Many countries suffer from an affliction colloquially known as “sea blindness.” The phrase describes a general lack of concern about maritime security, but also the inability to monitor what is happening on the water.

Just how much activity is going on in these blind spots? In a report published in the journal Nature, researchers found that about 76% of industrial fishing vessels were “dark” at some point, meaning they were not broadcasting their location or were not tracked by public monitoring systems. The same report found that nearly 30% of energy and transportation vessel movement was not tracked.

The implications are enormous because analysts believe vessels involved in illicit acts such as trafficking, piracy and terrorism are similarly going undetected.

“The maritime environment continues to serve as a silent stage for high-stake activities,” Kenyan data science researcher Wekesa Lucas wrote. “The threats found offshore — whether illegal fishing, smuggling or foreign surveillance — are quieter, faster and less visible than those on land but no less consequential.”

Ninety percent of African trade moves through maritime routes, but leaders say security concerns continue to focus overwhelmingly on land. In an editorial published in The East African, Abdisaid Ali, chairperson of the Lomé Peace and Security Forum, urged nations to change this approach by investing time and resources in maritime security. Ali wrote that the question is no longer “do the seas matter?” The question is “do we control some of the most strategic corridors” in the world?

“Africa must invest urgently in coastal surveillance, maritime intelligence fusion centres and naval command capacity,” Ali wrote. “Maritime security is not simply about defending waters. It is about controlling the flow of goods, data, energy, and influence. In this domain, control is strategy.”

The ability to control security at sea starts with maritime domain awareness (MDA). A recent explosion of technology and the creation of frameworks to share data across borders have made MDA something all countries can afford and achieve.

Improved Monitoring

One of the most important tools for tracking vessels is free and open for all to use. Ships above a certain tonnage are required to operate an automatic identification system (AIS) that broadcasts their location several times per minute. Data from these transponders can be accessed through online tools to chart a ship’s movement. Commercial fishing vessels are similarly required to install vessel monitoring systems (VMS), which transmit a ship’s position to a satellite, which then relays it to an onshore monitoring station.

However, these data sources are not foolproof. It is common for vessels to disable these systems so authorities and foes cannot detect them. A 2022 report in the journal Science found that 6% of all global fishing, accounting for millions of hours each year, occurs when vessels are “dark,” or have disabled their monitoring systems. Researchers found correlations between ships going dark and crimes such as transshipment of fish between boats, fishing without a permit or fishing with illegal gear. Some vessels operating illegally might even send out false or spoofed positions to confuse the system.

“Just as thieves can turn off phone location tracking, ships can disable their AIS transponders, effectively hiding their activities from oversight,” Heather Welch, a researcher at the University of California, Santa Cruz, wrote for The Conversation.

To fill those information gaps, countries are turning to radar and satellites. New innovations include synthetic aperture radar (SAR), a satellite-based system that sends radar pulses to Earth, collects their echoes and then processes that data to form an image.

Another cutting-edge tool is the visible infrared imaging radiometer suite (VIIRS), a satellite-based sensor that detects light emitted by vessels to track their movements.

Data from SAR and VIIRS is publicly available, and authorities can use it to track vessels that are otherwise hidden. The more data that is collected, the better authorities can monitor trends and identify hot spots of potential crime.

“This fusion of sources could enable navies and relevant law enforcement to build a more comprehensive and dynamic picture of maritime activities,” Ifesinachi Okafor-Yarwood of the University of St. Andrews School of Geography & Sustainable Development told ADF. “Radar provides near-shore, real-time detection, while satellites offer wide-area coverage and can identify vessels that are not broadcasting AIS.”

One system being used to synthesize this information is SeaVision, an online MDA tool that incorporates AIS, VMS, SAR, VIIRS, coastal radar and other data. The United States created the system in 2012, and it now is used, free of charge, in more than 100 countries. With little cost and few tools required beyond an internet connection, SeaVision lets users access an immense amount of real-time MDA data.

“A multi-faceted technological revolution is bringing MDA within reach of even the smallest of countries, potentially giving them the tools to understand and govern their own maritime domains at an achievable price,” wrote David Brewster, a senior research fellow at the National Security College at the Australian National University, in an article for the website The Strategist.

