ADF STAFF | Photos by AFP/Getty Images

Omdurman National Bank (ONB) ranks among Sudan’s largest financial institutions. It has branches across most of the country and was the first Sudanese bank to introduce ATMs. Founded in 1993, the bank sits at the center of an expansive web of companies that reaches into every corner of the national economy, a fact that benefits its largest shareholder, the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF).

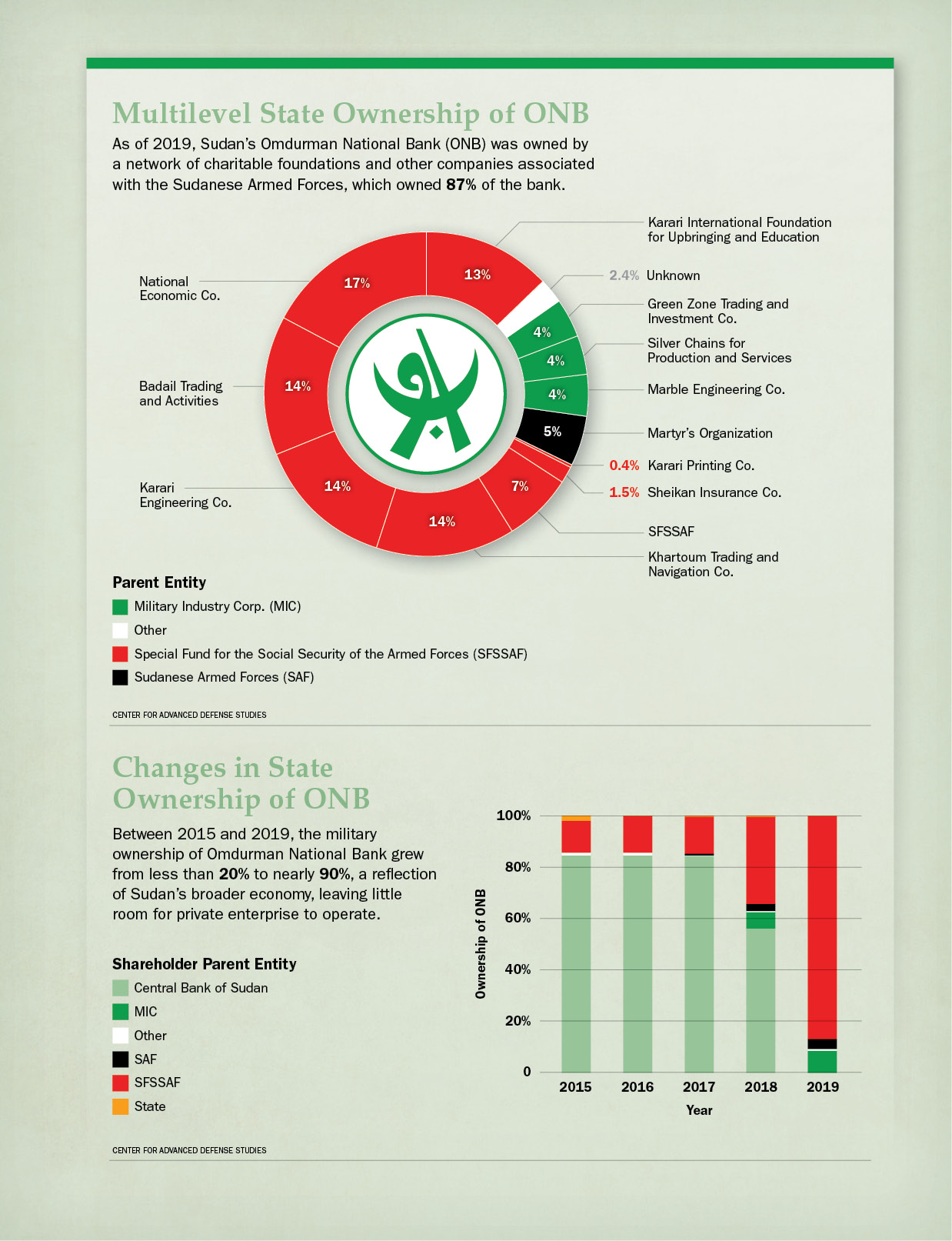

Through a network of military foundations, Sudan’s army covertly owns 87% of ONB, which holds $950 million in assets and is a major force in Sudan’s financial system.

In 2015, the Central Bank of Sudan controlled more than 80% of ONB. By 2019, ownership was almost entirely in the hands of the military, making it a symbol of Sudan’s broader economy. The ONB’s only nonmilitary owner is the Karari International Foundation for Upbringing and Education, a group with close ties to the military.

