ADF STAFF

Six of every seven COVID-19 cases in Africa go undetected, according to a report by the Africa regional office of the World Health Organization (WHO).

The low detection rate — 14.2% — has complicated the continent’s ability to find and respond to outbreaks before they become full-blown infection waves, said Dr. Matshidiso Moeti, director of WHO Africa based in Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo.

“With limited testing, we’re still flying blind in far too many communities in Africa,” Moeti said during a recent press briefing.

Most of the 75.6 million tests conducted on the continent so far have been on people already showing COVID-19 symptoms.

“But much of the transmission is driven by asymptomatic people, so what we see could just be the tip of the iceberg,” Moeti said.

Moeti’s office reached its conclusion about missing COVID-19 cases using a calculation produced by the global public health group Vital Strategies. The calculation uses statistics such as known infections, deaths and fatality rates to estimate the number of undetected cases.

By that calculation, Africa’s true COVID-19 caseload is more than 59.6 million. The official estimate published by the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) was just under 8.5 million cases in late October.

Based solely on official counts, Africa has escaped the worst of the pandemic compared to other parts of the world. But the new WHO Africa estimate aligns with other research showing that that might not be the case.

Estimates of excess deaths since the beginning of the pandemic suggest the true death count on the continent could be up to four times higher than official tallies. A study by a South African insurance provider estimates that up to 80% of residents of that country have been exposed to COVID-19.

The WHO and Africa CDC have begun working to dramatically expand testing of Africa’s 1.3 billion residents to find COVID-19 hot spots and snuff them out before they become infernos of infection.

Key to the program is a plan to deploy tens of thousands of rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) across the continent. The simple, inexpensive RDTs provide results in about 15 minutes.

“Health care workers are able to use RDTs regardless of their level of skill,” Moeti said.

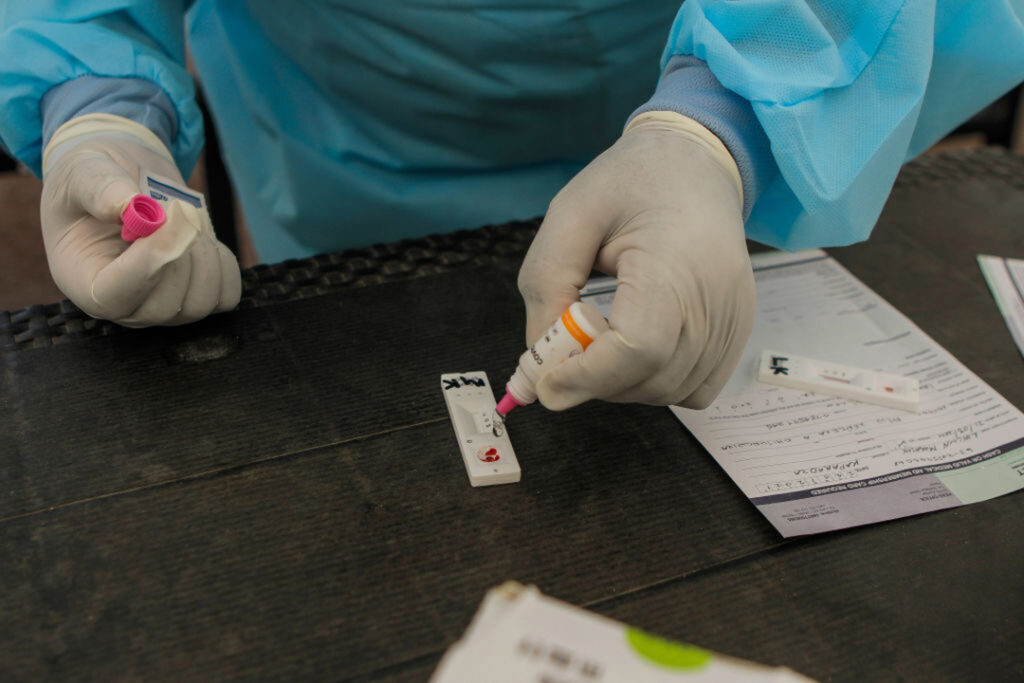

To take an RDT, a health worker uses a nasal swab to collect a sample, which is then applied to a testing strip and treated with liquid reagents to produce a result.

RDTs reveal antigens, the proteins associated with the virus that provoke an immune response. The tests are recommended for people who experience early symptoms or who have recently been exposed to an infected person.

RDTs are less sophisticated than lab-based PCR (polymerase chain reaction) tests, which identify the virus’s specific genetic material. PCR tests are more precise, but also more expensive and take days instead of minutes to produce results.

Moeti compared the COVID-19 testing project to the effort to break the 2014-2016 Ebola epidemic in West Africa.

In that case, public health officials developed a ring vaccination program to interrupt the spread of the deadly virus. Everyone who lived within 100 meters of a detected Ebola case was vaccinated against the disease.

Using that same approach, Moeti said, public health leaders propose to test people and lock down homes within 100 meters of detected COVID-19 cases. Those in lockdown will receive masks, sanitation supplies and other assistance.

As public health officials deploy rapid tests, they face an important hurdle: public resistance.

The poor quality of earlier COVID-19 RDTs caused many people to mistrust them, giving Africa a testing rate much lower than the rest of the world, according to epidemiologist Dr. Ngozi Erondu, a global health security expert at the policy institute Chatham House in London.

New tests don’t have the problem their predecessors had, Erondu said.

The WHO has approved two RDTs because of their high level of reliability. Using RDTs will help health officials craft targeted lockdowns and avoid the kind of communitywide lockdowns that were so disruptive to economies early in the pandemic, Erondu said.

“RDTs help communities get on top of COVID by providing more data for local decision-making,” Erondu said. “Testing more people tells us where the virus has gotten to.”