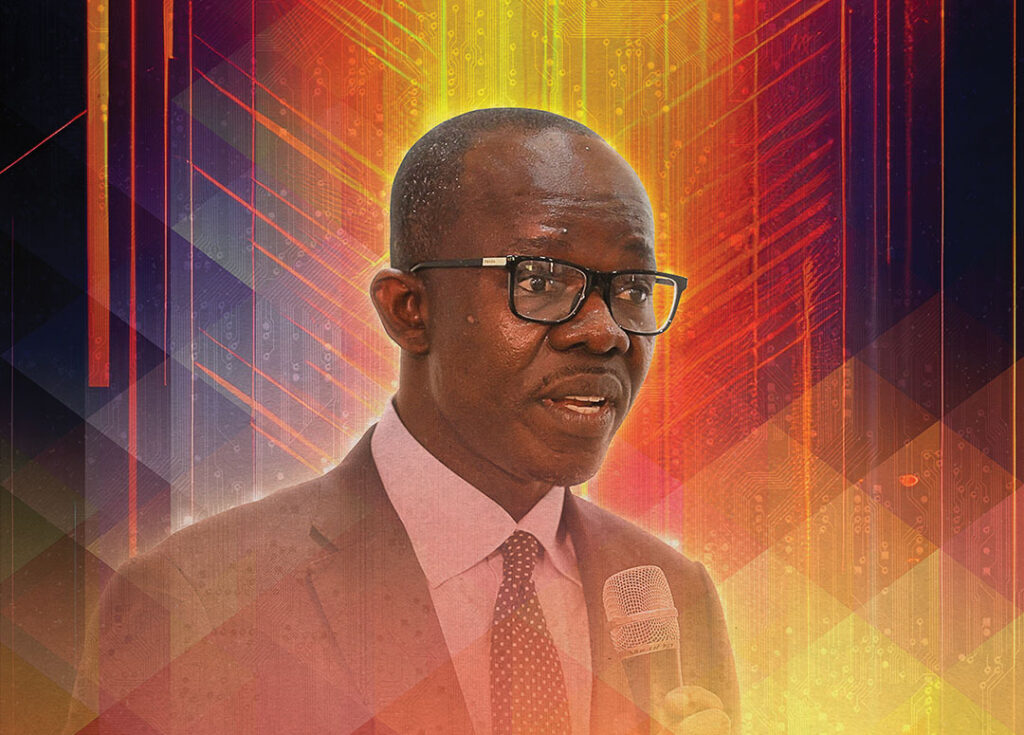

Dr. Antwi-Boasiako is a cybersecurity expert who has worked in the public and private sectors for more than a decade. In 2011, he founded eCrime Bureau, West Africa’s first digital forensics firm. He served as a cybersecurity expert with the Interpol Global Cybercrime Expert Group and with the Council of Europe’s Global Action on Cybercrime Extended Project. In 2017, he was named Ghana’s National Cybersecurity Advisor and head of the National Cyber Security Centre. In this position, he helped craft Ghana’s Cybersecurity Act, which was passed in 2020. In 2021, he was named director-general of Ghana’s Cyber Security Authority, a post he held until 2025. He spoke to ADF from his office in Accra. His remarks have been edited for length and clarity.

ADF: Looking at the cyber landscape in West Africa today, how would you describe the threats from state actors and nonstate actors? How vulnerable are governmental institutions and critical infrastructure?

Antwi-Boasiako: When I look back 10 years, the cyber threats that were facing the region were social-engineering attacks. These are the usual type of scams like romantic fraud and others. Those attacks were more outward in nature. They were emanating from the continent and targeting Europeans and Americans. That is when the 419 [“Nigerian prince”] scams and the Sakawa [spiritualism] scams were prevalent. But today the trend has changed. I’m happy you mentioned the risks faced by critical information infrastructure: government databases, critical systems. There is a great deal of digital transformation going on within the continent, and Ghana is one of the countries adopting a number of digital transformation initiatives: digital ID systems, paperless ports systems, criminal justice administrations using digital platforms.

Within the last few years, we’ve seen a surge in ransomware attacks. Our analysis shows that they are emanating from criminal actors, and the primary motivation is financial gain. Around 80% of attacks that we’ve seen are financially motivated. Money is the main driver for this. But I think we also worry about the role of state actors, either directly by states or by their proxies. Even though Ghana’s geopolitical position has always been nonaligned, as was construed by the first president, Dr. Kwame Nkrumah, increasingly we are anticipating threats that will come from state actors. As a nation, we are in serious preparedness by way of awareness creation, by way of legislation, but also by way of our cyber defenses, to be able to stem the attacks.

