The Security Structure in the Yaoundé Code of Conduct is Taking Shape in the Gulf of Guinea

ADF STAFF

Security professionals in the Gulf of Guinea know that if they want to spot criminals in the open water, the best place to look is along a maritime border.

Historically, this has been the space where pirates, illegal fishermen and traffickers felt safest knowing that, if confronted, they could flee into another country’s waters.

“That is the whole business of the bad guys,” said Senior Capt. Boniface Konan of the Côte d’Ivoire Navy. “Even if you look on [the automatic identification system], you will see these groupings right there on the borderline of each country.”

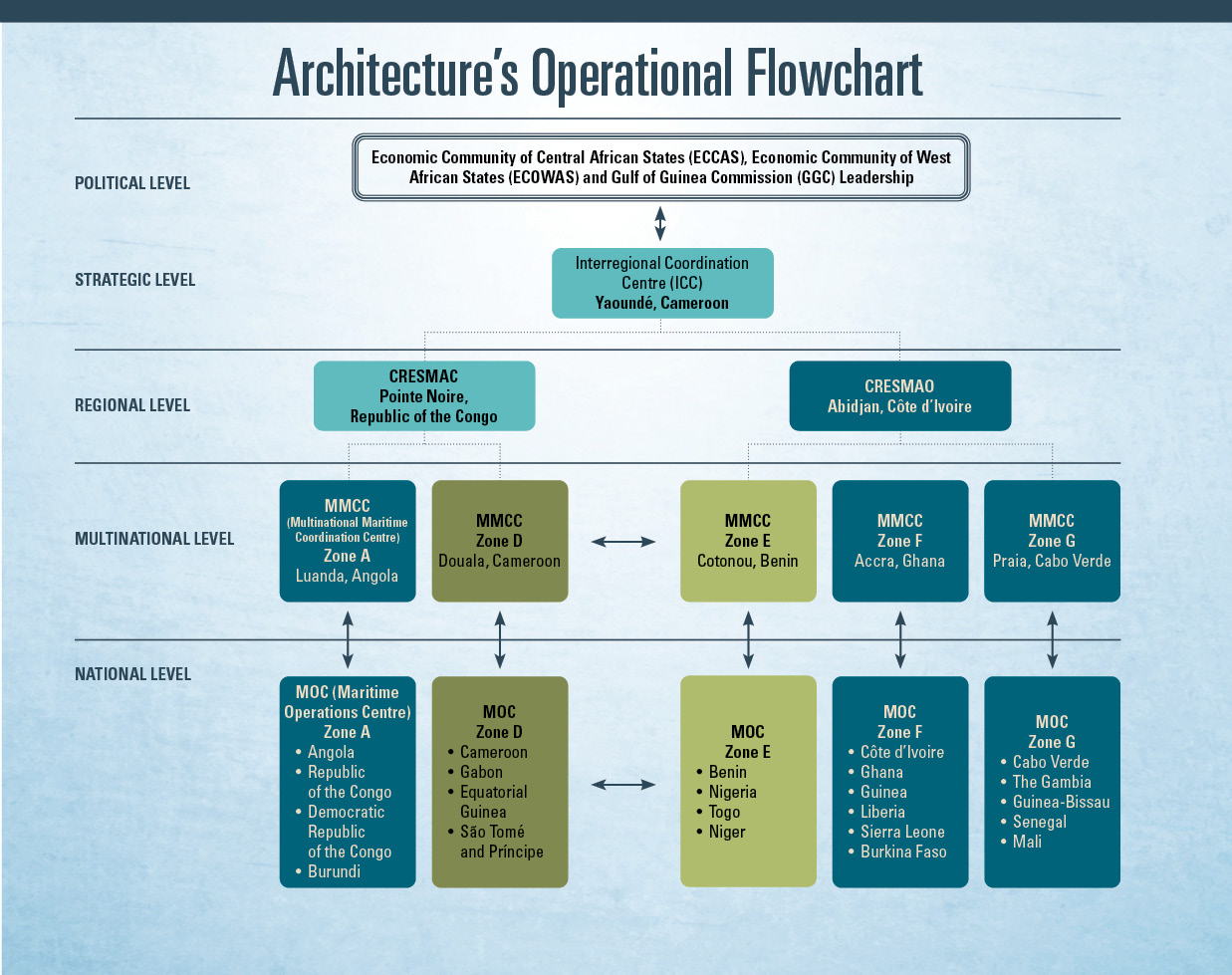

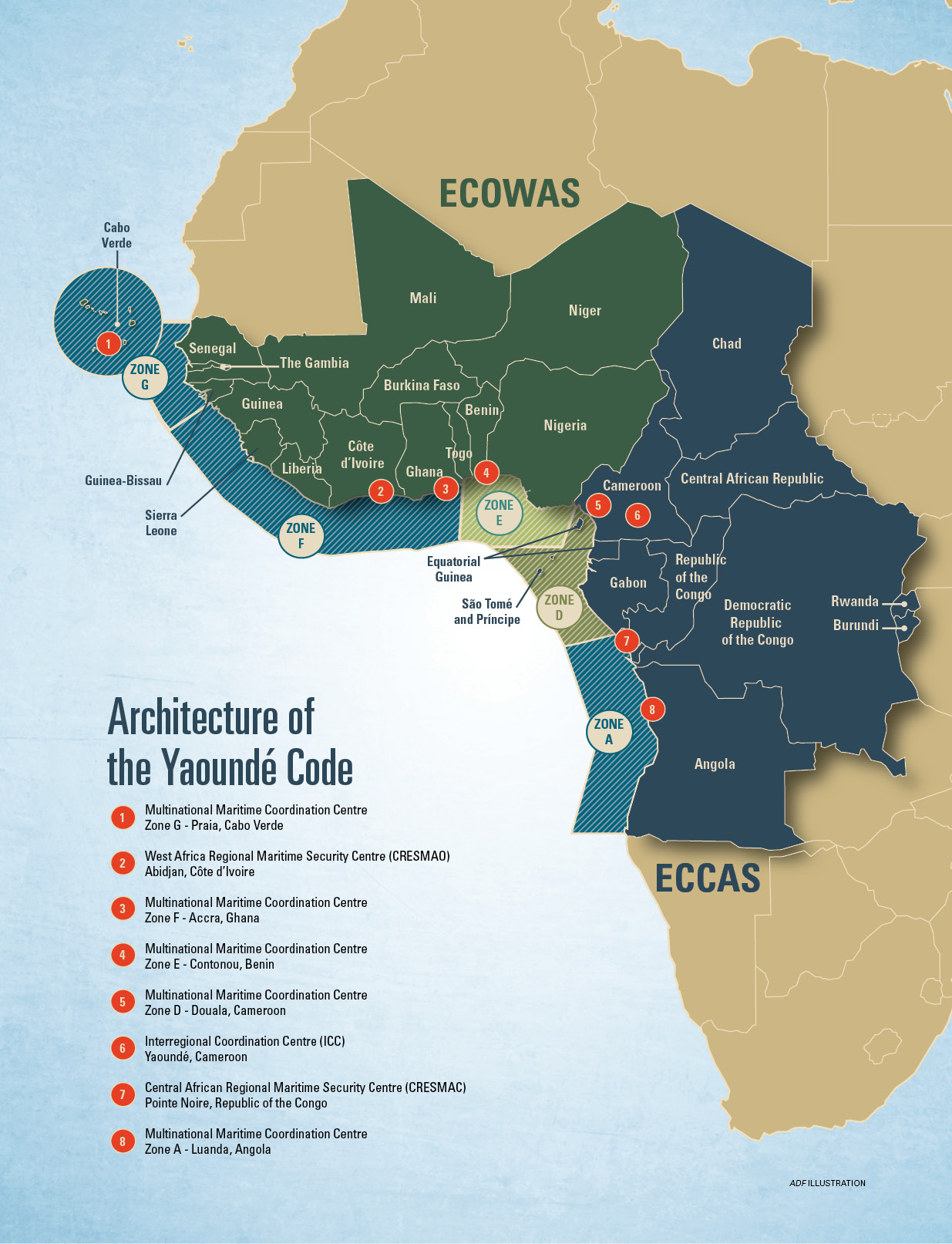

Thanks to a regional maritime security architecture, these safe havens are being shut down. The Yaoundé Code of Conduct was signed in 2013 by 25 countries in West and Central Africa. It provides the structure for joint operations, intelligence sharing and harmonized legal frameworks. The code includes five zones, two regional centers and one Interregional Coordination Centre (ICC) that watch over 6,000 kilometers of coastline and 12 major ports.

Konan, acting director of the Maritime Security Regional Coordination Centre for Western Africa (CRESMAO), headquartered in Abidjan, said no country can handle maritime security alone.

“We are now sharing the load of the job,” he told ADF. “Facing the threats in the Gulf of Guinea, the heads of states understood that not one country can do it by itself. The EEZ (exclusive economic zone) might be 200 nautical miles out to sea, but you still have very tiny coastline. So you cannot do an operation just by staying within your own coastline.”

Konan said this cooperation was on display in December 2018 when the Ghana Navy spotted suspicious vessels it believed were bunkering oil in its waters near the border with Côte d’Ivoire. Ghana posted the information to the zonal center, Multinational Maritime Coordination Centre Zone F in Accra, which relayed the information to CRESMAO in Abidjan. CRESMAO alerted the Côte d’Ivoire Navy, which intercepted the vessels.

“You had Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire working the case together, and it went all the way to a debriefing in Abidjan at the CRESMAO center,” Konan said. “The ships were detained and then processed through each of the countries’ own legal system.”

YAMSS Takes Shape

The idea behind the Yaoundé Architecture for Maritime Safety and Security (YAMSS) is simple. Share information, coordinate action, strengthen laws and close down areas of vulnerability.

Konan said years ago the region’s navies were afflicted by the metaphorical disease of “sea blindness.” They didn’t know what their neighbors’ navies were doing, and they didn’t know what threats lurked beyond their borders.

