ADF STAFF

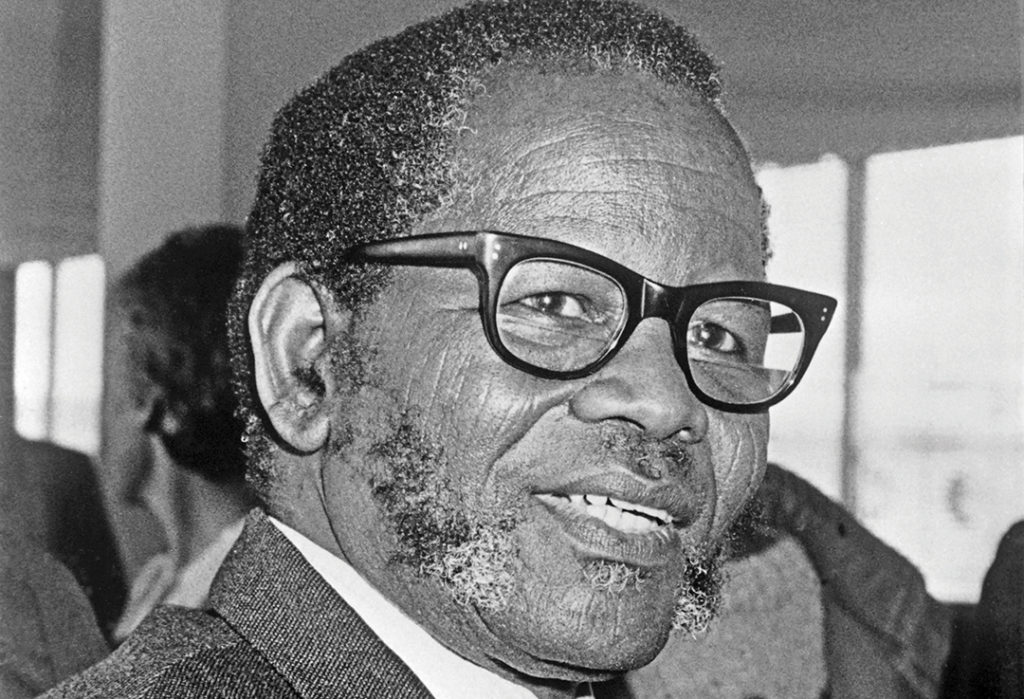

The world recognizes Nelson Mandela as the father of post-apartheid South Africa, but he always acknowledged he had help. One of his key partners was Oliver Tambo.

For nearly three decades, the two men led the fight against apartheid from distinct places — Mandela from a prison cell and Tambo from exile. Mandela described Tambo as “my partner, my comrade, my friend and my colleague.”

Tambo was born in 1917 to peasant farmers. A good student, he attended mission schools and won a scholarship to Fort Hare University, which had become a center of political activism. Mandela, who also attended the school, said, “For young black South Africans like myself, it was Oxford and Cambridge, Harvard and Yale, all rolled into one.”

Tambo became an activist, leading a protest after an attack on a black female dining-hall employee by a white male student went unpunished. He led another protest over unfair restrictions on the use of a campus tennis court. In 1944, Tambo, Mandela and others formed the Youth League of the African National Congress (ANC), aimed at getting the parent organization to become more aggressive in ending white minority rule.

The youth league got results. In 1952, a year after Mandela and Tambo started South Africa’s first black law firm, the ANC adopted a league plan that called for civil actions, including strikes, boycotts, protests and defiance of apartheid laws. Four years later, Tambo and Mandela were charged with treason but found not guilty.

Everything changed in 1960 when police killed 69 demonstrators and wounded 181 more in what came to be known as the Sharpeville Massacre. It was the turning point for Tambo and others, who decided that nonviolent protests were “meaningless.” The ANC was banned days later, and its leaders became enemies of the state. They formed a military group called Umkhonto we Sizwe, or Spear of the Nation.

At that time, Tambo was sent out of the country to drum up support for the underground movement. It was his job to tell the rest of the world about the ugliness of apartheid. He was tasked with obtaining weapons, organizing international sanctions, and building an army in South Africa’s neighboring countries. He would remain in exile for more than 30 years.

In 1962, Mandela was arrested after attacks on government buildings and was sentenced to life in prison. A year later, the Soviet Union agreed to help arm the rebellion. In 1967, the exiled Tambo was named president of the ANC.

As The New York Times later reported, by 1981 “attacks on police stations, pass-records offices and oil refineries were occurring on an average of one every 53 hours.” Tambo urged black South Africans to make their townships “ungovernable.”

But even in war, Tambo demanded honor. He committed his Soldiers and the ANC to follow the Geneva Convention and its rules for human rights. He addressed gender inequalities.

Because of their isolated positions as leaders of the revolution, Mandela and Tambo had to rely heavily on the indigenous African consensus system of decision-making. They required their followers to think independently, and when decisions were made, they usually included some of the opinions of all participants.

Tambo suffered two strokes while in exile, and when he returned to his home country in late 1990, he was a frail man. The next year, Mandela replaced him as president of the ANC. Tambo died in 1993 at age 75.

His legacy includes Africa’s busiest airport, O.R. Tambo International, which handles 19 million passengers a year. But perhaps his lifelong vision of South Africa is his finest tribute. He said that a free South Africa would welcome all its citizens, black and white: “South Africa belongs to all who live in it.”