Sahel-Based Extremist Groups Shatter the Calm of Burkina Faso

ADF STAFF

Burkina Faso’s Splendid Hotel promotes itself to international visitors by listing the amenities many have come to expect. Room service. A front desk staffed 24 hours a day. Proximity to restaurants and local attractions. Free Wifi. Business travelers, diplomats and vacationers all have made the Splendid their temporary home when visiting the capital, Ouagadougou.

Its rooms offered a natural sense of calm and safety. That was the feeling that a half-dozen al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb militants sought to shatter in January 2016 when they laid siege to the hotel after attacking the Cappuccino café, which was packed with 100 customers across the street.

Attackers wearing turbans and speaking a nonnative language trickled into the hotel throughout the day on Friday, January 15, 2016, and mixed with guests. More joined them as darkness settled in, CNN reported. Finally, the attackers began their assault and took hostages.

At least 29 people were killed, and dozens were injured. One survivor told the BBC of how attackers refused to be fooled by victims. “They started shooting, shooting, and everybody lay down on the ground,” said a woman, who escaped with her younger sister. “As soon as you lifted your head, they would shoot straightaway, so you had to pretend to be dead. And they even came to touch our feet to check if we were alive. As soon as you were alive, they would shoot at you.”

At least 29 people were killed, and dozens were injured. One survivor told the BBC of how attackers refused to be fooled by victims. “They started shooting, shooting, and everybody lay down on the ground,” said a woman, who escaped with her younger sister. “As soon as you lifted your head, they would shoot straightaway, so you had to pretend to be dead. And they even came to touch our feet to check if we were alive. As soon as you were alive, they would shoot at you.”

Local and French security forces surrounded the Splendid early on January 16, 2016, before storming it, rescuing 176 hostages, Burkinabé Security Minister Simon Compoare told the BBC. Among those killed, in addition to four assailants, were five Burkinabé citizens, two French nationals, two Swiss citizens, six Canadians, a Dutch citizen and an American missionary.

Terror had come to Burkina Faso, long a place of relative calm. Now instability and violence that plagued Mali, and to a lesser extent, Niger, was seeping across the border, challenging a government with political will but little capacity to face the problem.

VIOLENCE IN THE LAND OF THE ‘UPRIGHT’

Burkina Faso, formerly the Republic of Upper Volta, embedded a desire for national unity into its new name. In 1984, the country’s new name combined words from three indigenous languages to represent the nation and its people. Burkina, which is Mossi for “upright,” and Faso, which is Dioula for “fatherland” or “country,” combined to denote the nation as “the land of upright people.” Burkinabé refers to a citizen, adding the suffix “bé” from the Fulani Fulfulde dialect to Burkina, to mean a “person with uprightness.”

Then-President Thomas Sankara used the new name to foster national cohesion and identity, said Dr. Daniel Eizenga, a research fellow with the Africa Center for Strategic Studies (ACSS). “That’s always been really strong in Burkina Faso, this recognition of the differences and diversity, but as a cohesive unit,” he said. In many ways, that sense of national unity has helped the nation despite increased violence in recent years.

Back in 2014, hundreds of thousands of protesters took to the streets of Ouagadougou to protest then-President Blaise Compaoré’s attempt to amend the constitution to extend his rule, which started when he overthrew Sankara in a 1987 coup. This “Popular Insurrection,” as it came to be known, uprooted Compaoré, forcing his resignation and exile to Côte d’Ivoire. Thus began a yearlong transition to a democratically elected civilian government.

Citizens voted in free and fair elections in November 2015, electing current President Roch Marc Christian Kaoboré and giving his party a plurality in the National Assembly. The new government was installed in January 2016. Then tragedy struck at Cappuccino café and the Splendid Hotel.

This put Kaoboré’s government on the back foot immediately after a peaceful government transition. “Since January 2016, the government has just grappled with trying to figure out what’s going on, why do we see an increase in insecurity, what militant Islamist groups are active in the territory, and they’ve struggled to address those challenges,” Eizenga told ADF. “So now here we are in 2019, three years later, and we’ve seen just a steady increase — a steady uptick — in that insecurity.”

