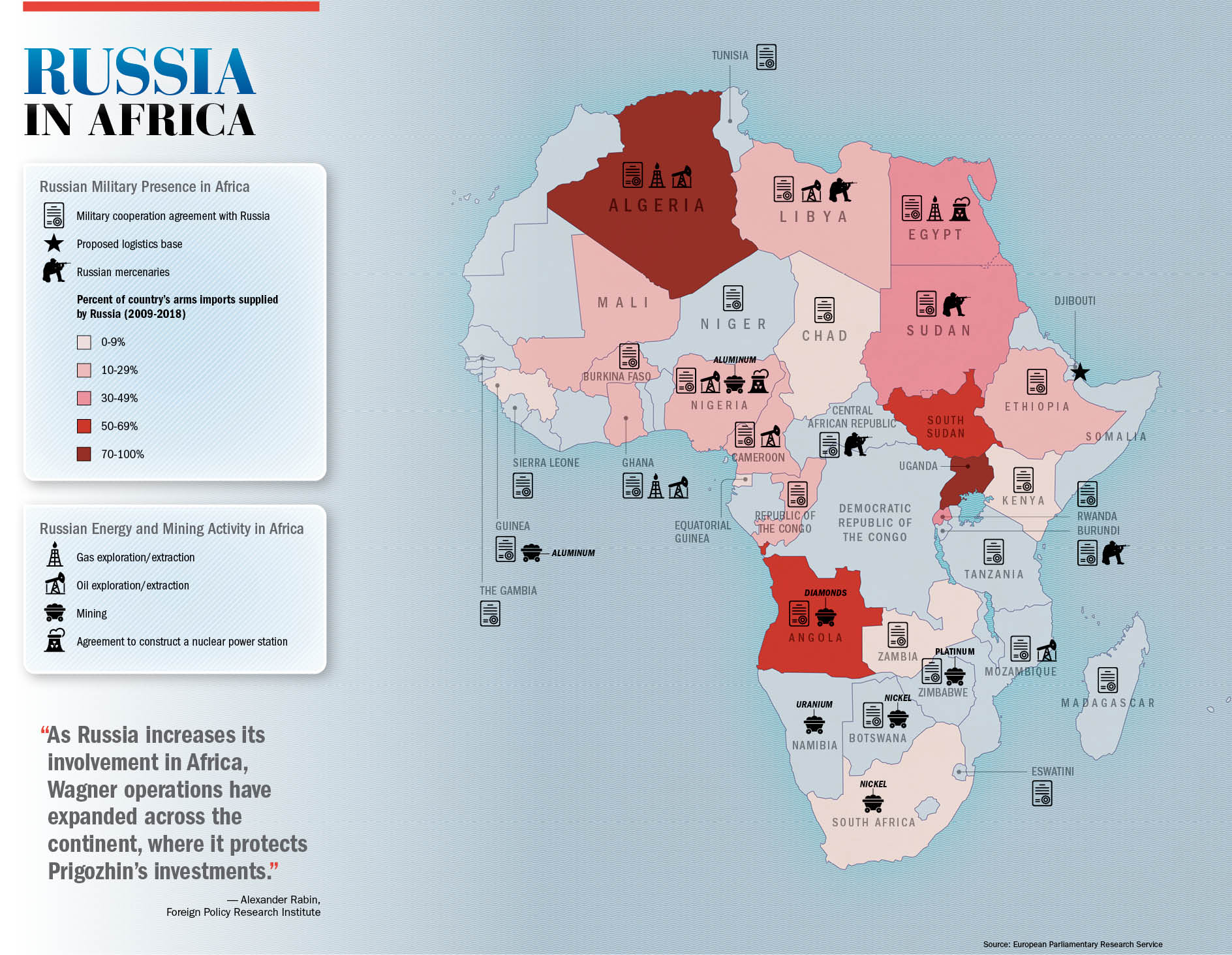

In Russia’s frenzied attempt to flex its muscles, get access to natural resources and increase its geopolitical relevance, it relies heavily on private military companies (PMCs). This strategy produces a small foreign footprint and offers the Kremlin plausible deniability while enriching a small circle of people.

President Vladimir Putin’s Russia favors the use of PMCs such as the Wagner Group when forging training and security deals with African nations while positioning itself to access mines and other rich resource repositories.

“They act as force multipliers, arms merchants, trainers of local military and security personnel, and political consultants,” according to the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace article, “Implausible Deniability: Russia’s Private Military Companies,” by senior fellow Paul Stronski. “Nominally private actors, they extend the Kremlin’s geopolitical reach and advance its interests. Versatile, cheap, and deniable, they are the perfect instrument for a declining superpower eager to assert itself without taking too many risks.”

