Operation Lafiya Dole Puts Enduring Peace Within Reach for Northeast Nigeria

ADF STAFF

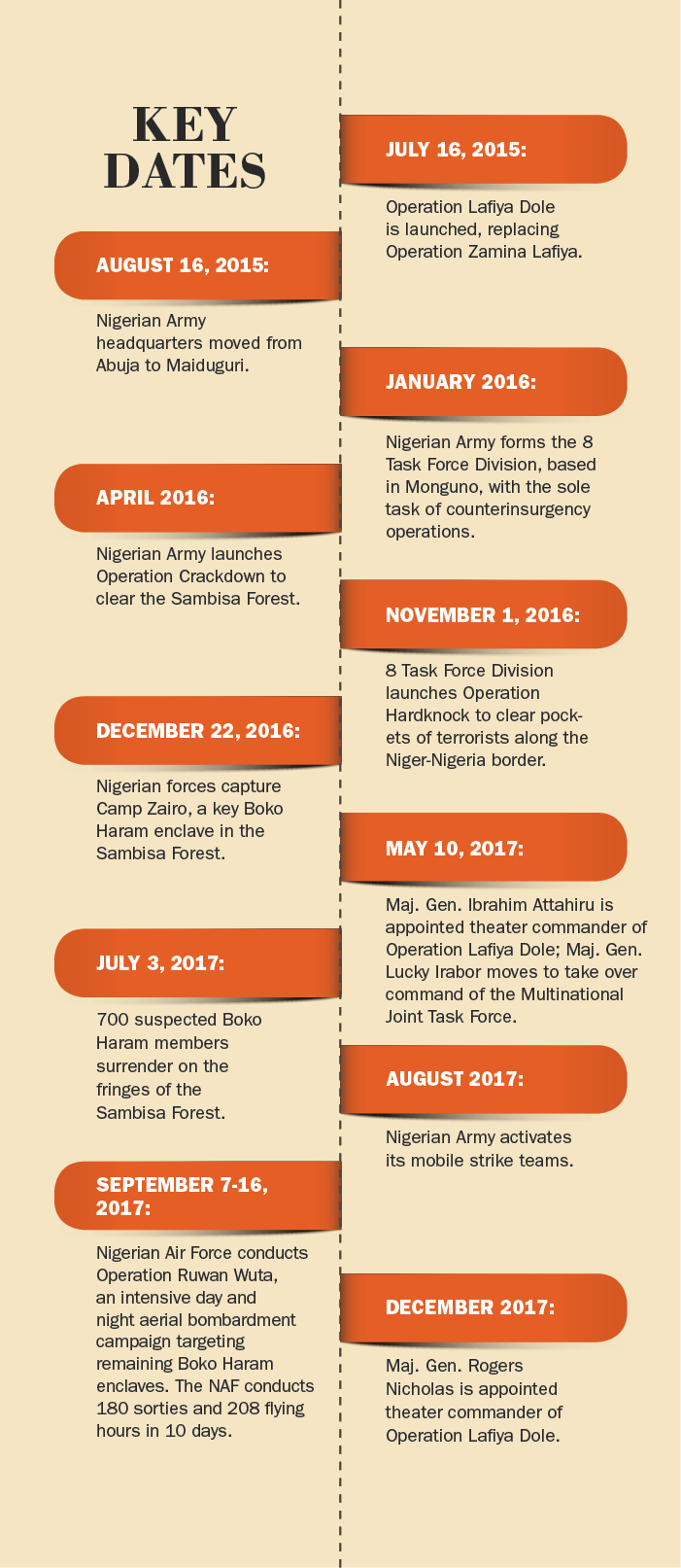

The military operation was as important symbolically as it was strategically. On December 22, 2016, Nigeria’s Armed Forces advanced on “Camp Zairo,” a base deep in the Sambisa Forest that had served as Boko Haram’s nerve center.

The assault began in the early morning with an aerial bombardment. Alpha Jets, F-7 supersonic jets and Mi-35 combat helicopters pounded the camp. After the bombing, ground troops backed by close air support advanced with little resistance and, during a mop-up operation, arrested 1,240 suspected Boko Haram fighters and family members. Thirty other fighters who fled were intercepted by forces from Niger, who were part of the Multinational Joint Task Force operating on the shores of Lake Chad.

