ADF STAFF

Recent satellite images of West Africa showed a concentration of light blue dots from Mauritania to Gabon. Farther down the coast, more of the clusters appeared around Angola and Namibia.

The dots represented industrial fishing trawlers actively fishing in the areas, where illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing in countries’ exclusive economic zones (EEZ) has existed for decades. The illegal fishing has decimated livelihoods of local fishermen, severely depleted overfished stocks and wreaked environmental havoc.

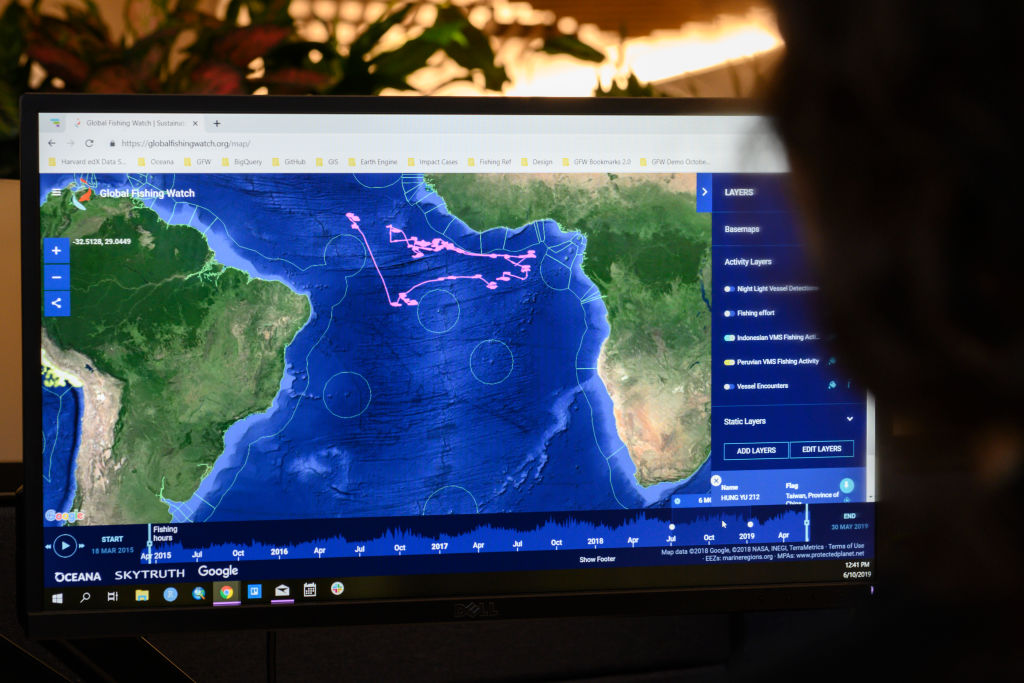

A new study by the University of Delaware used the images produced by vessels’ automatic identification systems (AIS) — and provided by Global Fishing Watch — to assess foreign industrial fishing in coastal African EEZs. Global Fishing Watch tracks fishing through a free, online public map.

The study’s results demonstrate the potential for using AIS and other databases to reveal IUU fishing on the continent, according to Mi-Ling Li of the University of Delaware’s School of Marine Science and Policy and co-author of the study.

“We found fishing vessels from the flag of convenience countries are a large part of fishing activities in African waters,” Li told ADF in an email.

Fishing vessels often fly the flag of a country under which a ship is registered, instead of the country of the ship’s owner, to avoid financial charges or restrictive regulations. Vessels pay registration fees to the countries.

Economists say IUU fishing cost West African countries more than 300,000 artisanal fishing jobs and roughly $2.3 billion in revenue between 2010 and 2016, according to Liberia’s Daily Observer newspaper.

There are drawbacks to relying on satellite data to catch illegal fishers. Vessels involved in IUU fishing often turn off their AIS systems to avoid detection by maritime security forces and fail to dock at local ports, where authorities can inspect their catch.

This activity was observed in Namibia, Li said on the University of Delaware’s website. During the study, AIS data showed 20 fishing vessels in Namibian waters, but some did not report catching any fish there.

“This is a big issue with regards to illegal fishing in African waters,” Li said on the website.

Although China is the world’s worst IUU fishing offender and often targets West Africa, the nation is not alone in its pursuit of African marine life.

The study showed that Japanese trawlers spent most of their time fishing for tuna in East African waters, with 75% of total Japanese catches coming from Madagascar, Mauritius, Mozambique and the Seychelles.

The paper demonstrates how African fisheries are globally connected and highlights the need for “international cooperation to address the challenges that fisheries in the continent are facing,” William Cheung, of the Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries at the University of British Columbia and co-author of the study, said on the University of Delaware’s website.

“We demonstrate the importance of having accessible data, including those from new technology, to generate knowledge that is necessary to address these challenges,” Cheung added.

Although AIS systems have existed for years and are required by law for ships above a certain tonnage, the surveillance ability of many countries and other observers is improving

In March, Sea Shepherd Global used AIS data to track vessels fishing in Sierra Leone’s inshore exclusion zone. The technology helped Sea Shepherd help the Sierra Leonean Navy arrest five trawlers in two days.

Some of the trawlers were fishing without a license and transmitting false electronic identifying information. One of them was using the identity of another vessel fishing more than 7,000 miles away in the Pacific Ocean.