As the African Union Sifts Through Lessons and Challenges, New Logistics Approaches Are Born

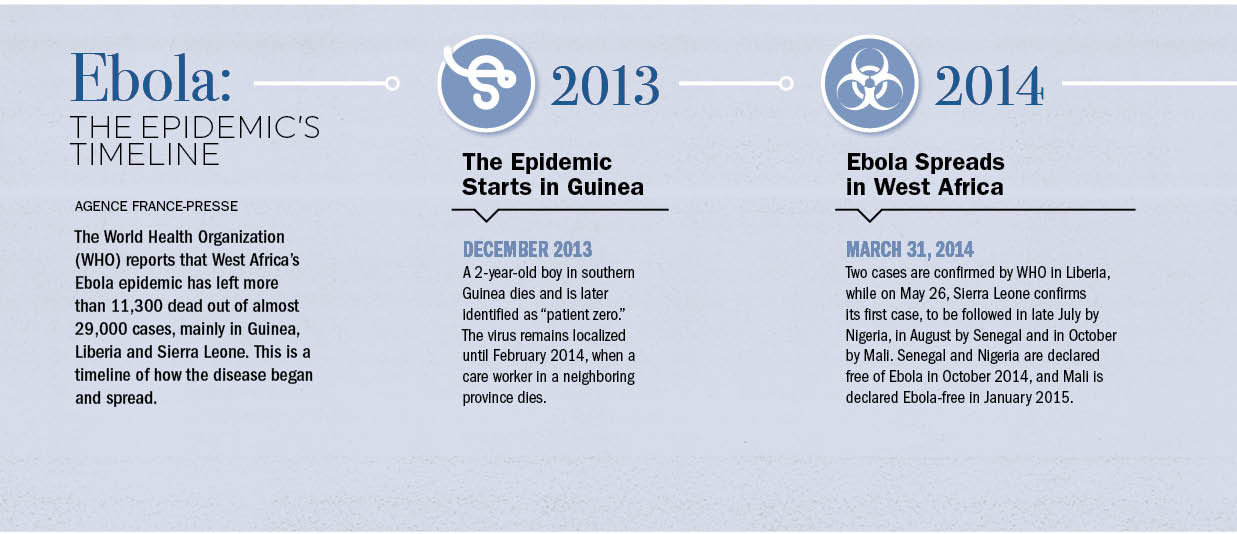

More than two years after Ebola began its deadly march through Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, killing more than 11,300 people, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced what seemed like a miracle: The epidemic was over.

January 14, 2016, marked 42 days since the last Ebola cases in Liberia had tested negative. Liberia’s last two patients — the father and younger brother of a 15-year-old victim — were discharged from a hospital on December 3, 2015.

![Dr. Benjamin Djoudalbaye, senior health officer with the African Union Commission [PHOTO COURTESY OF DR. BENJAMIN DJOUDALBAYE]](https://adf-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/DrDjoudalbaye-150x150.jpg)

By January 21, Sierra Leone had its second confirmed case. The 38-year-old woman had taken care of her niece, 22-year-old Marie Jalloh, who died of Ebola on January 12, a WHO spokesman told Agence France-Presse. Officials were expecting more cases from among those who washed Jalloh’s body during traditional burial preparations. The practice has been identified as a primary mode for the disease’s spread.

“It is disappointing, of course, considering the fact that we have gone for over 100 days since we last recorded a case,” Sierra Leone’s Health Ministry spokesman Sidi Yahya Tunis told AFP on January 21.

Observers were heartened that the patient had been identified as a “high-risk contact” but questioned why she was treated as an outpatient and allowed to come into contact with as many as 27 people. The lessons from the outbreak, it would appear, are still being learned and applied.

Ebola’s persistence in the face of international efforts makes one thing clear: Ebola will continue in Africa. Another outbreak is certain. Sometime. Somewhere. And it is not the continent’s only pandemic threat. There is the Marburg virus, pandemic influenza and cholera, among others.

THE AU RAMPS UP ITS RESPONSE

Ebola mobilized worldwide aid, support and personnel. The United Nations set up the U.N. Mission for Emergency Ebola Response (UNMEER), the U.N.’s first emergency health mission. WHO and Doctors Without Borders mobilized, along with a U.S. military force, Operation United Assistance, which deployed nearly 3,000 Soldiers to West Africa. The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) also responded.

