EDWARD A. DURELL, P.E., SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY ADVISOR, U.S. AFRICA COMMAND

Important technological innovations don’t typically come out of the blue. They are made possible by planning and support. At least 25 African countries have science, technology and innovation (STI) strategies. However, the African Academies of Sciences noted that these policies often focus solely on business and industrial development, and “social and environmental goals are not adequately integrated.”

Today, Africa’s research strengths are in agriculture, tropical medicine and infectious diseases, according to an STI implementation report. Widening the scope of research and investment could help unlock the vast scientific potential of Africa.

The continent is in the midst of a historic youth bulge with almost 60% of the population under age 25. According to the African Youth Survey 2020, 78% of young people are interested in pursuing a technology career. Global giants such as Microsoft and Google are eager to take advantage of this talent and have made major investments in Africa in recent years. A careful examination of Africa’s research and development landscape may help show where strategic investment can yield the greatest gains.

Funding Research and Development

Funding Research and Development

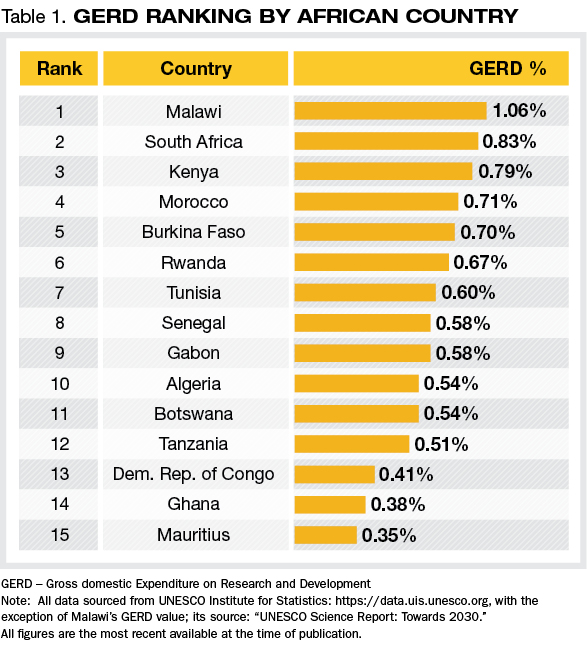

One way to measure a country’s willingness to commit resources to science and technology is to examine expenditures on research and development. GERD is a value calculated using gross domestic expenditure on research and development as a percentage of gross domestic product. The African Union has established a target of 1% GERD for its member states; by way of comparison, the United States GERD expenditure is 2.7%. Every five years the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization publishes an extensive report tracking science, technology, innovation and governance. It includes a wealth of statistics; one of them is GERD.

Data is not available for every African country, but Table 1 shows the top 15 reporting countries in terms of GERD. When viewed through the lens of regional economic communities, the strongest GERD performance came from the five-member Arab Maghreb Union. Three of its member states appear in the top 10: Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia.

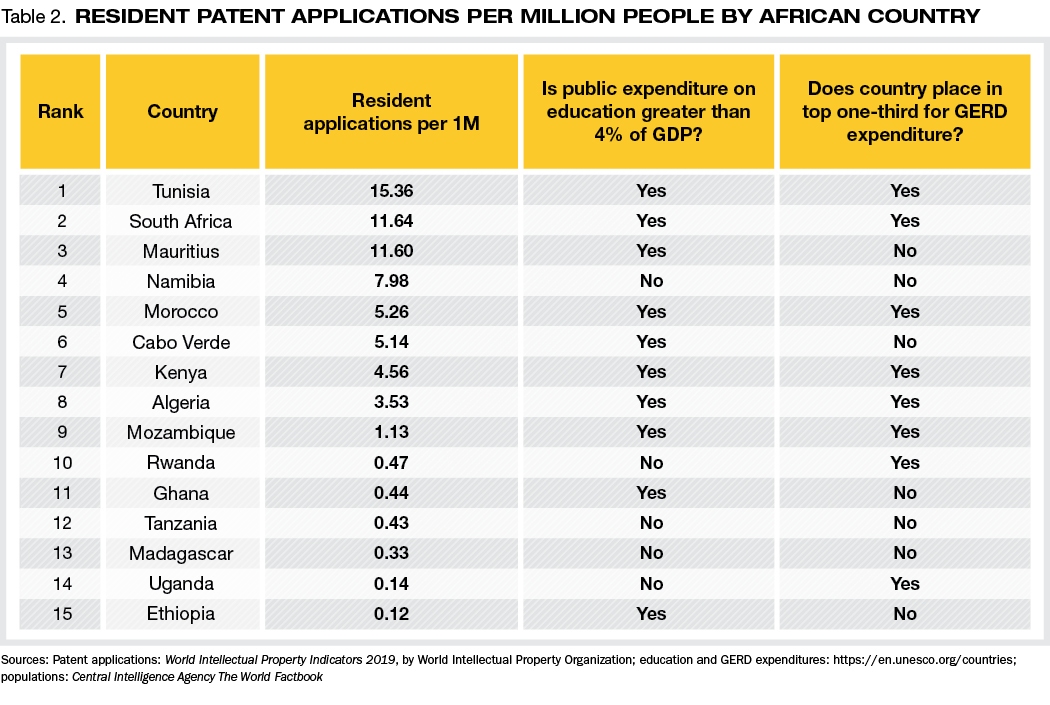

Expenditures are one indicator, but what about technological achievements? One quantifiable parameter of scientific and technological health is to use patent applications as an innovation indicator. Again, by way of comparison, the number of patents per 1 million population for the United States is 129. Table 2 shows resident patent applications per 1 million population. Data is not available for every country, and some countries use the African Intellectual Property Organization as their patent office; its application data cannot be separated out by country. Again, there is a strong performance from the five-member Arab Maghreb Union. Three made it into the top eight: Tunisia, Morocco and Algeria.