CYBER SECURITY AUTHORITY OF GHANA

ADF: In the early 2000s, Ghana had major challenges relating to cybercrime, most notably fraud, blackmail and identity theft. Can you describe how this affected the country and why you and others chose to make combating cybercrime a national priority?

Antwi-Boasiako: The cybercrimes that were being perpetrated were directed outward, but it had an impact here. In that period, we discovered that if you lived in Ghana and you saw something on Amazon or eBay, you couldn’t use your credit card to make a purchase. It had a serious effect on e-commerce adoption. Even as of now, there are limitations on IP addresses coming from regions that are associated with fraud. It is a serious issue, and it affects investment in the country.

I want to share a story. In 2012, 2013, something changed. At the time I was in the private sector, and the worst email business compromise attack occurred, and my firm, the eCrime Bureau, was contracted to investigate. The fraud led to more than 2 million euros that were for infrastructure projects in Ghana being diverted to third-party countries. Government and leaders within the country started realizing that the 419, the Sakawa, the Yahoo Yahoo fraud, the identity theft, those crimes are not just directed at Europeans or Americans, but it’s something that is having an impact on us. And I think that is where some of our response started.

ADF: What was the response?

Antwi-Boasiako: I remember that one of the first conversations we had was for Ghana to accede to the Budapest Convention [an international treaty designed to harmonize global response to cybercrime]. In the case I investigated, money had moved into two different countries, and IP addresses were located on four different continents. The question was, “How do you investigate cross-border crime of this nature?” You need international cooperation, and you need the tools available to be able to engage with different countries. Ghana moved quickly to ratify the Budapest Convention and started creating legislation to enhance the cyber resilience of the country and worked on the protection of children on the internet. It was the proliferation of these crimes and attacks that led to serious government action. I must say it started, to some extent, through what we call awareness creation. Once the attacks were directed inward, then policymakers and political actors began to understand that the issue of cybercrime was not just some young, poor boys who have the skills to defraud and make some money; it has serious consequences.

ADF: You have said that, in Africa, the approach to cybersecurity needs to be more systematic and less ad hoc. What do you mean by that?

Antwi-Boasiako: I think the scale of the problem has necessitated a shift. We need to systematize the process. Certain imperatives need to be addressed: policy, strategy, establishing institutional framework, and that is why the Cyber Security Authority in Ghana was established. A few African countries are doing the same. Ghana leads the African Network of Cybersecurity Authorities, and currently we have about 20 countries that have dedicated agencies responsible for cybersecurity issues.

ADF: Ghana also has established a Computer Incident Response Team, or CIRT. Can you describe what this team does and how it helps defend the country against cyberattacks?

Antwi-Boasiako: Despite the efforts we’ve put in place, one day an attack will happen. It’s a matter of when, not if. Therefore, having an efficient CIRT system is imperative. Ghana has adopted what we call a decentralized CIRT system in which we have a national CIRT and other sectoral CIRTs. The banking sector, financial techs, insurance, all the financial-related entities are grouped under a sectoral CIRT. The Bank of Ghana is our lead in that particular area. What it means is incidents are coordinated within the sector, then they work closely with the national CIRT.

We have another CIRT for government databases, another one with the telecommunications, another one for national security. That is how our setup is in terms of the CIRT ecosystem as a country. There are different models, depending on how the internal government structure works, but we had to adopt this because there are quite a number of strong regulatory bodies that we believe, if we work through them, we can better achieve compliance.

GHANA ARMED FORCES

ADF: You have said only about 35% to 40% of Ghanaians have basic cyber awareness. Why is this dangerous and how can it be improved?

Antwi-Boasiako: I think if you ask me now, I may even revise that number because [35% to 40%] may be ambitious. Awareness creation of cyber risks is the biggest issue. The gap between the citizens’ use of digital devices and their awareness of cyber risks keeps on widening. Especially now when you have AI-enabled tricks being used. You’ve got videos and images being manipulated using AI systems, and the citizens are actually helpless. Even sometimes to a dedicated eye, it has become quite difficult to distinguish between what is authentic and what is not. There is this growing fear that as technology evolves, the awareness level of our citizens becomes quite low. That is having a huge impact.

One of the things we do every year is National Cyber Awareness Month, through which we engage the citizens as much as possible. We also use social media platforms to issue security alerts when we see a common trend, because the low-level crimes are also organized crime. You have scammers sometimes who put themselves in one apartment and their job is just to be scamming and making money. The funds are little, but the aggregate volume is quite huge. The cumulative effects as far as losses by citizens are significant.