As fighting continues between the country’s warring generals — Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, leader of the SAF, and Mohamed Hamdan “Hemedti” Dagalo, head of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) — it’s important to examine the system of hundreds of state-controlled enterprises (SCE) that encompasses 85% of Sudan’s economy, according to analyst Samah Salman, who has worked with international companies operating in Sudan.

“It is quite an unbelievable number,” Salman told ADF, noting that under former dictator Omar al-Bashir, Sudan’s security forces accounted for 80% of the national budget.

“That creates no space for the private sector to operate unless you become complicit and play by the rules of the game,” Salman said.

Like the SAF, the RSF has its own bank, Al-Khaleej Bank, that it operates in partnership with the United Arab Emirates to access global financial institutions. Al-Khaleej is Sudan’s second-largest bank by valuation behind ONB. It also is connected to an RSF-linked company called GSK Advance that was the target of international sanctions in September 2023.

Experts say the military’s involvement in business plays a role in the fighting.

“Although it is unclear whether the financial and business interests were responsible for the beginning of the conflict, it is clear that both parties recognize they cannot rule Sudan without power over the economy,” Denise Sprimont-Vasquez, an analyst with the Center for Advanced Defense Studies (C4ADS), told ADF. “Economic control is crucial to rule, and, therefore, neither side is willing to loosen their vise grip on the portions of the economy that they control.”

The scope of the generals’ financial dealings adds an extra dimension to their widening war for power in Sudan. Each side knows that victory will mean an economic windfall.

“They’re both protecting their economic empires,” Salman said. “It’s a winner-take-all scenario.”

Legacy of Tamkeen

Sudan’s current conflict has grown out of the extensive patronage system known as “tamkeen” that al-Bashir created after his 1989 coup against a democratically elected government.

Unlike previous coup leaders, al-Bashir lacked the political authority needed to govern, so he turned to patronage, essentially buying off potential threats by giving military and political leaders increasing power over the economy.

“Al-Bashir was different than other previous dictators in Sudan,” Salman said. “He paid for loyalty.”

The tamkeen system gave security chiefs and al-Bashir’s Islamist allies control over almost every part of public life in Sudan, according to Dr. Willow Berridge of Newcastle University.

The system produced a vast network of companies, such as ONB, that portray themselves as privately owned but actually are SCEs, also known as parastatal companies. C4ADS researchers defined SCEs as companies that are at least 10% in the hands of the government or members of the SAF, RSF or intelligence agencies. That level of control makes them vulnerable to ownership manipulation.

C4ADS researchers identified 408 SCEs based on data provided by the Sudanese Ministry of Finance, the pre-2021 coup Regime Dismantlement Committee and independent investigations. They found that the government conceals its ownership of SCEs as a way of circumventing international sanctions. It “privatizes” SCEs by transferring ownership to nonprofits and other groups that are ultimately controlled by members of the government or those with political connections.

SCE ownership structures show that companies such as ONB and construction conglomerate Zadna International Co. for Investment Ltd. either are controlled directly by the government or indirectly through other companies that the government controls.

“After 2000, government control of SCEs was concealed behind companies within the Military Industry Corporation’s Giad network, on the largest proxies for state ownership,” C4ADS researchers reported. The Military Industry Corp. is a state-owned weapons-maker with its tendrils spread throughout Sudan’s economy, including a stake in ONB through three of its subsidiaries.

Distorting the Market

SCEs’ profits typically go untaxed, starving the government of vital revenue while their activities benefit a cabal of military and government officials. Sudan’s 408 SCEs spread across all sectors of the economy, from agricultural companies such as White Nile Sugar to banking, gold mining, transportation, weapons manufacturing and beyond.

“These parastatal companies sit outside any formal markets,” Salman said. “They form a gray market. They’ve distorted the market in Sudan.”

Canada’s Fraser Institute ranks Sudan 162nd out of 165 countries for economic freedom, placing it alongside Cuba, North Korea, Venezuela and Zimbabwe near the bottom of the global rankings. Sudan also gets a score of 1.67 out of a possible 10 points for the degree to which the military shapes law and policy in the country. The lower the score the greater the military’s influence.

“Pro-democratic civilian control of the economy is a prerequisite for a democratic Sudan,” C4ADS researchers wrote in their analysis.

Sudan’s SCEs exist in a system of vertically integrated monopolies. The system has engendered widespread corruption that undermines private enterprise, experts say. Any private company attempting to do business in Sudan inevitably must take part in the corruption.

C4ADS compiled its database of Sudan’s parastatal companies by tracing the crisscrossing lines of ownership, boards of directors and beneficiaries to create a map of Sudan’s deep state.

“Throughout the thirty years of al-Bashir’s rule, while the economy crumbled, the deep state solidified its control over resources and corporate assets across Sudan’s key sectors,” C4ADS analysts wrote in their 2022 report, “Breaking the Bank.”

