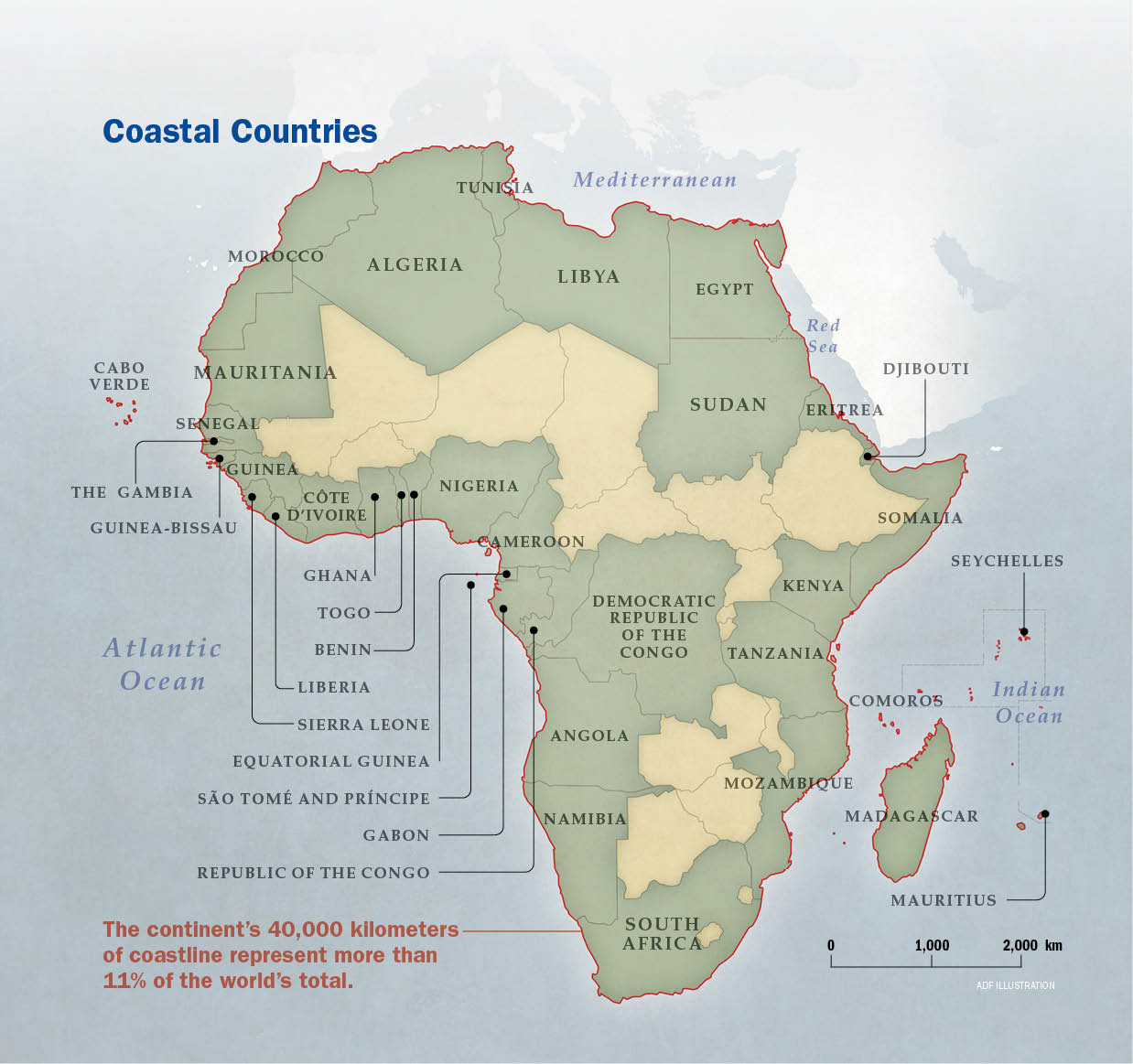

Africa has a vast and resource-rich coastline, but its 37 coastal nations often struggle to find the resources to patrol and protect it.

The continent’s coastline, which stretches 40,000 kilometers, represents more than 11% of the world’s total. The Atlantic Ocean, the Gulf of Guinea, the Western Indian Ocean and the Red Sea are rich in natural resources and offer critical pathways in global shipping. But its marine access also is a security problem, with criminals taking advantage of its expanses. Robbery, hijacking and piracy disrupt shipping lanes and threaten global trade. Illegal fishing devastates coastal economies, depletes fish stocks and even destroys ocean beds. Smuggling and trafficking of drugs, weapons, and people undermine personal, national and corporate security.

Even for countries with large navies, such as several in North Africa, maritime crime is a problem. In other parts of Africa, economic powerhouses such as South Africa and Nigeria struggle to adequately finance national navies and coast guards.