We try to share information and create awareness and educate the public, but I must say there are still some gaps that we need to cover. We need to reach out to our citizens who may not be able to read English. In Ghana, financial inclusion has a high penetration. In remote villages, they are all using mobile money transactions. They are all potential targets. Even my old mom in the village is a potential target for fraudsters.

ADF: Each year, during National Cyber Security Awareness Month, the Ghana Armed Forces holds events for its personnel. What role do you think the military can and should play in supporting cybersecurity?

Antwi-Boasiako: The military’s role in terms of incident response is very much consistent with the mandate of a typical military. What is the military’s role? To deal with the territorial integrity and national defense of the country. Certainly the military’s role is to protect their internal systems because that is a potential target for an enemy. Cyber defense, in my view, is both defensive and offensive. That is one area that is a work in progress. I think the road map is, as you modernize your military and you introduce more network-centric systems to make your military efficient and technology compliant, then your internal defense also needs to be strengthened.

ADF: Today, the continent has an estimated 20,000 trained cybersecurity professionals, which is about one-fifth of the total needed, according to the cybersecurity firm CrowdStrike. What needs to be done to expand training and employment opportunities for young cybersecurity professionals?

Antwi-Boasiako: That’s a big issue, the issue of skill sets. Government needs cybersecurity professionals to protect the country, the private sector needs them, criminal justice needs them. The education system needs lecturers to impart knowledge and skills to the new generation of professionals being produced at our universities. The needs are there. What Ghana has started is we introduced what we call the accreditation system, which is basically registering cybersecurity professionals at three levels and at a general category as well. On one hand, we have certain professionals who studied and worked abroad and have returned home. These guys are quite good; they have exposure, they have experience, but they’re quite expensive. The strategy has been to get one or two or three of them and then you can get younger ones who are quite talented coming from our universities, and they can understudy.

The registration is helping us to identify those at the bottom so that you’ll be able to possibly have a policy to have the senior ones, the most qualified ones, be able to support them by work training. That is one area that we have started to deal with: workforce development. I think broadly the plan is to have research to determine which skill sets we have and how many are needed. That is one area we are also looking at to ensure that we develop the necessary skill sets. We need to have the numbers and know how many we have in the system. Without that, it is very difficult to determine how many more you want to add.

ADF: In 2024, Ghana was rated as a Tier 1 nation for cybersecurity on the Global Cybersecurity Index, the highest tier. It was the second-highest rated African nation, with a cumulative score of 99%. What are your goals for the future, and where would you like to see Ghana improve?

Antwi-Boasiako: I think you made it a personal question so I’ll answer personally. I’m proud to see a developing country start this journey from nowhere. In 2017, when I was appointed, the [International Telecommunication Union’s Global Cybersecurity Index] level was about 32%. And by 2024, the percentage jump was quite impressive [to 99%]. I must say the political commitment is the denominator. We’ve been lucky to have that political commitment to drive us. We’ve also been lucky to have a team of technical people and educated staff who have helped us achieve this milestone.

I think it’s impressive to tell the story that you may be a developing country –– and Ghana is not a rich country –– but I think that shared determination and focus has really put us in a serious position. I’m proud to say that a few things that we have introduced here, other countries are now learning from that: license and accreditation. We have other Western countries talking to us to learn how we did that, protection of critical information infrastructure, protection of children on the internet. When I say I’m proud, it’s because we are a net contributor to cybersecurity development by way of best practices. It was a proud achievement.

The next coming years I do expect the same political commitment to continue, I do expect the same spirit of focus and drive. Look, the country is digitalizing. We don’t have options; we don’t have excuses. We must develop our cyber competency and cybersecurity systems to be able to defend the investments we are making.

ADF: You recently published a book titled “Ten Commandments for Sustainable National Cybersecurity Development.” Why did you think it was important to write this book, and what do you hope readers take away from it?

Antwi-Boasiako: The book was written for the general audience. It’s not technical; it’s an easy read. That’s the feedback I’m getting. A nation’s cybersecurity development is a multidimensional undertaking. It is wrong if we just think of it as a technical undertaking. You need all the facets of society to be involved. You need civil society, you need criminal justice, you need national defense, you need the business community, industry, you need international partners. In communicating, you need to have a language that is common to all. The motivation was driven by my own experience. I’ve seen that African countries are making strides; there are some initiatives. But the problem was that they are not integrated; they were not programmed in a manner that can have a collective impact. Coordination was absent and, in some cases, there was duplication. We need a guiding principle, so that’s why I used the phrase “Ten Commandments.” These are 10 areas that anyone who picks up the book, no matter their position, they can play a role. And I use the word “commandment” because each of these are an imperative; they are a must do.