The forest redoubt bore the hallmarks of the terror group. Slogans in Arabic were painted on the walls; armored personnel carriers were found burned out, destroyed before a hasty retreat; and troops discovered unmarked graves. Perhaps most significant were the black flags that Boko Haram extremists such as leader Abubakar Shekau had tauntingly displayed in propaganda videos. Nigerian Soldiers took down a flag and presented it to their commander as a symbol of victory.

However, Nigerian Chief of Army Staff Lt. Gen. Tukur Buratai cautioned that the extremist group was dislodged but not eradicated. The fight would go on. “Today Boko Haram are in hiding,” he said. “Tomorrow you wake up, and the spate of attacks seem to continue.”

‘Peace through Force’

Retaking the Sambisa Forest was the signature achievement of the Nigerian military’s Operation Lafiya Dole, which means “peace through force” in the Hausa language.

Launched in July 2015, Lafiya Dole marked a strategic shift in the counterinsurgency effort that was already 4 years old at the time. It aimed to address complaints among front-line troops that they needed help. They said they were underequipped, that decisions took too long, and that corruption was hampering the fight. One of the first changes made by President Muhammadu Buhari when he took office was to move the theater headquarters from Abuja to Maiduguri in the northeast, the epicenter of the insurgency.

In announcing the move, the military said it would “add impetus and renewed vigor” to the fight against Boko Haram.

Observers believe it sent a strong message up the chain of command. “Prior to this relocation there was a major disconnect between those who had a strategic command position in the military and the troops on the ground who were actually confronting the insurgents,” said Dr. Freedom Onuoha, senior lecturer at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. “It was meant to bring them closer to the units on the front line. To feel their pulse and respond to their concerns.”

Nigeria also announced plans to increase its Army personnel strength from 100,000 to more than 200,000 over eight years.

Counterinsurgency

By the time Lafiya Dole was announced, most territory in Nigeria had been retaken from Boko Haram. Between February and May 2015, Nigerian or allied forces liberated 36 Nigerian towns. The phrase “never again” became a popular hashtag on Twitter, with Nigerians vowing that they never again wanted Boko Haram to plant its black flag on Nigerian territory.

The Army needed a new strategy to make that a reality. It followed the traditional military counterinsurgency steps of “clear, hold and build.”

“With over two years of attempting to ‘clear’ Boko Haram from built-up areas, the task at hand now, and one that proved difficult in its own right, was that of ‘hold,’ ” wrote Nigerian military scholar Akali Omeni.

This “hold” strategy required simultaneously securing towns while maintaining the pressure on the outskirts where terrorists lurked. Between late 2015 and mid-2016, the Nigerian Army formed six new brigades. Each was headquartered in a northeastern town and surrounded by three “outfield” battalions roving the rural areas. The garrisoned and outfield battalions had small quick-reaction force (QRF) units attached to them that emphasized mobility and maneuverability over firepower, Omeni wrote. “These units are trained to rely on a [counterinsurgency] action-set, beyond basic infantry tactics,” he wrote. “More than the average Nigerian Army Soldier, therefore, QRF personnel know what to look out for, when out on patrol.”

The goal was to add layers of resistance to insurgents who were intent on asymmetric attacks. The less freedom of movement they had, the more difficult it became to transport supplies and reach vulnerable civilian areas. “Suicide bombers will have more checkpoints to pass through, increasing the risk of detection,” Omeni wrote. “Additional Army patrols, and the retention of police components within outfield battalions will mean IED [improvised explosive device] materials will be more difficult to transport undetected. Added troop numbers in forward areas, along with increased mobility within battalions, means egress for the insurgent will be more difficult.”

There is some evidence that this strategy paid dividends. Boko Haram suicide bombings dropped from an all-time high of 101 in 2015 to 30 attacks in 2016. There was a slight uptick in 2017, but not near the highs of two years earlier.

The Nigerian Army also placed renewed emphasis on “after-action reviews” –– intense analyses following a mission of what worked and what failed. The goal was to quickly react to changing tactics used by Boko Haram. “The man you are fighting is adapting his tactics. For you to stay ahead of him, you must use the aspect of competitive adaptation. That is what we’ve been doing,” Attahiru said.

the Ideological Fight

Boko Haram gained strength, in part, from convincing civilians in the north that they were the victims of a corrupt and illegitimate Nigerian state. Heavy-handed tactics by the military that led to civilian deaths early in the campaign gave this argument some credibility. Even moderate civilians said they felt stuck between two sides they feared. Lafiya Dole sought to change that.

