Long-serving dictators have many tricks to help them hold onto power. One is a process known as “coup-proofing,” or building armed forces that will not rebel.

Political scientist Philip Roessler said leaders attempt to coup-proof a regime in three ways:

Purge the military ranks of any members who might oppose the leader.

Give preferential financial and political treatment to top military commanders.

Employ a tactic known as “ethnic stacking.”

In ethnic stacking, the leader of a country fills his top military ranks with officers of his own ethnicity.

Ethnic stacking can help a leader stay in power, but it almost inevitably leads to corruption and poor governance. It also leaves a leader vulnerable. As political scientist Nandita Balakrishnan wrote in The Washington Post, “Military leaders are still the only ones strong enough to oust them — even if coups are harder to mount and more dangerous should they occur, because failed coup plotters and their families often face execution.”

It’s a lesson as old as history: When you’re in power and surround yourself with your kinsmen to the exclusion of others, your country will suffer for it.

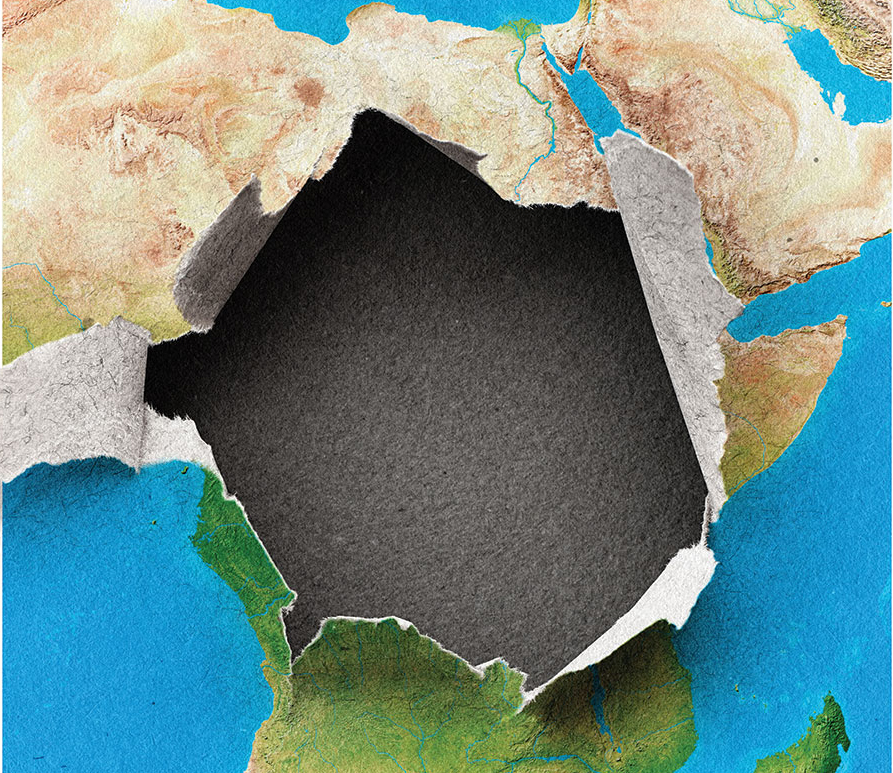

Africa has been through a lot of coups. Since decolonization began in the 1950s, there have been more than 220 coup attempts on the continent, with nearly half of them successful, overthrowing civilian governments, undermining democracy and the rule of law, and leading to years of military dictatorships.

Since 2010, there have been 34 coup attempts on the continent. Six were successful. In the rest of the world during that time, there only were seven coup attempts.

American political scientist Jonathan Powell says the number of coups is not surprising, given the instability African countries experienced in the years after independence.

“African countries have had the conditions common for coups, like poverty and poor economic performance,” he told the BBC. “When a country has one coup, that’s often a harbinger of more coups.”

ELITE UNITS

Typically, a new leader will announce a plan for inclusion, promising that all ethnic groups, religions and tribes will be included in his or her administration. But if the previous leader’s inner circle was ethnically based, this new inclusion process will not go over well, forcing the new leader to stick with people already in power, or risk a coup. In many cases, chiefs of state will use their ethnicity as a criterion for membership in elite or privileged units, such as top military leadership posts.

Scholars have recently devoted considerable attention to ethnic stacking, linking it to authoritarian repression, coups and political violence.

A case of successful ethnic stacking took place in the Democratic Republic of the Congo when it was still named Zaire. After taking office in 1965, President Mobutu Sese Seko stacked his officer corps with Ngbandi men from his native Equateur region. Dr. Emizet Kisangani, a professor of political science, said that by the time Mobutu’s rule ended 30 years later, Mobutu’s Equateur kinsmen made up almost 80% of his officer corps.