Researchers say many African nations, in constructing their military budgets over the years, have had to put most of their resources in their armies at the expense of their navies and coast guards.

“As African countries and foreign interests seek to unlock the full potential of the ocean economy, they’re contending with criminals similarly competing for this geostrategic ocean space,” wrote Carina Bruwer, a senior researcher at the Institute for Security Studies in Pretoria, South Africa. “These actors equally benefit from increased maritime trade and technological developments that make vessels bigger, faster and able to travel longer distances.”

Bruwer told ADF that Africa’s combination of a wealth of marine resources and a lack of maritime security assets have been made worse by weak governments and high levels of corruption and bribery.

One example, she said, was the rise in Somali piracy in the Horn of Africa, which became a global concern in about 2011. Among other things, researchers blamed a fractured security environment in which countries did not work together or share maritime domain information. It forced navies and other groups to come together in what many said was an unprecedented response to protect their countries’ shipping routes. The result was the near elimination of piracy for a time.

In recent years, the number of incidents has been relatively stable, with the International Maritime Bureau’s Piracy Reporting Centre noting that global piracy decreased by 3% in 2024 compared to 2023. But reports of Somali piracy, for the first time since 2017, are again raising concerns.

Bruwer said the region’s initial weak responses to piracy exposed the shortcomings of their resources and procedures.

“It’s one thing to criminalize piracy, but then you need the ability to actually capture them,” she said. “Then you need the ability and the capacity to successfully prosecute them. You may intercept drug traffickers in your own waters, but when you have a vessel suspected of piracy 200 nautical miles from the coast, it is actually very difficult to prove.”

Many of Africa’s navies and coast guards are spread too thin, she said.

A shortage of security resources is a common theme throughout coastal countries. That was clear in mid-May 2025, when terrorists attacked a marine research ship off the coast of Cabo Delgado province in northern Mozambique.

The Mozambican Navy is charged with protecting a 2,500-kilometer coastline that stretches along the Indian Ocean from Tanzania in the north to South Africa in the south. It is estimated that the country has fewer than 20 operational patrol vessels. In the terrorist attack, the ship was researching Mozambique’s fisheries resources, according to the Centre for Public Integrity. When two nearby speedboats began firing at them, the ship’s crew retreated to the high seas. They immediately contacted the Mozambican Navy for help, “but that help did not arrive,” one witness told the Club of Mozambique news site.

The attackers eventually gave up because of rough seas and pulled away. The researchers since have said there was no excuse for officials’ failure to respond to their calls for help. Weeks after the complaints, Mozambican officials said they still were looking into the incident.

POOLING RESOURCES

Researchers say there are ways to share resources to address transboundary issues, even on a limited basis. Cost-effective resource sharing includes pooling information and intelligence, joint operations and patrols, and integrating legal frameworks and standard operating procedures. Some organizations and tools already are in place to help.

The Yaoundé Code of Conduct, which was signed by 25 West and Central African countries in 2013. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) says the code’s primary objective is to manage and reduce harm “derived from piracy, armed robbery against ships and other illicit maritime activities, such as illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing.”

The code emphasizes collaboration among Gulf of Guinea countries and focuses on national maritime security and contingency plans.

The Africa Center for Strategic Studies says the Yaoundé Code has become “a model for how to do maritime cooperation at the regional level.”

“Countries of the Gulf of Guinea work together to address their common challenges and there is a ‘culture of collaboration,’” the Africa Center said in 2023. “The creation of trust among participants is the code of conduct’s greatest accomplishment. Another important lesson is that a small, motivated community of practitioners can have an impact.”

The Africa Center noted that the code still was a work in progress, saying, “The Yaoundé architecture works, but not optimally or equally across all of the zones.” The Africa Center said there still were issues with coordination and information sharing, and that not all of the member nations had created national maritime strategies or funded them adequately.

The Djibouti Code of Conduct, established in 2009, focuses on combating piracy and armed robbery, specifically in the Western Indian Ocean and the Gulf of Aden. The Djibouti Code promotes intelligence sharing, joint patrols and capacity building. There are 20 member countries, including Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. The IMO said member countries have agreed to the following:

The Djibouti Code of Conduct, established in 2009, focuses on combating piracy and armed robbery, specifically in the Western Indian Ocean and the Gulf of Aden. The Djibouti Code promotes intelligence sharing, joint patrols and capacity building. There are 20 member countries, including Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. The IMO said member countries have agreed to the following:

The investigation, arrest and prosecution of people who are “reasonably suspected” of having committed acts of piracy and armed robbery against ships, including those inciting or planning such attacks.

The interception and seizure of suspect ships and property on board.

The rescue of ships, people and property subject to piracy and armed robbery, including the proper care and treatment of such victims as fishermen, other shipboard personnel and passengers.

The conducting of shared operations among member countries and with navies from countries outside the region.