Some countries perform well in patent applications per capita even though GERD expenditures are outside the top one-third. Cabo Verde, Ethiopia, Ghana, Madagascar, Mauritius, Namibia and Tanzania are all examples of this. Further examination shows that most of these countries have healthy public expenditures on education — generally above 4% of gross domestic product. Impressive performances were turned in by Madagascar, Namibia and Tanzania; each has low expenditures on GERD and public education but still managed satisfactory patent application results.

An observation can be made regarding Table 2: Ample expenditures on education and GERD increase the likelihood of respectable patent application performance. The top half of the patent performers averaged over 5% on education expenditures and 0.5% on GERD. The bottom-half performers averaged 4% on education and less than 0.4% on GERD; as these expenditures trend down, so do patent applications. This supports the belief that investing in education and research and development leads to innovation.

An observation can be made regarding Table 2: Ample expenditures on education and GERD increase the likelihood of respectable patent application performance. The top half of the patent performers averaged over 5% on education expenditures and 0.5% on GERD. The bottom-half performers averaged 4% on education and less than 0.4% on GERD; as these expenditures trend down, so do patent applications. This supports the belief that investing in education and research and development leads to innovation.

Patents and intellectual property are key components of a favorable environment for innovation. They protect knowledge by strengthening intellectual property rights and regulatory regimes at all levels. However, the STI implementation report identifies that the lack of operationalizing the Pan-African Intellectual Property Organization has resulted in a lack of activity in intellectual property management and technology transfer. Rewarding innovation paves the way for future discoveries.

Bright Spots

There are many reasons to be optimistic about the future of innovation on the continent. One example is the Cape Town-based African Institute for Mathematical Sciences’ Next Einstein Initiative. AIMS, established in 2003, is a degree-granting institution with centers in six African countries. Next Einstein Initiative came to be at a TED Talk in 2008 when South African physicist Dr. Neil Turok discussed a dream that the next Einstein will be African. The initiative holds a biennial event, the Next Einstein Forum Global Gathering, to leverage science for human development. The event is driven by the belief that Africa’s contributions to the global scientific community are critical for global progress. The selection of winners for the “Challenge of Invention to Innovation” is made at each Global Gathering; finalists are known as “sciencepreneurs.” One recent invention is a data analytics platform from Rwanda that uses low-power sensor devices to determine optimum levels of fermentation for the tea processing industry. Another is a Nigerian-designed and manufactured rechargeable, trackable, mobile cold box that enables businesses to store and transport temperature-sensitive commodities. Such a box could play a key role in civil and military cold-chain logistics; particularly for temperature-sensitive products such as medicines and vaccines.

In some cases, innovation is made possible by government initiative. A prime example is South Africa’s Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR). The 75-year-old institution supports research in the public and private sectors designed to improve South Africa’s competitiveness on the global stage. The largest research institution of its kind in Africa, it employs more than 2,000 people and gets the majority of its funding through patent royalties and other self-generated mechanisms.

Over the years, key discoveries made possible by the CSIR include: components to lithium batteries, crops genetically engineered to withstand harsh conditions, research on photovoltaic cells for solar power and advances in nanotechnology. The CSIR also is a globally recognized leader in HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis research.

Looking to Space

In 2016, the African Union released two important space-related documents: African Space Policy and African Space Strategy. The strategy has four thematic focus areas: earth observation, navigation and positioning, satellite communications, and space science and astronomy. African countries had satellites in orbit well before these documents were published. In fact, 10 countries have satellites: Algeria, Angola, Egypt, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Morocco, Nigeria, Rwanda and South Africa. Most of these countries helped develop the satellites. None of the satellites has been launched from African soil — yet. Gabon does not have a satellite; however, it does have an Earth-based remote sensing center outside the capital, Libreville. This center, known as AGEOS (Agence Gabonaise d’Etudes et d’Observations Spatiales), operates a large antenna that collects images from satellites and disseminates them to a broad segment of sectors: mining, petroleum, forestry and marine operators. Gabon’s location is key; it is at the center of the Congo basin, which has the second-largest rainforest in the world. The center’s radius of coverage is 2,800 kilometers and covers 17 countries and parts of six others. AGEOS also is working on the development of a weather station.

South Africa is partnering with Australia to build the Square Kilometer Array radio telescope project. Once complete, it will provide astronomers better information about deep space in less time than other telescopes.

The Road Ahead

Africa is an ascending continent for scientific and technological capacities, and there is an abundance of opportunities to explore. The time is right. The talent is there. The opportunity is nearly limitless. What is needed now is investment in terms of education, research facilities and governmental support. With the right mix, the next great scientific discovery of the 21st century might take place on African soil.

Edward Durell, P.E., is an international program specialist at U.S. Africa Command. An engineer by education, he leads outreach efforts to Africa for the Office of Science, Technology and Innovation, managing numerous programs and initiatives. Before his current position, he managed a federal agency program for the development and application of technical specifications and standards.

Edward Durell, P.E., is an international program specialist at U.S. Africa Command. An engineer by education, he leads outreach efforts to Africa for the Office of Science, Technology and Innovation, managing numerous programs and initiatives. Before his current position, he managed a federal agency program for the development and application of technical specifications and standards.