Among them, working hand in hand with all stakeholders, was the African Union, which deployed 855 people to Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone in an effort known as the African Union Support to Ebola Outbreak in West Africa (ASEOWA). The mission, which officially ended December 31, 2015, now is taking stock of logistical challenges and successes, all while preparing for Africa’s next disease outbreak.

![A worker hangs protective rubber boots on wooden racks in December 2014 at the AU-run Magbenteh Ebola Treatment Centre in Sierra Leone. [UNMEER/MARTINE PERRET]](https://adf-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/15640649154_2321bc275b_o.jpg)

Standing up the ASEOWA response was not easy, said Dr. Benjamin Djoudalbaye, senior health officer with the AU Commission. Djoudalbaye, a Chadian doctor based in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, served as chief operating officer of ASEOWA until March 2015, when he took over as head of mission support. Later he became head of mission, replacing Ugandan Maj. Gen. Julius Oketta.

As the mission ramped up, officials dealt with three major logistical problems: air transportation, accommodations for personnel and ground transportation in the affected countries.

“The number one challenge was on the transportation,” Djoudalbaye said. Planners determined early on that the greatest need was for human resources. “When we had mobilized the people, how do we get them down there?”

Some countries had enacted travel bans to the affected region, so the AU flew people in via charter flights through Morocco. Officials chartered flights through Egyptian Airlines, Asky Airlines and Kenya Airways to get people into West Africa.

“Now, when you arrive on the ground there, the challenge number two is accommodation. There were not enough hotels for our people because you have to put everybody in a secure space where they are safe. Also, when you have the accommodation now, the price went to double, triple — it was just very expensive to accommodate our people there.” Rather than keep people in hotels, ASEOWA approached civilians who had extra houses who would rent them out to workers.

The third major challenge centered on transportation on the ground once ASEOWA personnel arrived in West Africa. Workers needed cars and SUVs to perform the painstaking work of “contact tracing,” which is when health workers track down every person an Ebola patient has interacted with for evaluation and possible quarantine or treatment. The lengthy practice is central to halting the disease’s spread. Vehicle availability was an issue, and prices shot up with the sudden demand, Djoudalbaye said. In May 2015, UNMEER supplied some cars to ASEOWA.

![Staffers don protective gear at the Magbenteh Ebola Treatment Centre in Sierra Leone. [UNMEER/MARTINE PERRET]](https://adf-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/15640651564_6dab71f190_o.jpg)

From September to November 2014, procurement issues were slow and difficult. But then the chairman of the AU Commission signed a waiver, allowing ASEOWA to speed up procurement despite the AU’s strict procurement policy. It eased the ability to get supplies as well as recruit people. Djoudalbaye agreed that an outbreak is no time for stifling bureaucracy.

LOOKING AHEAD TO FUTURE OUTBREAKS

The AU and WHO are moving forward with plans to prepare for the next, inevitable outbreak, whatever, whenever and wherever it may be. The possibilities are many. The WHO indicates that about 100 “acute public health events” are called in to its African Regional Office each year. The most frequently reported outbreaks are cholera, dengue, measles, meningitis, plague and viral hemorrhagic fevers, such as Ebola.

The WHO, “recognizing the critical role and importance of logistics in outbreak preparedness and response,” in 2015 established the “Regional Logistics Strategic Plan 2015-2018” in collaboration with other partners, including USAID and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Over the past years, the importance of logistics during outbreak preparedness and response has been critical in ensuring that essential supplies and reagents are prepositioned and deployed rapidly to the field in support of outbreak operations,” the WHO plan states. “This importance is emphasized in the WHO Emergency Response Framework which specifies as an essential requirement the provision of administrative and logistic support to ensure an effective and rapid-response system.”

Among the WHO’s six specific objectives are to preposition outbreak supplies and equipment so they are ready to move when needed. To accomplish this, the plan recommends developing storage hubs and a warehouse and inventory management system, among other things.

![A man receives a certificate of health from the Elwa clinic, an Ebola treatment center in Monrovia, Liberia, in July 2015. [AFP/GETTY IMAGES]](https://adf-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/GettyImages-481472688_edit.jpg)

treatment center in Monrovia, Liberia, in July 2015. [AFP/GETTY IMAGES]

The AU intends to place cars and mobile homes from donors in Douala. When it comes to electronics equipment, such as laptop computers and tablets, rather than buy in bulk and store them for indeterminate periods, officials instead will sign advance agreements with manufacturers in hopes of being able to procure them within 48 to 72 hours, Djoudalbaye said. “So that if there is a need, we can say, ‘Okay, guys, please can you fly 1,000 laptops in this area for us,” he said. “Those are the things that we are trying to put together now … so that we have a preparedness plan ahead, a contingency and preparedness ahead so that tomorrow if there is a crisis … we will be able to overcome the challenges that we have faced with ASEOWA.”

