatment unit. Deborah Theobald, co-founder of Vecna Technologies, which created the mHealth platform in Nigeria, pointed out, “If the patient is isolated, so is their paperwork.”

Brookings has noted that despite the benefits of mHealth, barriers in some countries will prevent the full positive impact of these technologies. Many developing nations lack the electrical infrastructure necessary to power mobile devices. And even after Ebola, many countries continue to have cumbersome health care regulations.

“It often takes an emergency situation like the Ebola crisis to make substantive changes,” the institute noted. “Success in the long term is only possible if leaders create an environment that is more hospitable to mHealth.”

Experience Means Versatility

ADF STAFF

Experience in dealing with Ebola has proven to be so valuable that Ebola “veterans” are being dispatched to COVID-19 hot spots to apply their expertise.

In early 2020, Chiara Camassa, an administration officer for the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP), was sent to Haiti as the agency’s “point person” on COVID-19 issues. Her appointment came as a result of her experience with Ebola in West Africa in 2014.

During the Ebola crisis, Camassa worked from WFP’s regional response hub of Accra, Ghana, the United Nations reported. She had to adapt quickly, and her role was expanded far beyond the distribution of food. “She was responsible for the deployment and tracking of assets, mostly generators, prefabs, sanitation structures and other equipment for treatment centers, offices and infrastructure throughout three affected countries: Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone,” the U.N. noted.

Natasha Nadazdin of the WFP said the death toll during the Ebola crisis would have been much higher were it not for her agency venturing out of its traditional areas of expertise.

“The initial thinking was this is a medical crisis and we cannot cross lines and we shouldn’t be doing things the World Health Organization (WHO) should be doing,” she said, as reported by the U.N. “But when we became aware of the potential dimensions of that crisis, then it became clear that WFP would have to get involved in a very serious way because of our logistics capacity to procure quickly and organize the supply chain.”

In a 2015 editorial, Margaret Chan, then director of the WHO, wrote: “The Ebola outbreak has taught us many lessons, among them that the response to outbreaks and emergencies must start and end at ground level — which means that certain key capacities have to be in place before launching a response, including leadership and coordination, technical support, logistics, management of human resources and communications.”

“It has also shown that the organizations working to contain outbreaks and emergencies must collaborate closely,” she added.