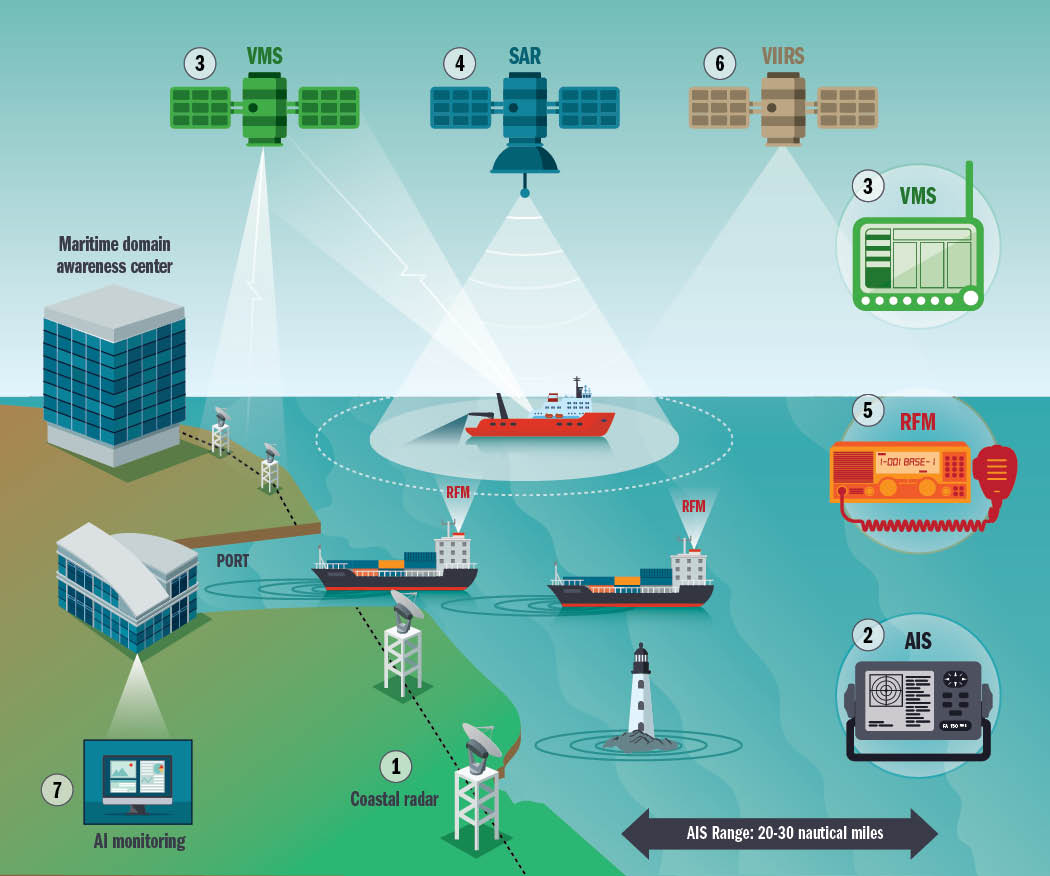

Data Sources for Maritime Domain Awareness

Security officials have access to a variety of data sources to build a picture of the maritime domain. These sources can complement one another, allowing authorities to maintain a watchful eye and collect information even in bad weather or when vessels attempt to remain unseen.

- Coastal radar: These land-based systems emit microwave pulses and analyze the reflected signals to offer a picture of what is on the ocean.

- Automatic identification system (AIS): This shipboard broadcast system must be installed and active on most large ships. It acts like a transponder operating in the VHF maritime band and notifying other ships of its position.

- Vessel monitoring system (VMS): A satellite-based surveillance system primarily used to track fishing vessels.

- Synthetic aperture radar (SAR): It uses radar waves to create high-resolution images of Earth’s surface. Unlike optical sensors, SAR can penetrate clouds and is effective in the dark.

- Radio frequency monitoring (RFM): It detects and analyzes radio signals emitted by ships, including those used for communication and navigation, to determine their location and movements.