BURKINA FASO’S FACE OF TERROR

The hotel and café attacks began a surge of violence in Burkina Faso that persisted deep into 2019. In 2018, 137 violent events killed 149 people. In 2019, extremist Islamists had killed 324 people in 191 attacks by midyear, according to a July 2019 paper by Pauline Le Roux, visiting assistant research fellow with the ACSS.

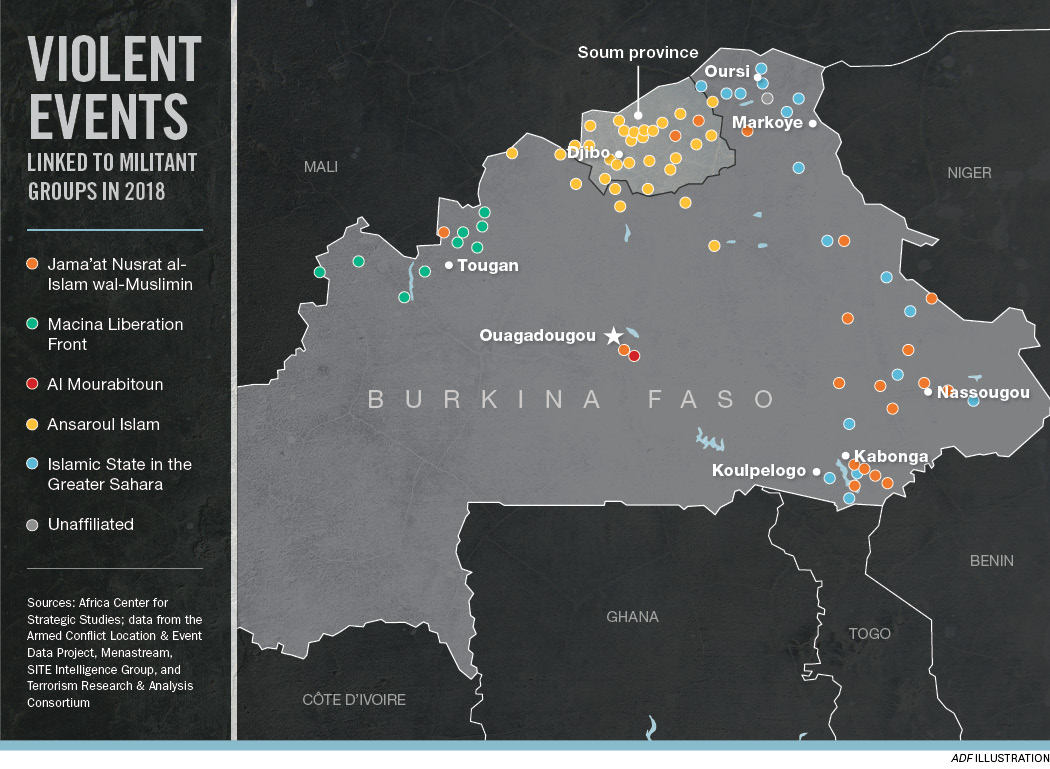

Three groups have been responsible for most attacks, but one — Ansaroul Islam — has led the way in destabilizing Burkina Faso’s north. Between 2016 and 2018, more than half of all militant Islamist attacks in the country came at the hands of Ansaroul Islam, mostly clustered around Djibo, the capital of Soum province. In 2018, the group led 64 attacks that killed 48 people. More than half of its attacks — 55% — targeted civilians, which ranks Ansaroul Islam first among all other militant groups on the continent except for one operating in northern Mozambique, Le Roux wrote. More than 100,000 people fled their homes, and 352 schools closed in Soum.

Those attacks on civilians, coupled with the 2017 death of the group’s founder, Ibrahim Malam Dicko, a Fulani imam, probably led to the group’s decline. By mid-2019, only 16 attacks and seven deaths could be attributed to Ansaroul Islam, and the group ceased to be a major player in the nation’s extremist threat.

Although primarily an ethnic Fulani and Muslim group, Ansaroul Islam lacks some of the grander designs for conquest and territorial control shared by extremist groups operating in central Mali. For example, the Macina Liberation Front (FLM) espoused a desire to reestablish the old theocratic Macina Empire in central Mali.

Eizenga said Ansaroul Islam attracted a lot of attention because it was Burkina Faso’s first homegrown extremist group. The fear was that it would metastasize and spawn breakaway groups. That did not happen. In fact, the group never won significant local support. It primarily was a band of disgruntled young men who took up arms because they couldn’t find jobs. It seemed that the group attacked civilians because it lacked popular support, not the reverse, he said.

