ADF STAFF

Australia’s national science agency and Microsoft have joined forces to combat illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing.

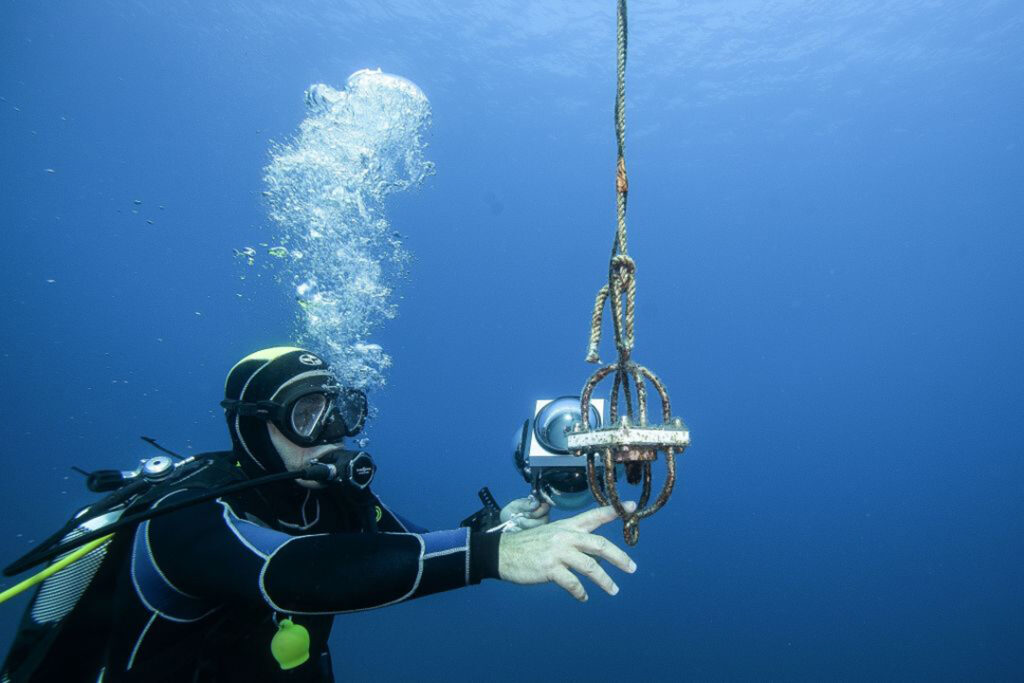

The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) and the technology company are linking artificial and human intelligence by using robotic underwater cameras and sound-detecting technology known as hydrophones to alert authorities of suspicious sea activity around Indonesia and the Great Barrier Reef.

The high-resolution cameras can capture a vessel’s type and features, where it has traveled, the direction in which it is moving and how fast. Hydrophones can record sounds from vessel engines, air compressors and winches, and explosives used in blast fishing — using dynamite or other explosives to stun or kill fish — from tens of kilometers away.

A complementary project in Chile uses information gleaned from fisheries officials through detailed surveys to estimate the scope and characteristics of IUU fishing.

“Illegal fishing is the third most lucrative international crime behind weapons running and drug smuggling,” Chris Wilcox, CSIRO’s chief research scientist, said on the agency’s website. “It affects about a third of the fish in the market and the livelihoods of 120 million people worldwide. So it’s a major problem.”

Using artificial intelligence (AI) to combat IUU fishing likely is the wave of the future, Ian Ralby, a maritime security expert who has written extensively on fishing issues, told ADF.

“It is one of the few ways to harness and assimilate lots of different data sets,” said Ralby, chief executive officer of I.R. Consilium. “You can see what a vessel is doing and its history, not just its movement history, but who used to own it, who owns it now, where [the] owner [is] located, who the beneficial owner is, who the operators are, who used to be the operators, where [it was previously] flagged and what it used to be called.”

Such information could be particularly useful for African nations, which lose an estimated $10 billion annually to IUU fishing, according to the Ocean Science Foundation.

The problem is especially acute in West Africa, where countries have lost about $2.3 billion annually, according to the United Nations. Illegal fishing tactics — such as dragging huge nets along the sea floor, fishing in prohibited areas and turning off a vessel’s automatic identification system to avoid detection — have allowed foreign fleets to decimate the region’s fish stocks, damage the environment and deprive locals of food.

Using AI to counter illegal fishing is not yet widely practiced in Africa.

Although CSIRO touts its innovations as cost-effective, Ralby says that notion may not be shared by authorities in developing countries.

“When your director of fisheries is making 60 euros a month and there isn’t enough money in the agency to purchase the fuel to drive to where there is a port or landing site, this is a different level of cost-effectiveness,” Ralby said.

He added that countries also must have the proper legal mechanisms in place before they can fully realize AI’s potential to counter illegal fishing.

“Many countries around the world — and not just in Africa — do not have the evidentiary laws in place to leverage that level of technology,” Ralby said. “The speed of legislative change in the world is a lot slower than many would like.”