“What we needed to do was to isolate Boko Haram from its support base,” Attahiru said. “Because whether you like it or not, the population can be the support base.”

Beginning in 2014, Nigerian Soldiers participated in town hall meetings and traditional celebrations known as durbars to listen to and respond to the concerns of the people they were protecting. The military also encouraged “census patrols” among lower-ranking officers, including captains, lieutenants and sergeants who were asked to spend time talking to civilians. This not only put a friendly face on the military presence, it helped Soldiers gather information. “Previously, army personnel had been too heavily garrisoned, and what existed as ‘patrols’ were not, in fact, meant to interact with locals,” Omeni wrote. “This new category of interaction … has been vital to the collection of information useful to campaign objectives.”

Furthermore, the Army placed a renewed emphasis on civil-military operations. Efforts included drilling wells for clean drinking water and rebuilding roads and schools. Demining experts used Bozena minesweepers to clear roads in Borno State that had become deathtraps for civilians. On September 19, 2015, Nigerian Army Engineers repaired a bridge linking Maiduguri and Gamboru Ngala, which Boko Haram had destroyed. This vital link reopened commerce between the two cities and improved people’s lives.

Furthermore, the Army placed a renewed emphasis on civil-military operations. Efforts included drilling wells for clean drinking water and rebuilding roads and schools. Demining experts used Bozena minesweepers to clear roads in Borno State that had become deathtraps for civilians. On September 19, 2015, Nigerian Army Engineers repaired a bridge linking Maiduguri and Gamboru Ngala, which Boko Haram had destroyed. This vital link reopened commerce between the two cities and improved people’s lives.

In camps for internally displaced people (IDPs), military doctors treated maladies ranging from malaria to malnutrition, tooth decay to hypertension. In August 2015, IDPs from 13 villages around Konduga and Sambisa went to the 7 Division hospital for treatment.

Attahiru said the Nigerian Army has provided security so nongovernmental organizations and the U.N. can offer job training and other aid to formerly displaced people. The Army also is training local police and civilian defense groups.

“We have a people-centric approach to countering the insurgency,” Attahiru said. “We have respect for local people, and we put their well-being ahead of any other consideration. Insurgents cannot operate without the support — active or passive — of the local population. So by getting the support of the local population, we’ve been able to remove that support for Boko Haram.”

Above all, Lafiya Dole sought to demonstrate the professionalism of the Nigerian Soldier. A Human Rights Desk was set up in the defense headquarters where six lawyers investigate accusations of unethical behavior by Soldiers. A number of high-profile officers, including a former chief of defense staff, have been charged with corruption and faced trial. This signaled to civilians that unprofessional behavior would not be tolerated.

“In terms of what was happening before the launch of the operation, the feeling was that the military had violated some of the rights of the civilian population, which therefore created mistrust,” Onuoha said. “From a professional point of view, the mission was meant to give a banner of a new deployment that would respect the human rights of the people as a way of winning their hearts and minds.”

The Nigerian Army refused to cede ground on the ideological battlefield. It established a Media Campaign Centre to update journalists on Lafiya Dole operations and beefed up its social media presence. It established Lafiya Dole FM, a radio station broadcasting in English, Hausa and Kanuri, that updated the local population on the campaign and dispelled rumors. Finally, the Army heightened psychological operations by using videos, leaflets and even radio jingles designed as outreach to members of Boko Haram who would consider defecting. Operation Safe Corridor and reintegration camps were meant to give fighters a way out. The goal, said Nigeria’s chief of Army staff, was to destroy Boko Haram’s “propaganda machine.”

“We have defeated Boko Haram physically, and we follow them to social media and defeat them as well,” Buratai said.

Attahiru said this holistic approach to counterinsurgency has taken years to learn. He believes Lafiya Dole is now on the right track. “We have been able to identify the drivers of conflict, and we are going to also develop partnerships with local allies,” Attahiru said. “By targeting the drivers of this conflict the whole idea is to break the cycle of violence.”

LAFIYA DOLE BY THE NUMBERS

300,000 hostages and displaced people liberated or given secure housing.

1,009 Boko Haram members surrendered voluntarily.

1,140 Boko Haram members arrested.

1,500 Boko Haram suspects under investigation.

200 Boko Haram camps and enclaves destroyed.

Source: Nigerian chief of Army staff, January 2017