When it comes to building military capacity in Africa, adding aircraft tends to take a back seat because of the expense involved to acquire combat craft, trainers and cargo planes.

Military applications aside, airlift capacity remains a critical need throughout the continent, as much for moving troops to troubled regions as dropping supplies to areas hit by natural disasters.

To address this need, the African Union (AU) has established a cell within its Peace Support Operation Division called the Continental Movement Coordination Center. The center oversees airlift contributed by the continent’s regional economic communities, as well as short-term contract airlift, commercial sealift and land movement for peacekeeping operations. The AU has also compiled a database of continental air assets available through member nations to see where gaps and opportunities exist.

The center’s mandate is to control and coordinate the use of strategic lift capabilities pledged for African Union missions. As a 2015 report by the African Center for Strategic Studies noted, the AU’s highest priority is “the utilization of AU member states’ organic strategic lift assets, with any shortfalls in capability supplemented by contracted commercial assets or partner assistance.”

The first evidence of the center’s potential came in the 2015 Amani Africa II military exercise, when a C-130 transport plane from Nigeria in the Economic Community of West African States region fulfilled an emergency airlift requirement by carrying 100 Soldiers and materiel from the Eastern African Standby Force.

“What this concept is saying is that, as much as we can, we should use the African resources first and mutualize resources for strategic lift, which could be complemented by partner support,” retired Col. Mor Mbow of Senegal said at the time.

Despite widespread agreement on the need for such airlift capacity, actual aircraft remain in short supply. A 2013 book, Military Engagement: Influencing Armed Forces Worldwide to Support Democratic Transitions, Volume II, edited by Dennis Blair, emphasized Africa’s need for more airlift resources: “African militaries must significantly increase capacity in air logistics to address the continent’s environmental and humanitarian crises.

“The famine and drought ravaging the Horn of Africa require urgent intervention, which entails moving tons of foodstuff to remote regions where 9.6 million impoverished people are scattered. Furthermore, in Mozambique, seasonal heavy rainfalls have meant that only air transport is able to intervene and save the lives of desperate people who fail to relocate to higher ground every year. However, most African states lack the assets, resources and training.”

Regional Resources

As Africa weighs strategies to pool resources for airlift capacity, an existing model is worth examining.

The Strategic Airlift Capability (SAC), established in 2008, is based in western Hungary and is an independent, multinational program that provides the capability of transporting equipment and personnel over long distances to its 12 member nations. It owns and operates three Boeing C-17 Globemaster III long-range cargo aircraft.

The SAC nations are NATO members Bulgaria, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Romania, Slovenia and the United States, and NATO Partnership for Peace nations Finland and Sweden. Each participating nation owns a share of the available flight hours of the SAC planes that can be used for missions to serve its national defense, regional commitments and humanitarian relief efforts.

In April 2020, SAC, at the request of the Netherlands, delivered two mobile intensive care units to the island of Sint Maarten in the Caribbean in an emergency response mission. The Daily Herald of the northeast Caribbean reported that the two units housed six intensive-care beds with ventilators and equipment for an additional six intensive-care unit beds in the Dutch Caribbean. This delivery was considered essential for the people of the islands to be able to treat COVID-19 patients.

The SAC concept originated at NATO headquarters in 2006. NATO officials and national representatives envisioned a partnered solution that would “satisfy a need for strategic airlift for member states without the economic resources to field a permanent capability.” SAC got its first plane in July 2009, followed by two more delivered in the following months. By late 2012, the unit was considered fully capable of missions containing air refueling, single-ship airdrop, assault landings, all-weather operations day or night into low- to medium-threat environments, and limited aeromedical evacuation operations.

Airlift on a Budget

In a 2019 study, U.S. Air Force Maj. Ryan McCaughan proposed using reconditioned planes to improve Africa’s airlift capacity. He noted that the United States and other countries assisting African nations with airlift capacity would be better served by offering help on a regional basis, instead of helping individual countries. He said, “Every new crisis in Africa is met with the same daunting task of logistics and air mobility.”

He said that air mobility in Africa must be viewed as a regional resource. He proposed a comprehensive plan in association with, and led by, the African Union. He said African nations needed to take advantage of the “unprecedented availability” of a specific airplane — the C-130 cargo plane.

The Lockheed C-130 Hercules is a four-engine turboprop military transport plane that was first produced in 1955, and updated versions are still being made. It was designed to accommodate the conditions of the Korean War, with the United States needing a versatile transport plane that could airlift troops over medium distances and land on short, basic airfields.

About 70 countries have acquired C-130s over the years. More than 2,500 of the planes have been produced. There are more than 40 variations on the standard C-130. Forbes magazine has predicted that the C-130 likely will become the first military aircraft in history to stay in continuous service for 100 years.

The United States has worked with individual African nations to improve their airlift capacities, specifically with the C-130. In 2018, the U.S. donated a refurbished C-130 to Ethiopia. DefenceWeb reported that U.S. Embassy officials said the plane would “further enhance Ethiopia’s capacity to play a vital role in regional peacekeeping missions, enabling Ethiopia to move humanitarian supplies where they are needed in a timely manner and protect the lives of civilians in conflict areas.”