- Visible infrared imaging radiometer suite (VIIRS): A satellite-based sensor observes Earth’s surface, atmosphere and oceans in visible and infrared light. It is highly sensitive and can detect faint light sources, including those emitted by ships at night.

- AI monitoring: Computer systems use algorithms to overlay data from multiple sources and look for suspicious or anomalous activity that can be investigated further. This helps security forces focus their efforts.

New Technology Offers Solutions

The extensive amount of data captured by MDA tools can become overwhelming. In response, security professionals are using artificial intelligence (AI) to locate the proverbial needle in the haystack of data and prioritize a response. AI systems can enhance MDA by analyzing patterns to identify suspicious vessel behavior that might be associated with a crime. It also can identify data gaps that need to be filled and help overlay information from multiple sources.

“AI can revolutionize the concept of maritime domain awareness since it can analyze big datasets to identify patterns related to illegal activities,” said Osei Bonsu Dickson, a senior fellow at the Gulf of Guinea Maritime Institute. “Machine-learning algorithms could, for instance, predict routes taken by smugglers or monitor fishing activities to detect violations of maritime laws.”

In Nigeria’s Niger Delta, where 400,000 barrels of oil are stolen each day, authorities are using AI predictive analytics to pinpoint oil bunkering and where it is likely to occur. The machine learning synchronizes datasets to detect oil theft quickly.

“AI can analyze pipeline flow data and identify irregularities that indicate theft,” wrote Afolabi Ridwan Bello and co-authors in an article published in IRE Journals. “Unlike conventional pressure sensors, AI algorithms can detect even small leaks or slow siphoning attempts.”

Another innovation in its early stages is the use of autonomous sensor networks. These systems of connected sensors are deployed from a range of platforms including buoys, onshore stations, drones, and vessels above and below water. These networks can be particularly valuable in alerting authorities of activity from uncrewed underwater drones.

Breaking Barriers to Share Information

To make the best use of the data they collect, African countries are working to overcome historical barriers of mistrust. These barriers exist between countries and between private companies and national authorities. The mistrust causes countries to avoid sharing vital information about ships crossing borders.

“The pursuit of MDA and the bringing into operation of [information sharing centers] is imperiled as long as there continues to be a ‘culture of secrecy,’” wrote Timothy Walker for the Pretoria-based Institute for Security Studies (ISS). “The practice of making information freely and openly available is frequently discouraged by states, shipping organizations and shipping companies as many fear that it will lead to interference with and the disruption of the principle of freedom of navigation.”

One positive development has been the creation of maritime rescue coordination centers that share data to help search and rescue operations. There are now five regional centers and 26 subcenters covering the entire African coastline.

Other data-sharing initiatives have taken shape with the help of the regional economic communities. In West Africa, the signatory countries of the Yaoundé Code of Conduct have created the Yaoundé Architecture Regional Information System. This platform connects 27 maritime centers to share data about events within 6,000 kilometers of the West African coast. The system, operational since 2020, has led to high-profile interceptions of hijacked vessels, allowing for a coordinated response across multiple countries.

Naval leaders also credit annual maritime exercises such as Obangame Express in West Africa and Cutlass Express in the Indian Ocean with building trust and enhancing information sharing. At Obangame Express, information is shared from national maritime operations centers up through multinational centers, regional centers and on to the Interregional Coordination Center in Yaoundé, Cameroon.

“Exercises like Obangame Express are an opportunity to test some pillars of the regional maritime security and safety strategy for the Gulf of Guinea, notably the exchange of information, the harmonization of operational procedures and the strengthening of cooperation between partners in the maritime sector,” said Capt. Emmanuel Bell Bell, head of the Information and Communication Management Division at the Interregional Coordination Center.

Broadly speaking, experts see countries breaking down barriers and showing a greater willingness to cooperate.

“I’m seeing an improvement that states are much better in sharing this information, not just among themselves, but also engaging with international partners and international organizations like Interpol,” Denys Reva, a maritime security expert for the ISS, told ADF. “The ability has improved, and there is much more political will from African states to share information and engage with each other.”