Mobutu’s stacking enabled him to stay in power for three decades, but his presidency can hardly be called successful. With the support of his stacked army, Mobutu amassed vast wealth, mostly through corruption and economic exploitation. His administration was marked by uncontrolled inflation and economic disaster.

Dr. Kristen Harkness, a senior lecturer at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, has studied ethnic stacking extensively. Her 2018 book, When Soldiers Rebel, analyzes ethnic recruitment practices in African armies and how those practices have destabilized regimes.

“Since decolonization, worried by the possibilities of coup attempts and ethnic insurgencies, many leaders have continued to rely on the recruitment and promotion of co-ethnics to control the military and ensure its loyalty,” Harkness wrote in a 2019 study. “Such practices range from ethnically manipulating the highest ranks of the command hierarchy, to creating elite co-ethnic paramilitary units, to conditioning all service on shared ethnicity.” She added that, “Such dependence on ethnicity as a shortcut for loyalty likely has profound consequences for a range of important outcomes, from combat effectiveness to coup propensity to democratization.”

The downsides of such policies are numerous. The process of building ethnic armies, Harkness said, “likely inspires resistance from out-group officers, thereby destabilizing governments, at least in the short term.” Other researchers have noted that excluding ethnic groups from important state institutions can inspire insurgency and even terrorism.

Harkness’ research showed that when elections bring to power a new leader who is ethnically different from the existing ethnically constructed army, the risk of a military coup rises from under 20% to almost 90%.

NOT NEW TO AFRICA

Ethnic stacking existed long before African independence. An extreme example was in apartheid South Africa, where blacks were barred from serving in the military. Armed forces in other countries in pre-independent Africa often were stacked by their colonial leaders with members of a particular tribe, perceived to be better soldiers than were other tribes.

Today, the South African National Defence Force has racial quotas to make sure that white, black, mixed-race and Indian South Africans are proportionately represented.

Harkness notes that some African nations have continued to use ethnic stacking while still reaching out to other ethnic groups.

“Only the very top of the command hierarchy is controlled via ethnic loyalty, with often great care taken to cultivate inclusiveness at lower ranks,” she wrote.

Since Kenya’s independence in 1964, its leaders historically have stacked their Armed Forces’ leadership ranks with members of their own ethnic group. The country’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta, inherited an army overwhelmingly staffed with Kamba officers. He acted quickly to change the ethnic balance in the Armed Forces in favor of his own ethnic group, the Kikuyu. He was only partially successful; the Kikuyu made up only 21% of the country’s population at that time. Daniel Moi, Kenyatta’s successor, replaced Kikuyu leaders with members of his own Kalenjin ethnic group. After an unsuccessful coup attempt, Moi removed most of the few remaining Kikuyu from positions of authority.

Today, globalsecurity.org reports, the Kenyan Armed Forces observe ethnic quotas within their ranks and maintain a diversity of Soldiers at

all ranks.

Ethnic stacking can be a complex subject, because Africa’s ethnic identities are not always clear. In many parts of Africa, ethnic identity can be identified by region, mixed ethnic groups and clans. There are subgroups within ethnic groups that are associated with regions.

“Region has shaped ethnic stacking in many Sahelian states, where important north-south divides overlap ethnic, religious, linguistic and racial cleavages,” Harkness wrote.

Harkness and other scholars have concluded that ethnic stacking works, but only if the goal is to remain in power. If the goal is a true democracy and a true equal-opportunity armed forces, ethnic stacking must be eliminated. In their 2007 study, Staffan Lindberg and John Clark concluded that true democratic regimes have a “significantly different track record” of being subjected either to successful or failed military interventions. Their research indicates that democratic regimes are 7.5 times less likely to be subjected to attempted military interventions than are electoral authoritarian regimes and almost 18 times less likely to be victims of actual regime breakdown.

“Legitimacy accrued by political liberalization seems to ‘inoculate’ states against military intervention in the political realm,” they wrote.

In a 2009 study on ethnic stacking, researchers Andreas Wimmer, Lars-Erik Cederman and Brian Min drew three conclusions:

Armed rebellions are more likely to challenge states that exclude large portions of the population on the basis of ethnic background.

When a large number of competing elites share power in a segmented state, the risk of violent infighting increases.

Incohesive states with a short history of direct rule are more likely to experience secessionist conflicts.

Harkness said that true democracy comes at a price.

“If democracy is to thrive in multi-ethnic societies, existing ethnic armies must be dismantled and national military institutions diversified,” Harkness wrote. She added that dismantling these institutions is both difficult and dangerous. “Ethnic armies do not stand idly by and allow for their own demise.”