ADF STAFF

A visitor to Lusaka, Zambia’s capital city, doesn’t need to go far to see China’s impact.

Passengers arrive at the glass-walled, $100 million Kenneth Kaunda International Airport. They drive past construction crews building the $1.2 billion Lusaka-Ndola carriageway. Football fans can watch a match at the 60,000-person, $94 million Heroes National Stadium. And when lights are switched on, the power is generated by the Kariba Dam and hydropower station on the Zambezi River.

All of these projects were financed through Chinese loans and built by Chinese contractors.

The projects are impossible to miss. What is harder to see is their impact on the nation’s economy. Zambia’s external debt is estimated at $11.2 billion. About half of that is owed to China. Every year, 40% to 50% of Zambia’s domestic revenue goes toward debt service, which means after public sector employees are paid, a sliver of the budget is left to fund needs like education and health care.

When observers look closer they see cracks in the façade. In some cases the quality of the construction is poor. In 2011, the Chinese-built Lusaka-Chirundu Road crumbled and was partially washed away after a heavy rain. In other cases, like Zambia’s two glitzy sports stadiums, the projects have been dubbed “white elephants.” This means they look impressive but are not practical and don’t generate much revenue.

Finally, there is the opacity of the China-Zambia contracts. Few know the terms of the deals or who profits from them.

“Chinese loans often don’t even go to Zambian accounts,” former Zambian Minister of Information and Broadcasting Chishimba Kambwili told Deutsche Welle. “They choose the contractor from China, the contractor is paid in China, but it reflects in our books as a loan from China.”

Although Zambia’s debt crisis is among the continent’s most serious, other African countries are paying close attention. They realize that the pitfalls of large foreign debt might be waiting for them if they don’t change course.

“The rest of African nations can learn from the Zambia-China relations,” Zambian scholar Emmanuel Matambo, part of the Southern Voices Network for Peacebuilding at the Woodrow Wilson Center, told ADF. “The fact is that China’s unqualified disbursement of debt to weak African economies could have massive implications on African democracy.”

Modern Chinese political and business ties to Africa date back to the 1960s. At the time, Chinese Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong sought to deepen ties with several African countries due to a shared anti-colonial position. Among the first major infrastructure projects was the Tanzam Railway connecting Zambia with the Tanzanian coast.

Since the early 2000s, many African countries, particularly those with mineral wealth, have chosen to make deals with Chinese state-owned enterprises to build roads, bridges, ports, airports and other infrastructure.

The appeal of Chinese debt is obvious. The loans have few strings attached to them; they don’t require transparency, economic reforms or human rights standards. In some well-known cases, high-ranking officials received payoffs in exchange for rubber-stamping the loans.

Leaders of African nations often insist that they have no choice but to partner with China since it is typically the only lender offering to finance a project. A study by the Kiel Institute for the World Economy found that China lent more money to Africa than did the World Bank, International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Club of Paris countries combined.

“When people complain about Chinese loans, it’s not as if most African countries have a plethora of options,” Gyude Moore, Liberia’s former minister of public works and a senior fellow at the Center for Global Development, told Bloomberg.

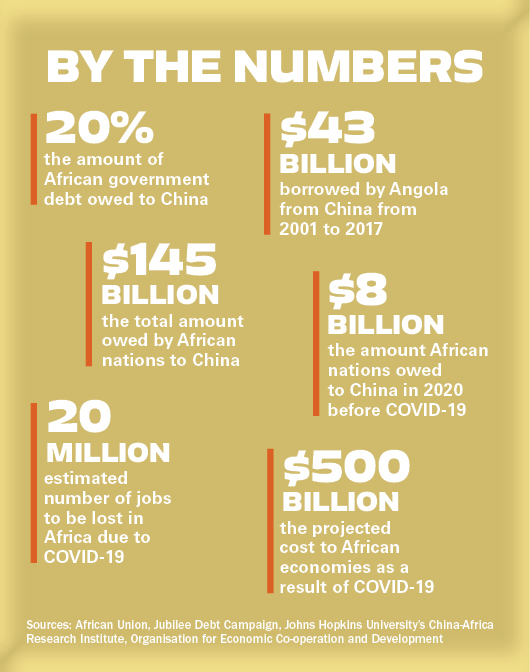

Today, China is the largest creditor to the African continent and is owed about $145 billion. According to Johns Hopkins University’s China-Africa Research Institute, Angola received the most in Chinese loans between 2000 and 2017 at $43 billion, followed by Ethiopia at $13.8 billion, Kenya at $8.9 billion and Zambia at $8.6 billion.