In 2017, officials added the Jeddah Amendment, which expanded the code to include human trafficking and other illegal maritime activities in the western Indian Ocean and the Gulf of Aden area. These activities include human trafficking and smuggling; illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing; trafficking in narcotics and psychotropic substances; arms trafficking; illegal trade in wildlife; crude oil theft; and illegal dumping of toxic waste.

The Combined Maritime Forces (CMF) is the world’s largest multinational naval partnership, with 46 member nations, including Djibouti, Egypt, Kenya and Seychelles. The partnership says it is committed to “upholding the rules-based international order at sea, promoting security, stability and prosperity” across 8.3 million square kilometers of international waters, including some of the world’s most important shipping lanes. The CMF’s main focus areas are defeating terrorism, preventing piracy, encouraging regional cooperation and promoting a safe maritime environment.

AFP/GETTY IMAGES

The CMF is testing seagoing drones as a cost-effective means to patrol the seas. It deployed four uncrewed surface vessels, also known as sea drones, on a continuous patrol of the Red Sea for more than 50 days in 2025, a first for the organization. Between February and April, the vessels patrolled a 219,000-square-kilometer operating area — about half of the Red Sea — looking for signs of illicit activity. The U.S. Navy supplied the four sea drones, which maintained a constant, all-weather watch while sharing video feedback and real-time radar with operators at CMF headquarters.

“As well as giving the task force real-time visibility of on-water activity, the deployment produced important observations of maritime traffic that is easily shared with regional partners,” said Royal Australian Navy Capt. Jorge McKee. “Nothing beats having eyes out on the water.”

McKee, who commanded the task force responsible for the mission, said criminals and other nonstate actors “will exploit any gap they can find.”

“The high-seas are shared spaces for the common prosperity of all people, but if nobody is looking we know that smugglers will move drugs and weapons, illegal fishermen will plunder the oceans, and pirates will rob or hijack ships,” McKee said, according to the CMF. “This operation demonstrates the value of extra eyes on the water, and helps us to know where to put warships in the right place to seize illicit cargo, and protect innocent mariners.”

The Regional Coordination Operations Centre (RCOC) in the Seychelles and the Regional Maritime Information Fusion Centre (RMIFC) in Madagascar focus on exchanging maritime information. The centers were established in 2018 to manage information exchanges and sharing, and joint operations at sea. Seven states signed the original partnership agreements: Comoros, Djibouti, France, Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritius and Seychelles.

Working closely with its sister center, the RCOC coordinates regional operations to combat illegal maritime activities with the support of assets contributed by partner nations. The U.S. Navy says the RMIFC “focuses on deepening maritime awareness and facilitating the exchange and sharing of maritime information with national centers and international information fusion centers, while the RCOC uses the information provided by the fusion center to initiate and coordinate operations at sea.”

Authorities displayed that coordination in January 2023 when they seized 3,000 rifles, hundreds of rounds of ammunition and anti-tank missiles from a fishing vessel in the Gulf of Oman. The Iranian weapons were destined for the Houthi militia in Yemen. Days earlier, officials intercepted 2,000 assorted Iranian weapons on a fishing ship bound for Yemen.

Without vessel information the RMIFC shared with local authorities, some of the weapons might have wound up in Somalia and sold to terrorist groups such as al-Shabaab and the Islamic State group in Somalia. The RMIFC fights weapons trafficking by sharing and exchanging maritime security information on ships suspected of committing crimes.

The center helps identify ships suspected of weapons trafficking and other sea crimes, such as drug smuggling, illegal human migration and illegal fishing. Constant monitoring by the center’s watch room helps it quickly warn maritime law enforcement agencies of threats.

A UNIFIED RESPONSE

Bruwer and others have pointed to a lack of political will, along with problems of coordinating multiple navies and bureaucracies, as barriers to cooperation. There are issues of overlapping jurisdictions, weak legal systems and a lack of proper interaction among agencies.

The Africa Center and other organizations have pointed out the need for balancing national sovereignty with regional cooperation, requiring a standardization of laws and trust-building. Many countries have incomplete chains of prosecution, from arrest to conviction.

Researchers say Africa’s coastal nations must prioritize acquisition and maintenance of patrol boats and surveillance equipment. They will need to emphasize training and retention of maritime military and law enforcement personnel. They will have to advance their maritime infrastructure, including communication networks.

But there remains the glaring problem of too much territory to patrol and protect but too few resources.

“We know we often use this cooperation rhetoric, and everyone is keen to cooperate,” Bruwer said. “But there is very limited ability to do that. It’s great if you say that we will assist our neighboring country to counter maritime crime, but it’s difficult to actually allocate patrol resources.”

Each country needs a government department to “really champion” maritime security to make sure it is a priority “and therefore well-funded,” Bruwer said. She added that sharing capacities and information to collectively safeguard Africa’s shores is “nonnegotiable.”