In January 2020, the U.S. handed over a new C-130 Hercules hangar to the Nigerien Air Force at Air Base 201 near Agadez. “Niger will be receiving ex-U.S. C-130 aircraft later this year,” defenceWeb reported.

The U.S. paid for the construction of the hangar, which was built within a year by international workers and about 90 Agadez residents. The hangar includes an engine maintenance room, supply storage, training area, and battery and tool rooms.

The hangar ultimately will shelter up to two C-130 transport aircraft, recently purchased by the Nigerien Air Force from the United States, defenceWeb reported.

The Best Choice

In his study, McCaughan concluded that the C-130 seems to be the best tool for improved airlift capacity in Africa in part because the U.S. already has chosen it for that purpose.

“Few would disagree that, in terms of capability provided, the C-130 is right for Africa,” McCaughan wrote. “Primarily in terms of cargo capacity, flight time, and unimproved surface landing capability, this asset provides the answer for a region so frequently plagued by war and famine enhanced by what has been dubbed the ‘tyranny of distance.’ With a range of greater than 1,500 nautical miles, the capacity to carry up to 42,000 pounds of cargo, and ability to be reconfigured to adapt to a variety of mission sets, this is the perfect aircraft for a continent with limited staging locations and a lack of surveyed landing zones which may necessitate a range of 1,000 miles before refueling can occur.”

The C-130H’s annual maintenance and sustainment costs of $5 million to $6 million are relatively low compared to similar aircraft, McCaughan argued.

The Excess Defense Article program is designed so that a country or region takes ownership of an asset such as an airplane on an “as is” basis by assuming responsibility for all costs of moving, repairing and maintaining it.

McCaughan said the African Union should use SAC as a model for its own regional airlift support capacity. As with SAC in Hungary, the AU should pick a “framework nation” that would take responsibility for the cost of restoring and maintaining donated C-130s in a region. The AU would develop a funding model to support part of the operational and maintenance costs of the aircraft. He said one model could use a flight-hour sharing plan negotiated among the host nation, the AU and other partners in Africa.

Individual countries in Sub-Saharan Africa have struggled financially to maintain their transport planes. McCaughan concluded that a new way of managing military transport fleets is the only answer: “Until regional, governmental partners with similar interests unite contractually with one another as well as industry capable of conducting high-level maintenance, the cycle will not be broken and air mobility in Sub-Saharan Africa will remain elusive.”

The Cost of Returning a Plane to Service

Lockheed Martin has produced C-130 transport planes since 1955. ADF interviewed Dennys Plessas, vice president of Lockheed Martin International Business Development-Africa, Greece, Italy and Latin America, about the practice of returning out-of-service C-130s to the skies. The questions and answers were exchanged via email and edited for length.

ADF: Recognizing that no two vintage planes are alike, how much does it cost to return a well-maintained vintage C-130 to service?

Plessas: Just because an aircraft is well-maintained does not mean that it is either compliant to fly in worldwide airspace or is not approaching a service-life limit that requires a part as large as the wing to be replaced. In the case of 40-plus-year-old C-130s, the price of a depot overhaul just to return the aircraft to service can exceed the value of the airplane.

The most recent C-130s to be returned to service were part of the U.S. government Excess Defense Article (EDA) program. The aircraft were given the appropriate overhaul in a U.S. government depot in order to be delivered.

ADF: What’s the value of a good used C-130?

ADF: What’s the value of a good used C-130?

Plessas: In recent years, we have seen the values of used C-130s range from hundreds of thousands of dollars for an airplane cannibalized for parts to the mid-$10 million to $20 million range for an approximately 35-year-old C-130H with a new glass cockpit.

ADF: What is the annual cost of maintaining a C-130 that is used regularly? Former Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Norton Schwartz told Congress in 2012 it cost $10,400 per hour to fly the C-130. Is that still an accurate figure?

Plessas: The cost of maintaining a C-130 is determined by several factors, to include:

- How many hours the aircraft is flown each year.

- The availability rate that is demanded by that operator.

- Fleet size.

Whether the aircraft is maintained by a government facility or through a commercial service center.

The cost per flight hour is broken into fixed costs and variable costs. Fixed costs are dominated by maintenance and are usually spread across a fleet. Large fleets usually have lower fixed costs per aircraft because of the economy of scale as compared to a small fleet. The variable costs are consumables such as fuel and crew salary.

One of the biggest fixed-cost drivers is the effect of availability rate on maintenance. New C-130s when delivered have availability rates upwards of 90%. After 40 years of flying, we see an aircraft’s availability rate drop to between 50% and 55%. As an aircraft ages, it requires more inspections and more spare parts, while operators also have to factor in parts obsolescence. It is possible to regain some of the availability rate, but that requires a large influx of money.

ADF: What is involved in maintaining a C-130?

Plessas: C-130s are either maintained by government-owned depots, by government-contracted commercial entities (most commonly airlines) or Lockheed Martin-approved service centers. There are 17 Hercules Service Centers located on six continents that can support the maintenance checks along with aircraft depot level maintenance modification and overhaul support. Denel in South Africa is the only Hercules Service Center on the continent and has experience maintaining the South African Air Force’s C-130BZ fleet.