The Wagner Group, the most prominent of Russia’s PMCs, emerged from conflict in the Ukraine in 2014, starting with about 250 men and growing to 10 times as many, according to September 2020 paper by researcher Sergey Sukhankin. They were sent to Syria, where they supported President Bashir al-Assad’s forces and have since made their way into Africa.

“Aside from in Ukraine, Syria and Libya, the Wagner Group has appeared in countries of Sub-Saharan Africa as a ‘shadow facet’ of the military-technical cooperation between Russia and local states,” Sukhankin wrote in “Russian Private Military Contractors in Sub-Saharan Africa: Strengths, Limitations and Implications” for the Institut français des relations internationales.

Despite denials and obfuscation from official Russian government sources, observers generally agree that the Wagner Group is a proxy arm of the government with connections to the national security apparatus, Putin’s rich cronies and the president himself. However, successfully documenting these connections can be challenging.

Even so, Wagner forces have been known to operate in a number of African nations, including the Central African Republic (CAR), Libya, Madagascar, Mozambique and Sudan. Their presence often coincides with the business interests of one of Putin’s closest allies, the oligarch Yevgeny Prigozhin.

PUTIN’S CHEF

Despite his close association with Putin, Prigozhin did not start the Wagner Group. That credit falls to Dmitry Utkin, a veteran of the Chechen wars and a former member of the Russian intelligence service known as the GRU.

Utkin worked for the Moran Security Group in Syria, quitting in 2014 to found Wagner, so named for his former call sign, “Vagner.” It was a nod to the German composer Richard Wagner, whose works Hitler appropriated for the Third Reich.

Although not a company founder, Prigozhin’s influence is said to be key in how the group’s forces are employed. Prigozhin’s personal history is an extraordinary one: A Soviet court convicted him of robbery and other offenses, and he served nine years in prison. Once released, he hawked hot dogs from a kiosk and eventually opened a restaurant on a docked boat. After serving a meal to Putin there, Prigozhin found favor with the Russian leader and soon was catering Kremlin affairs, becoming known as “Putin’s chef.”

As Russia transitioned out of its Soviet past and into newfound capitalist ventures in the 1990s, Prigozhin opened St. Petersburg’s first grocery store chain, and soon luxury restaurants, according to a report from Turkish news service TRT World.

Prigozhin eventually was drawn into Putin’s inner circle, where he found lucrative high-dollar military and school catering contracts. Soon, he had turned his business toward construction and a range of other interests. Often his interests and those of the Kremlin found common ground in places as far-ranging as Syria, Libya and in Sub-Saharan Africa.

“Simply put, the company’s presence in geopolitical hotspots illuminates coordination between Prigozhin’s commercial ambitions and the Kremlin’s pursuit of its national interests,” Aruuke Uran Kyzy of TRT World Research Centre wrote.

EXTENDING PUTIN’S REACH

What could a small, private security company possibly do to advance Russian geopolitical aims in Africa and elsewhere?

Perhaps the most valuable asset the Wagner Group offers Putin is plausible deniability. Russia’s Constitution reserves all defense and security functions for the government, so establishing PMCs is illegal. However, loopholes allow registering companies abroad and state-run enterprises to have private security forces. In Wagner’s case, there’s no evidence that it is registered anywhere.

Putin’s deployment of Wagner outside Russia gives him and his government influence in other nations without the publicity and liability that comes with national military interventions.

For example: If Wagner is deployed in a conflict in an African country and suffers embarrassing losses, as happened while fighting Islamist militants in northern Mozambique, the Russian government does not have to endure the public fallout associated with losing national military troops during an ill-fated adventure on foreign soil.

Russian personnel arrived in Mozambique as the two countries forged agreements that will give Russian businesses access to liquefied natural gas, which is plentiful in the nation’s north.

Russian personnel arrived in Mozambique as the two countries forged agreements that will give Russian businesses access to liquefied natural gas, which is plentiful in the nation’s north.

Also plentiful in the north are violent insurgent attacks by a relatively new terrorist group, Ansar al-Sunna, which has aligned itself with the Islamic State. Well-equipped Wagner forces brought in to help an overmatched military soon took significant and embarrassing losses due to their ignorance of the local terrain and their inability to effectively communicate with government forces. They soon departed.

Although the Mozambique engagement went poorly, Wagner personnel tend to be battle-hardened fighters as opposed to retirees or veterans. This provides a ready-made fighting force that allows the Russian government to pursue its foreign policy aims without leaving fingerprints.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Wagner’s presence often ends up aligning with Prigozhin’s business interests. His Evro Polis energy company entered into a contract with Syria’s state-owned General Petroleum Corp. The Associated Press reported in December 2017 that the contract guaranteed Evro Polis 25% of proceeds from oil and gas production at fields its contractors take and protect from the Islamic State.