The nation’s long-embedded social values worked to its advantage. Its social structures provide local processes for resolving conflict and keeping the peace. So why has violence come to Burkina Faso?

EXPANDING THE BATTLEFIELD

No group seeks to establish a caliphate or breakaway state in Burkina Faso. Instead, the violence spreading into the country likely is due to two factors. First, military crackdowns in Mali and Niger by French forces in Operation Barkhane, the G5 Sahel Joint Force and national militaries have pressured extremist groups. As those groups seek safe havens, they exploit borders between Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, part of a region historically known as the Liptako-Gourma. Those safe havens include northern and eastern Burkina Faso.

Eizenga explained that populations in the three countries are “highly interconnected,” so national borders don’t necessarily distinguish people or influence their movements. “So what we’re really talking about here is a regional problem for the Malian state, the Burkinabé state and the Nigerien state,” he said. Pastoralists move freely through the region, and that regular migration complicates security efforts. To blame the violence solely on Malian unrest misses the point that this was a regional problem from the beginning, Eizenga told ADF.

Second, the violence in Burkina Faso is less about extremists trying to fulfill a larger ideological or political goal and more about a tactical decision to “expand the battlefield,” he said.

In addition to Ansaroul Islam, the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara and FLM have been most active in Burkina Faso, according to Le Roux’s paper. Eizenga said reports tell of attackers riding into Burkinabé communities on motorbikes, burning buildings and killing a few people. This tactic keeps Burkinabé and other security forces on the defensive because it forces them to spread manpower and materiel across a wider area, thus diluting effectiveness and response time.

Spreading into new areas also opens new revenue sources. The move into eastern Burkina Faso has some observers concerned that the threat could expand to Benin and Togo. In May 2019, French forces freed two French tourists, one American and a South Korean in Benin, according to The Washington Post. Terrorists had killed their guide, and two French Soldiers died in the rescue. Criminal gangs could kidnap others and transfer them to extremists for money.

Also, Eizenga explained that pastoral communities need to get cattle to markets, and that requires moving toward the coast. Extremists could exploit or attempt to control such movements through extortion. Furthermore, movement into coastal West Africa would give militants access to “large-scale attacks on soft targets,” such as the March 2016 Grand Bassam beach resort attack in Côte d’Ivoire that killed 19 people.

BURKINA FASO’S WAY FORWARD

Burkina Faso’s social structure gives it an advantage when combating extremists. The lack of local support for such groups may keep them from taking root in the country. However, the low capacity and resources of regional security forces is a continuing challenge.

The government, Eizenga said, has the political will to act. Officials have the sense of urgency and desire to address the threat. “It really is a question of capacity,” he said. “So sustained, long-term military presence is going to be crucial.”

Establishing security would enable improved economic development, which would further strengthen national resilience. But security must come first, and Burkina Faso won’t be able to handle that alone. The international community will have to help. Hundreds of thousands are displaced, and as of fall 2019, the country was entering its dry season, which could lead to food scarcity.

“We’re at this really delicate moment where, unless the Burkinabé government has the support of the international community and we see some mobilization on a humanitarian front and on a security front, I don’t know that they’ll be able to get past that short-term period,” Eizenga said.

If the G5 Sahel Joint Force could operate at full capacity across the Sahel region, it might be able to provide the sustained security necessary for the mid- and long term. But that, too, likely will require increased international support. Barkhane and the G5 Sahel have had some successes, but as they do, militants attack other areas to expand the battlefield. “What has been missing so far is the ability to sustain a military presence in a broad enough space that it fully disrupts the ability of these groups to operate,” Eizenga said.

Despite this, Burkina Faso’s government has addressed insecurity. It has declared a state of emergency in about a third of the nation and has increased its military presence in those areas. It has launched military operations in the north and east with some success. But an August 2019 extremist attack on an Army unit in Koutougou, Soum province, killed about two dozen Soldiers and wounded several others. That happened because Burkina Faso is trying to restore security in a complex and challenging environment, Eizenga said. With increased support, they could turn the tide.

“There’s not a reason to lose all hope in Burkina Faso yet.”

Comments are closed.