THE AFRICAN CDC

The Ebola outbreak also served to fast-track plans to establish the African Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (African CDC). A coordinating center will be in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and there will be five regional centers: one each in Central Africa, East Africa, North Africa, Southern Africa and West Africa.

The African CDC will help authorities speed up detection, preparation and response to outbreaks. Ebola raged in West Africa for months before authorities recognized it as a global health concern. With the regional centers, resources and detection capacities will be closer when outbreaks occur, regardless of the region.

Each area will designate a host nation for the regional center, which then will be assessed by teams from other global CDCs. Nominations for regional centers were to have been made by December 31, 2015. A governing board composed of two Health Ministry officials from each region and an advisory group of technical partners will oversee operations. The long-term goal is for individual countries to have national centers with similar capacities.

Officials hoped to have the coordinating center open in the first quarter of 2016. Regional centers were expected to open later.

AFRICAN VOLUNTEER HEALTH CORPS

The African CDC provides a permanent, regionalized structure for responding to disease outbreaks across the continent. But the AU also is working on another layer of capacity that will improve the ability to respond rapidly during health emergencies. The AU’s Assembly of Heads of State and Government in June 2015 asked the AU Commission to work with development partners and member states to establish an African Volunteer Health Corps (AVoHC).

“The idea is to have a kind of standby workforce to be mobilized at any time,” Djoudalbaye said. “We are going to establish a roster, and the people who will be on the roster, we will call them for training maybe once or twice in a year. But the mission of the African Health Corps will be to address the priority public health concerns in Africa through prevention, through detection and through response.”

All of these developments, either inspired or fast-tracked by the West Africa Ebola outbreak, will serve to put the right people and the right resources closer to every part of the continent, ready to respond whenever a health problem emerges.

“Our motto is now, ‘Earlier, faster, smoother and smarter,’ ” Djoudalbaye said. “We need earlier detection, faster response, smoother coordination and smarter response. So this is something that we are going to work on.”

East Africa Launches Program to Prevent, Control Pandemics

VOICE OF AMERICA

[REUTERS]

In January 2016 at a hotel in Nairobi, Kenya, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) launched the East African component of FAO’s Emerging Pandemic Threats (EPT-2) program. It is designed to help detect, prevent and control new “zoonotic” diseases — those that can be passed between animals and humans.

Subhash Morzaria, global coordinator of the EPT-2 program, said these diseases can be transmitted through the air or by touching infected fluids or materials. “Whatever the mode of transmission … if these infectious diseases persist in our animal populations, then we have a constant risk of this disease potentially becoming pandemic and causing huge, huge outbreaks and morbidity and mortality in humans, and in animals as well,” he said.

Other zoonotic diseases are HIV/AIDS, influenza — including those commonly known as avian flu and swine flu — and SARS, MERS-CoV, Marburg and Nipah. An estimated six of every 10 infectious diseases in humans are spread from animals, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The United Nations predicts the world population will grow to 9.7 billion from the current 7.3 billion in 2050. This rapid increase means the demand for food also will rise.

“Now these production systems will change very rapidly to meet this demand, and it’s possible that some very risky practices in the production of livestock might occur, and these risky practices might create an environment for evolution of new pathogens and spread,” Morzaria said.

Kenya’s director of veterinary services, Dr. Kisa Juma Ngeiywa, said new pathogens can spread further than ever in today’s mobile society.

“Let me use the H7N9 influenza, which was in China,” Ngeiywa said of the strain of avian influenza. “Now, if you look at the airplanes — Kenya Airways, Ethiopian Airlines, and others — they are going to China and they are coming to Kenya, every day. So, because of that there is a big vulnerability, unless we put measures [in place] to be able to see and stop it from spreading.”

Morzaria said everyone has a stake in the process.

“Everybody is at threat,” he said. “The virus doesn’t distinguish between a poor and a rich person. It goes and infects, and it kills that person if it’s highly infectious and pathogenic. So I think this is a global concern.”

In October 2015, USAID announced $87 million in new funding for the program. The money will be used to help governments and veterinary services better understand livestock systems and help conduct surveillance, as well as identify current and potential pathogens.