ADF: At what point is a well-maintained vintage C-130 not worth keeping in service or putting back in service? Is the age of the plane the chief factor?

Plessas: The C-130 has no life limit in terms of years, but there are considerations to be made when evaluating keeping a C-130 in or out of service.

Let’s look at the C-130H model as an example. C-130Hs were built from 1964 to 1996. The economic service life of a C-130H in service with a major military operator is approximately 40 years and is dependent on how the aircraft was flown and maintained by that operator.

Service limits exist for the C-130H aircraft structure/structural components in terms of hours and number of events (i.e., number of landings). A “service limit,” “service year limit” or “service life limit” should not be confused with the aircraft economic service life. Factors other than structural limits should be considered when evaluating economic service life such as the economics of operating an older aircraft and the decline in availability rate due to additional maintenance.

As C-130Hs age, their availability rates decrease. Many military operators report availability rates of 50% with 35- to 40-year-old C-130Hs. Routine and unforecasted maintenance due to age significantly impact availability rates. Unanticipated support concerns increase the time the aircraft remains in depot as well as requiring more labor, parts and engineering support. These all translate to less availability and more cost.

ADF: There are varying figures as to how many C-130s are still operating in Sub-Saharan Africa. Do you have any estimates?

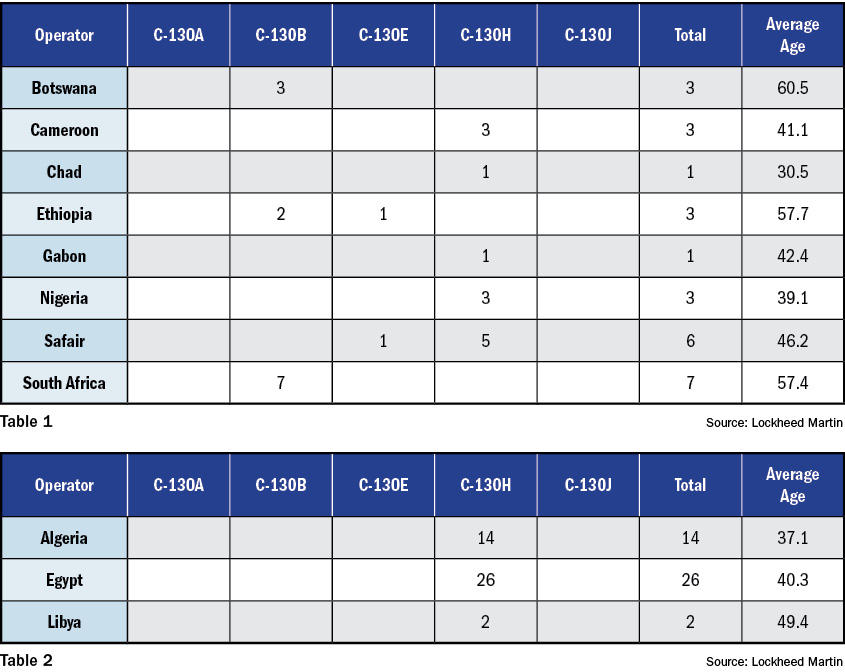

Plessas: Based on the Lockheed Martin database at this time, the breakdown for C-130 Operators in Sub-Saharan Africa is: (Table 1).

Based on the Lockheed Martin database at this time, the breakdown for North Africa is: (Table 2).

The following countries replaced their C-130Hs with C-130Js at these ages:

- Italy – 30 years

- Denmark – 29 years

- Norway – 39 years

- United Kingdom – 35 years

- Australia – 34 years

- Canada – 35 years

ADF: What kind of facilities would regional groups in Africa have to build to house and maintain one or two C-130s?

Plessas: Operators typically need a hangar large enough to house a C-130. Most hangars, due to economy of scale, are built to house two or more aircraft because the facilities not only house the aircraft for maintenance, but also contain facilities for aircraft painting, support shops for technicians, a technical library, storage area for aircraft parts and office space.

ADF: A 2019 study recommended that such regional facilities in Africa have at least three C-130 planes. Is there an economy of scale in maintaining three or more such craft?

Plessas: There is an economy of scale. There is a minimum set of infrastructure for one C-130. Expanding to three C-130s does not triple the infrastructure. In a one-aircraft fleet the entire fixed infrastructure cost is borne in the cost per flying hour. That cost is divided in a three-aircraft fleet.

Lockheed Martin’s Operational Analysis team has consistently recommended a minimum of three aircraft in a fleet to be operationally effective. In general, one aircraft is usually in a maintenance action. The reality is only two aircraft are available for tasking. Training missions will impact the tasking level of the two aircraft. q

Nearly 40 variants of the C-130 Hercules were manufactured and they were sold under the name L-100 to nearly 60 of the world countries. As for the service of C-130 Hercules with US military, it started back in 1956 and aback in 2007, the C-130 Hercules became the 5th ever aircraft to have completed the service of 50 years with the US military.