“Similarly, as Russia increases its involvement in Africa, Wagner operations have expanded across the continent, where it protects Prigozhin’s investments,” wrote Alexander Rabin for the Foreign Policy Research Institute in 2019.

In 2017 and 2018, Prigozhin’s personal plane was found to have headed to African countries numerous times. Trips included Angola, the CAR, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Libya, Madagascar, Mozambique, Sudan and Zimbabwe, according to Sergey Sukhankin’s January 2020 Jamestown Foundation report, “The ‘Hybrid’ Role of Russian Mercenaries, PMCs and Irregulars in Moscow’s Scramble for Africa.”

The report notes that all of these countries hold three things in common:

Each is known for social and political instability.

All are “handsomely endowed with strategically important natural resources.”

Each used to be part of the influence spheres of colonial powers such as Belgium, France and Portugal — nations that Russia no longer considers capable of fending off its involvement in the countries.

Corruption and insider deals soon follow lines similar to those in Syria, according to Sukhankin: Moscow secretly strikes a bilateral deal with the nation’s leaders and offers military and security support in exchange for natural resource concessions.

“Under this scheme, a portion of the profits allegedly go to the Russian state budget (via the companies/corporations involved), while the rest is distributed among private individuals who, in fact, may be closely associated with the government,” Sukhankin wrote.

After rumors in late 2017 that Russian mercenaries had been sent to the CAR and Sudan, two companies connected to Prigozhin — Lobaye Invest and M-Invest — won licenses to extract gold, diamonds, uranium and more, Sukhankin wrote. Reports also indicate that Wagner personnel provide a security detail for CAR President Faustin-Archange Touadéra and guard gold mines.

In 2018, three Russian journalists were murdered while investigating the entry of Wagner Group forces into the CAR from neighboring Sudan, where Wagner had been training local security forces. By 2019, talk had turned to the potential for a Russian base in the CAR.

On the surface, the CAR would seem to be an unlikely target for Russian presence and influence. However, the nation’s longstanding instability — and its rich deposits of diamonds, gold, uranium and oil — make it a desirable center of influence for Russia. Putin deftly exploited the situation there by employing a Cold War Soviet-era model that relies on “military-technical cooperation,” according to an analysis by the Jamestown Foundation. The CAR and Russia signed an agreement in August 2018, and Russia since has expanded its footprint in the country using two methods.

First, a military training/consulting agreement began in March 2018 with the arrival of advisors consisting of five military personnel and 170 “civilian instructors,” according to the foundation. Despite statements to the contrary, these instructors are in fact Wagner forces.

Second, Russia has given CAR’s government military and technical equipment that includes weapons, ammunition and military vehicles. Most of this assistance is rendered cheaply, as much of the equipment is dated. Also, Russia’s goals tilt more toward economic benefits than ideology, according to Jamestown.

Despite this alleged assistance, there is evidence that Russia may be using Wagner to play both sides in the CAR.

For example, Geopolitical Monitor noted in August 2020 that more than 80% of the country remained under rebel control. “Wagner, along with providing military training, allegedly collaborates with these rebels to exploit the local population,” Daniel Sixto wrote. “Wagner forces reportedly coordinated with rebel forces to allow a Russian mining company to access diamond mines in insurgent territory, undermining their wider objective in the region.”

In Libya, Russia has used Wagner to intervene in the conflict on the side of Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar against the United Nations-recognized Government of National Accord, which preceded the interim government under Abdul Hamid Dbeibah, known as the Government of National Unity. Libya also is rich in oil deposits, and its Mediterranean coast makes it a highly strategic potential sphere of influence.

U.S. Africa Command has accused Wagner forces of planting mines and other explosive devices in Libya, sometimes hiding them in toys, according to Business Insider.

Wagner and Prigozhin also extend influence into the online realm. Reports indicate that Wagner has been behind online influence campaigns in Libya that target citizens and bolster Haftar and Saif al-Islam Gadhafi, the late dictator’s son. Similarly, the group is known to have tried to influence the 2018 elections in Madagascar.

Wagner isn’t just an advantage for Putin, Prigozhin or the Russian government. Those working abroad for Wagner also benefit, most notably financially. According to TRT World, Wagner troops can earn 1 million rubles over three months — the equivalent of up to $16,000. That can be up to 10 times what they would make as a Russian soldier. Wagner commanders can earn up to three times more. If killed in action, the fighter’s surviving family can get about $56,000.

“Wagner is deployed by Russia as an extension of its foreign and military ambitions, and authoritarian regimes just so happen to be the clients,” Ahmed Hassan, CEO of intelligence consultancy Grey Dynamics, told Business Insider. “Of course, those type of regimes often try to solve civil unrest by force, and Wagner is such a tool.”