The SAF, for example, used its connections to receive letters of credit from banks it controlled and avoid import taxes, giving it an advantage over private companies that could do neither of those things, the C4ADS report notes.

After the RSF’s precursor, the Hemedti-led Janjaweed, conducted a yearslong genocidal assault on the non-Arab population of the Darfur region, al-Bashir rewarded Hemedti with control over Darfur’s Jebel Amir gold mine.

“Hemedti thus became the country’s number one gold trader, smuggler and border guard, and the RSF became the de facto military rulers of northern Darfur,” analyst Alex de Waal wrote in the book “Sudan’s Unfinished Democracy: The Promise and Betrayal of a People’s Revolution.”

After the 2011 split with South Sudan took away much of Sudan’s oil revenue, gold mining became the country’s primary source of hard currency. Hemedti’s control over large chunks of the industry has made the former camel herder one of Sudan’s wealthiest men. Collectively, his family is worth an estimated $9 billion.

“The RSF is a family business with a global footprint,” C4ADS researchers reported.

The revenue Hemedti earns from gold mining, smuggling and hiring out his fighters to other countries has helped him create a sort of state-within-a-state. Through shell companies inside and outside of Sudan, Hemedti also has amassed large amounts of agricultural land.

As the head of the SAF and Sudan’s de facto leader, al-Burhan sits atop a financial network that includes the state-owned Military Industry Corp., along with what remains of Sudan’s oil industry. So far, the fighting between the SAF and RSF has done little to stop the flow of oil from Sudan and through its pipelines from South Sudan.

While Hemedti uses his wealth to fund the 100,000-strong RSF, he remains the primary beneficiary of his network of enterprises. Al-Burhan, on the other hand, is responsible for paying roughly the same number of soldiers along with pensions for military retirees. He also must keep the old al-Bashir patronage flowing to Sudan’s elite.

“Al-Burhan has to protect this large expanse of interest of which he is one beneficiary,” Salman said.

Protecting Their Turf

By some assessments, the military’s deep involvement in Sudan’s economy was the primary motivation for the October 2021 coup that disrupted the country’s planned transition from military to civilian rule. At the heart of that transition, the Regime Dismantlement Committee, known domestically as the Removal of Tamkeen Committee, set about breaking the military’s grip on Sudan’s economy.

While it was active, the committee recovered billions of dollars in illegally acquired assets. It seized more than 50 companies and 60 organizations, more than 420,000 hectares of farmland and 2,000 hectares of residential property, along with hotels, schools, factories and a golf course on the outskirts of Khartoum. The intentional complexity of ownership of some SCEs prevented the committee from breaking them up.

“The dismantling of the military-commercial complex was quietly emerging as [then-Prime Minister Abdalla] Hamdok’s priority agenda, which he would be in a position to push energetically once the military majority on the Sovereign Council was removed,” de Waal wrote in “Sudan’s Unfinished Democracy.”

Against the wishes of Sudan’s military and paramilitary leaders, the committee documented the corrupt networks of businesses. In doing so, “it angered senior military officers by targeting gold-smuggling rings in which they were involved,” de Waal wrote.

The October 25, 2021, coup put a stop to Hamdok’s plan, and the government returned much of the reclaimed properties to their former owners, restoring the status quo despite the wishes of the Sudanese people. The number of SCEs grew sharply after the coup, according to C4ADS.

“Al-Bashir-era cronies and leading military members of the CLTG [Civilian-Led Transitional Government] were opposed to true civilian control of the state all along,” C4ADS researchers wrote. “They knew their grip on Sudan’s economy was paramount to their lasting control.”

As the 2021 coup demonstrated, opening Sudan’s economy, although popular with the public, is not in the interest of Sudan’s military. Neither is a transition to democracy.

“Until the deep state’s economic structures are dismantled, the military will continue to hold all the cards, leaving them no incentive to come to the table and negotiate,” C4ADS researchers reported.

By continuing to corrupt the economy in their favor, al-Burhan, Hemedti and the rest of Sudan’s elite keep themselves wealthy and comfortable while their fellow citizens struggle. Their iron grip on Sudan’s economy also insulates them from accountability.

Al-Burhan and Hemedti both played roles in the genocide in Darfur two decades ago, Salman said. They’re under investigation by the International Criminal Court for the violence that their current war has unleashed in Darfur and around the capital. The loser of the conflict stands to lose more than just his economic empire.

“It’s a very high-stakes situation for both of them,” Salman said. “There’s no incentive for either of them to lay down their arms. It’s a scorched-earth strategy.”

Editor’s note: A quote in an earlier version of this story contained inaccurate information about the location of businesses with ties to the Sudanese military. The quote has been removed.