REUTERS

Beneath the scorching sun that beats down on Senegal’s savanna, the verdant gardens of Ndem village are a sanctuary.

Within a hibiscus fence, rows of vegetables grow under fruit trees. Men with dreadlocked hair and women in colorful robes dye fabrics and stitch handbags destined for luxury boutiques and furniture companies.

They are members of Baye Fall, a branch of Senegal’s Muslim Mouride brotherhood, who believe that labor is a form of prayer. In Ndem, they have created an oasis in a region long plagued by drought.

“We are pushed towards the love of sharing, of work, reflecting on the improvement of living conditions in our environment in harmony with nature,” said 29-year-old Fallou Mbow, whose great-great-grandfather founded the village.

Mbow’s parents and others founded the nongovernmental organization Ndem Villagers in 1984 to manage a range of development projects. Since then, the group has grown to about 4,600 members who have renewed the landscape with the help of irrigation systems and solar power.

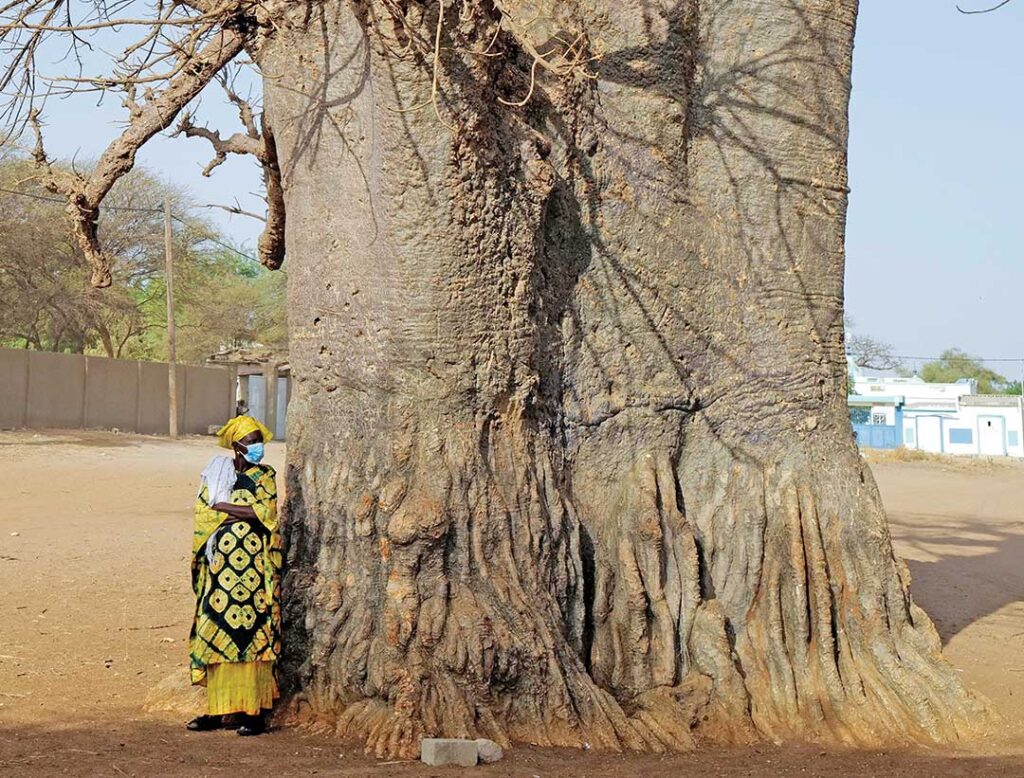

“It’s only in Ndem that there are these kind of work opportunities,” said Mame Diarra Wade, one of 120 women who process baobab fruit into a consumable powder. “We are happy to see those from the surrounding villages come to work with us.”

At the request of Mouride leaders, the Mbow family moved in 2015 to another village, nearby Mbacke Kadjior, to replicate their success. That village now boasts busy craft workshops and sprawling gardens too.

“One of the main objectives is to really slow down the rural exodus,” said Maam Samba Mbow, Fallou Mbow’s younger brother, “to create a dynamic local economy that is good for villagers, so they can have a happy life with interesting activities instead of leaving to find work in the big city.”