COVID-19 and Debt Relief

The COVID-19 pandemic brought the world economy to a near standstill. African economies, many of which rely heavily on mineral extraction, tourism and agriculture, have been hit particularly hard.

According to the IMF, Sub-Saharan African economies will shrink by at least 3% in 2020. Before the pandemic, they were forecast to grow by several percentage points.

In light of this global crisis, debt payments that once felt manageable have become overwhelming. African nations owed China about $8 billion in payments in 2020, of which about $3 billion is interest. Several large countries spend more on interest payments for debt than they do on health care.

“Although the COVID-19 pandemic will pass, its consequences for people, economies and our planet will be with us for a long time to come,” South African President Cyril Ramaphosa said during a virtual China-Africa summit.

The crisis has led to a chorus of calls for China and other lender nations to offer debt relief to Africa. There has been some progress. In April 2020, the G-20 countries, of which China is a part, pledged to suspend debt repayments from 73 of the world’s poorest countries for at least eight months.

China also has made concessions. In June 2020 it agreed to forgive interest-free loans made to African countries. However, observers point out that the interest-free loans represent a small fraction of China’s total portfolio of loans to Africa — only 5%, according to the China-Africa Research Institute.

Despite public shows of goodwill and a virtual summit with African leaders in July 2020, China has resisted calls for additional debt relief. Observers say the country prefers one-on-one negotiations about debt restructuring over any sort of broad relief plan.

“The Chinese attitude towards that, to begin with, is quite resistant,” Yun Sun, director of the China program at the Stimson Center, told Voice of America. “It doesn’t mean that China will not engage in, for example, debt renegotiation or debt restructuring or even postponement to owe for a longer grace period for the African countries to pay back their debt. But I think a blanket debt forgiveness is not in the cards.”

A Voice from the Past

In a 1987 speech at the Organization of African Unity in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Burkinabe President Thomas Sankara urged leaders to form a “united front against debt.” Sankara believed debt was one of the quickest ways for relatively young nations to lose sovereignty. “Debt is a cleverly managed reconquest of Africa aiming at subjugating its growth and development through foreign rules,” he told the crowd three months before his assassination.

In the midst of the COVID-19 crisis, many nations around the world are reexamining Sankara’s warning. As lockdowns end and economies reopen, leaders will try to balance the need for growth and development with the urgent requirement to protect the health and welfare of citizens. The lessons learned by Zambia and other African countries show that foreign debt is a short-term answer that can carry hidden costs.

Debt as a National Security Threat

ADF STAFF

Crushing foreign debt has implications in nearly every facet of national life. And although the economy is affected most directly, a nation’s debt burden and foreign-built infrastructure projects also can jeopardize security.

Critical national infrastructure: When foreign entities lend money to finance projects such as ports, railroads or airports, the infrastructure itself often is used as collateral for the loan. In the case of China, the threat of taking back the property looms large. Several prominent projects, such as the Port of Djibouti and Kenya’s Port of Mombasa and Standard Gauge Railway, are reportedly at risk of being seized due to mounting debt. China has done this in other parts of the world, including Sri Lanka, where it took control of a port. Foreign control of critical infrastructure threatens security in a range of ways such as limiting a country’s ability to position military assets and compromising its oversight of people and goods entering the country.

Espionage: Chinese contractors with close ties to the Chinese Communist Party have a history of using development projects to collect information. In 2018, China was accused of installing listening devices and programs to secretly back up computer servers at the African Union headquarters in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. A report by The Heritage Foundation found that Chinese companies have built 186 government buildings and 14 sensitive intragovernmental telecommunications networks in Africa. This makes spying easy. “The Chinese government has a long history of all types of surveillance and espionage globally,” Joshua Meservey, senior policy analyst for Africa at The Heritage Foundation, told Voice of America. “So we know this is the sort of thing they want to do, the sort of thing they have the capacity to do.”

Natural resources: Chinese loans are sometimes backed by guarantees of access to commodities. This means that if a nation is unable to pay in cash, China can recoup its money by taking the debtor country’s natural resources. In Africa, one-quarter of all loans are backed by resources such as oil, copper, bauxite and cocoa, according to the consulting firm Deloitte. Safeguarding natural resources is closely linked to national security. This is especially true of mineral and oil wealth, which often are used to finance military expenditures.

Instability: Debt crises lead to unemployment, inflation, drastic cuts in government spending and shortages of consumer goods. History shows that national security is closely linked to economic security. “From Latin America’s lost decade in the 1980s to the more recent Greek crisis, there are plenty of painful reminders of what happens when countries cannot service their debts,” wrote Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz and United Nations Development Programme Senior Advisor Hamid Rashid. “A global debt crisis today will push millions of people into unemployment and fuel instability and violence around the world.”