In the YAMSS system, information is designed to cascade up from national navies, fisheries and ports. Information also is meant to cascade all the way down from the ICC and regional level to the ships on the water.

YAMSS “is not merely a nice idea on paper; it is increasingly producing real results on the water,” wrote Dr. Ian Ralby, Dr. David Soud and Rohini Ralby in a paper for the Center for International Maritime Security. “Furthermore, the community of maritime professionals involved in implementing this architectural design are increasingly connected with each other and working collectively to make maritime safety and security a reality in the Gulf of Guinea.”

Improvement is urgent. In 2018, there were 72 attacks on vessels in the waters between Côte d’Ivoire and Cameroon. That is more than double the total in 2014, when 28 vessels were attacked. Through the first six months of 2019, 30 attacks were recorded, making the region the world’s worst piracy hot spot, the International Maritime Bureau (IMB) reported.

Improvement is urgent. In 2018, there were 72 attacks on vessels in the waters between Côte d’Ivoire and Cameroon. That is more than double the total in 2014, when 28 vessels were attacked. Through the first six months of 2019, 30 attacks were recorded, making the region the world’s worst piracy hot spot, the International Maritime Bureau (IMB) reported.

The IMB said that 130 of the 141 hostages taken globally in 2018 were captured in the Gulf of Guinea.

Cameroonian Navy Capt. Emmanuel Isaac Bell Bell of the ICC based in Yaoundé said the attacks are real, but so is the progress. In May 2019, for instance, the Togo Navy rescued seafarers and arrested eight pirates after an attack near Lomé. That same month, authorities foiled a similar attack in Equatorial Guinean waters and arrested 10 pirates.

“I think day to day we speak a lot about the incidents that happen,” Bell told ADF. “We don’t talk enough about the incidents that were avoided, thanks to the measures that the states have taken individually and collectively.”

In its role at the strategic level, the ICC is driven by four main pillars:

- Promote the Exchange of Information: Maritime operations centers on a national, zonal and regional level must know what one another are doing. Bell said the ICC communicates with stakeholders via email, phone and online chat and compiles a weekly report.

- Harmonize Legislation: Many countries have outdated and inadequate maritime laws. For example, a number of West African countries do not have statutes in place to prosecute pirates. Some only allow prosecution of their own nationals. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime is working with nations to modernize their laws.

- Conduct Regional Training and Exercises: There are now a number of annual exercises around the region that promote cooperation and information sharing. The U.S. sponsors the annual Obangame Express exercise, and France hosts the Navy’s Exercise for Maritime Operations. The ICC also is partnering with universities to offer educational opportunities to maritime security professionals.

- Promote Joint Law Enforcement Operations: In order for the navies of multiple nations to collaborate, there must be memoranda of understanding outlining what is and is not permitted. It is also helpful to have harmonized standard operating procedures so all navies, police, coast guards and other security forces follow the same rules to arrest, detain and prosecute criminals caught at sea.

The Way Forward

Leaders of the YAMSS say the system is functioning but still is a work in progress. The two regional centers are operating but are still awaiting international staff from some member countries. CRESMAO has not moved into its permanent headquarters.

In the coming years, a number of issues will need to be sorted out to improve performance. One of them is delineating maritime borders. Several Gulf of Guinea countries have disputed or unmarked maritime borders. Another issue involves interagency cooperation. For the system to be effective, YAMSS must develop memoranda of understanding from national agencies including fisheries and transportation departments in individual countries.

Finally, there needs to be agreement on the command and control structure when a vessel passes from one nation’s waters to the next and from one zone to the next. Issues include standard operating procedures of when to stop, board and search a vessel, and who has the right to do so.

Konan stressed that these issues are being worked out, but the navies of the region are not going to wait for perfection. They’re already collaborating.

“The navies and the actors at sea are not waiting for CRESMAO to be fully staffed. The culture of working together, since the Yaoundé Code of Conduct, it’s already functioning,” he said.

Another step urged by Ralby and his co-authors is the acquisition of affordable maritime domain awareness (MDA) and surveillance technology at the regional and ICC level. Although the ICC and regional centers have MDA capabilities, Ralby said additional tools to track illegal fishing, transshipment of cargo and bunkering can pay for themselves.

“If law enforcement agencies can show that their efficiency is such that they have successful interdictions nearly every time they deploy assets, that success can become contagious,” Ralby and co-authors wrote. “It can help energize the maritime agencies, deter criminal actors, and at the same time build the political will to ensure the longer-term safety and security of the maritime domain.”

The end goal will be to integrate YAMSS into a continentwide system as envisioned by the African Union. This 2050 Africa Integrated Maritime Strategy would have regional coordination centers encircling the continent and, eventually, a combined exclusive maritime zone that erases barriers and promotes trade.

When this happens, Konan said, there will be no border that inhibits security operations. Cooperation will be the norm rather than the exception.

“We know that we must not kill the borders. They are economic borders, and we should keep them as economic borders,” Konan said. “But in terms of security, we are going to break all of these borders.”