ADF STAFF

The water level behind the Grand Ethiopia Renaissance Dam (GERD) rose again in July, and tensions between Ethiopia and its downstream neighbors rose along with it.

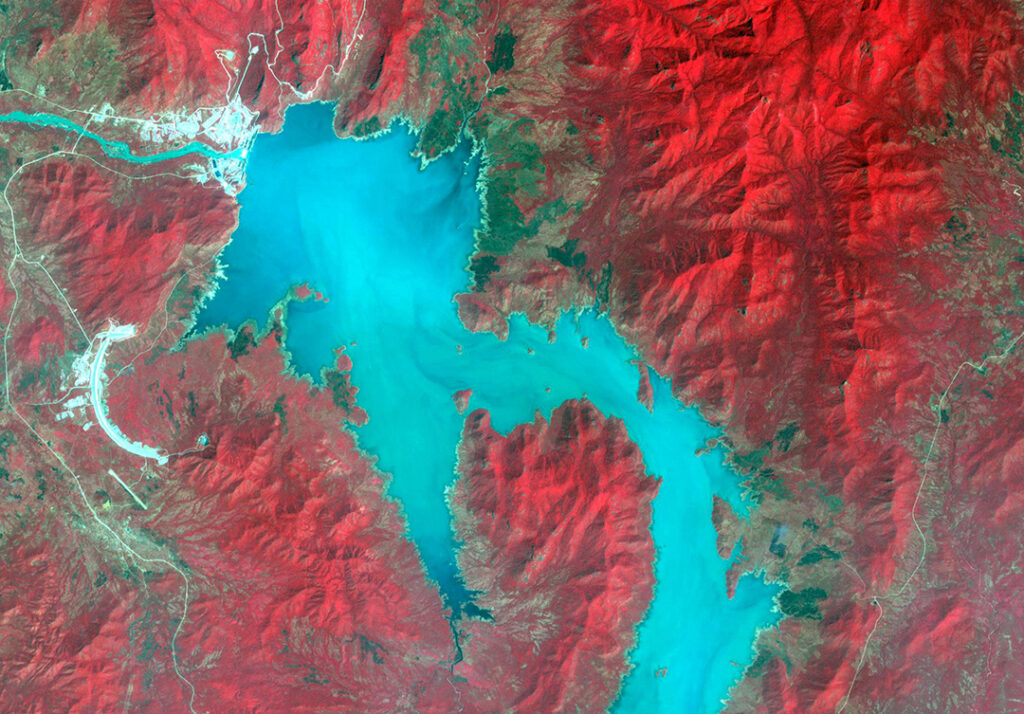

Ethiopia announced on July 20 that it had completed the second filling of the massive hydroelectric dam on the Blue Nile just south of the border with Sudan.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed made the announcement, adding that the filling “will not harm downstream countries.”

Ahmed’s statement did little to appease Sudan and Egypt, who see the Ethiopian project as a threat to their access to freshwater.

“What Ethiopia is doing is an aggression and a clear threat to the Egyptian and Sudanese national securities,” former Egyptian Minister of Irrigation Mohammed Nasr Allam told Al-Monitor. “The problem is not in filling the dam, but rather in the lack of an agreement that meets the interests of all parties.”

In the 2015 Declaration of Principles regarding the dam, Ethiopia agreed, among other things, to avoid causing significant harm to its downstream neighbors. Beyond that, however, the three countries have failed repeatedly to reach an agreement on the management of the dam and its downstream flow, particularly during dry periods.

Ethiopia says it has a right to use the water on its territory as it sees fit — in this case to generate electricity to drive development, lift its citizens out of poverty and provide food security. Less than half of Ethiopia’s citizens have access to reliable electricity, according to the World Bank.

The goal of the second fill is to have enough water to run two electricity-generating turbines. Sudan sought to buy 1,000 megawatts of electricity from Ethiopia in early August. It’s not clear if that electricity will come from the GERD. Sudan already gets 200 megawatts, about 10% of its electrical supply, from Ethiopia.

Egypt, which gets nearly all its fresh water from the Nile, says the dam threatens the stability of its water supplies and, by extension, its future.

Egypt and Sudan both lower their own water reserves during the rainy season to accommodate higher water levels on the Nile. Should Ethiopia unilaterally release water from the dam to generate electricity, the resulting additional flow could damage structures or cause flooding downstream, according to Allam.

He suggested to Al-Monitor that recent flooding in Sudan is connected to the filling of the dam.

“The GERD encapsulates the conflicting narratives … related to water usage, security, and energy in Ethiopia, Egypt, Sudan and the wider Horn of Africa,” Gabonese diplomat Parfait Onanga-Ayanga, the United Nations special envoy for the Horn of Africa, said in a report to the U.N.

The dam is about 80% complete and expected to be finished in 2023. Filling the dam could take up to four more years after construction ends.

When filled, the dam will be Africa’s largest hydroelectric project, potentially capable of generating more than 5,000 megawatts of electricity, more than doubling the country’s capacity.

The African Union continues to seek a solution, with current chair Felix Tshisekedi, president of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, taking over mediation duties from former AU chair South African President Cyril Ramaphosa.

Despite both virtual ministerial meetings and shuttle diplomacy by Tshisekedi, the parties remain at loggerheads.

“Clearly, more needs to be done, given that recent negotiations have yielded little progress,” Onanga-Ayanga said.

Ethiopia walked out on a U.S.-brokered agreement last year.

In February, Sudan proposed calling on the AU, United Nations, European Union and United States to help find an acceptable solution. Ethiopia rejected that proposal as well.

In June, the Arab League called upon Ethiopia to stop filling the dam without consulting Egypt and Sudan. Ethiopia refused that request, saying the dam is an African issue that the three countries must resolve themselves.

Onanga-Ayanga urged all parties to continue to seek a fair and peaceful solution to the stalemate.

“Each of the countries sharing the Nile’s water has rights and responsibilities,” he said. “The use and management of this natural resource requires the continued engagement of all nations involved in good faith.”