ADF STAFF

Photos by: AFP/GETTY IMAGES

fter Twitter deleted a post by Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari in 2021, Nigeria shut down access to the country’s most popular social media site for seven months.

“The loss was humongous,” Nigerian blogger and social media expert J.J. Omojuwa told ADF. “You got an awakening that this can happen anywhere.”

Internet analyst NetBlocks estimated that the blackout cost Nigerians up to $1.6 billion in lost business. It also disrupted vital COVID-19 information that the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control published on the platform. Human rights groups condemned the blackout as a violation of Nigerians’ right to free expression. In the end, the government restored access, but only after Twitter agreed to pay taxes and set up a local office subject to Nigeria’s laws.

Nigeria’s Twitter blackout belongs to a spectrum of direct and indirect actions intended to control how information is shared. And these information blackouts are becoming more common in Africa. In many cases, the controls are imposed in the name of national security. But the resulting disruptions create less security as they hamstring local economies, interrupt education and drive misinformation.

Along with internet blackouts, censorship efforts in Africa include new laws aimed at cybercrime and campaigns by Chinese and Russian forces to shape Africa’s media environment. Together, they amount to a broad attempt to control the flow of information on the continent.

“When it comes to freedom of expression,” Omojuwa said, “you’re always defending it.”

Internet Shutdowns

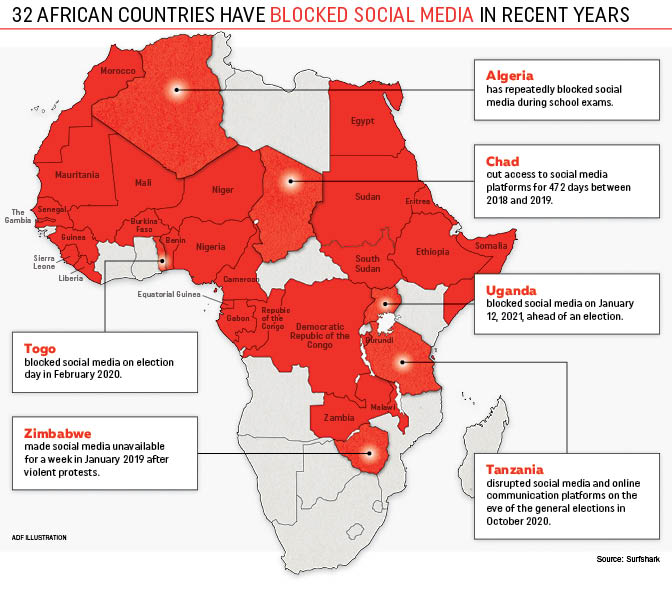

The bluntest instrument that leaders use to censor citizens is the internet shutdown. Africa leads the world in them, according to internet monitor Surfshark. Since 2015, 32 African countries have taken that step to restrict the flow of information within their borders. Between September 2020 and January 2022, African countries accounted for half of the 24 internet disruptions worldwide.

Burkina Faso alone shut down the internet three times between November 2021 and January 2022, including during the coup that toppled President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré.

Coups, anti-government protests and elections are the events most likely to trigger a full or partial blackout. In Algeria and Ethiopia, leaders blocked the internet in 2021 to prevent cheating on national school exams. Ethiopia also has imposed a media blackout to control news relating to the ongoing civil war in the Tigray region.

In some cases, leaders are most intent on throttling social media use. There’s a clear reason for that, according to Lawrence Muthoga, former community engagement manager for Kenya-based Microsoft 4Afrika.

“It’s because it’s very easy to mobilize people on social media,” Muthoga said during a discussion on African censorship hosted by Kenya’s Moringa Group via Twitter Spaces.

“Most of the censorship that’s happening across the continent as we speak is tied to controlling mobilization of people or the spread of ideas,” Muthoga said.

Omojuwa sees another force at work: the generation gap between Africa’s leaders and their young, tech-savvy citizens. Africa’s median age is just under 20 years old. “They [leaders] don’t understand these spaces,” Omojuwa said.

Omojuwa sees another force at work: the generation gap between Africa’s leaders and their young, tech-savvy citizens. Africa’s median age is just under 20 years old. “They [leaders] don’t understand these spaces,” Omojuwa said.

Shutting down the internet is not as simple as closing a newspaper or silencing a radio broadcaster, Omojuwa said. During Nigeria’s Twitter blackout, for example, Nigerians still could access the platform using virtual private networks operating through other countries.

“It’s such a democratized space,” Omojuwa said. “You can’t stop people from talking.”

Legal Limitations

The 39 African nations that have passed cybercrime legislation say they’re targeting misinformation and national security risks. Critics say the laws threaten privacy and put people at risk of arrest for expressing themselves online.

“Governments haven’t really caught up to what freedom of expression in the information age really means,” said Setriakor Nyomi, Ghanaian director of technology for the Kenya-based Moringa School, which provides training for technology jobs.

“The question in the information age is how for governments to cope,” Nyomi said during a conversation with Muthoga via Twitter Spaces.

Human rights should guide the process of creating internet regulations, according to Admire Mare, a professor of communication, journalism and media technology at Namibia University of Science. Mare studied cybercrime legislation in the 16 countries of Southern Africa. His report, “Cybersecurity and Cybercrime Laws in the SADC Region: Implications on Human Rights,” cites South Africa as the only country in the region to craft legislation with citizens’ rights in mind.

“In countries such as Zambia, Zimbabwe, Namibia and Malawi, there is deep-seated fear that existing and new legislation are already being used for surveillance purposes,” Mare wrote in the report published in conjunction with Zimbabwe’s Media Institute of Southern Africa (MISA).

Zimbabwe’s Data Protection Act bill bans messages inciting violence against people or property, bans transmitting false information meant to cause harm, and bans unsolicited emails, commonly referred to as spam.

MISA says the law lacks safeguards to guarantee that it won’t be used to block civil society work, punish whistleblowers and violate the constitutional right to free expression. Before the bill passed, Transparency International Zimbabwe said it would hinder the public’s ability to reveal government corruption.

“The authorities’ loose interpretation and implementation of legislation is already used to repress the citizens they are supposed to protect,” Muchaneta Mundopa, executive director of Transparency International Zimbabwe, wrote in the group’s analysis of the then-bill. “This bill will make matters worse.”

Mundopa cited the case of journalist Hopewell Chin’ono, who was charged under previously existing laws with inciting violence after exposing corruption in the government’s procurement process for COVID-19 medical supplies. Whistleblowers such as Chin’ono need social media to alert the public to suspicious cases, Mundopa said.

“We therefore view the proposed legislation as the government’s latest attempt to silence civil society and media and prevent us from playing our oversight role,” Mundopa wrote.

Nigeria targeted social media with two proposals that met with stiff resistance from free speech activists. In 2015, the so-called Frivolous Petitions bill targeted misinformation online and criticism of public officials with fines of up to $10,000.

Free speech activists argued that the bill helped public officials silence critics and launched the #NoToSocialMediaBill campaign on Twitter. Facing public opposition, legislators eventually killed the bill.

Another social media bill drafted in 2019 was designed to criminalize the publication of false or malicious information online. That bill, too, eventually was withdrawn.

Omojuwa said Nigeria’s two attempts at restricting communication online have put citizens on alert. “Anything the government does in the future, there will always be pushback,” he said.

Media and Self-Censorship

Alongside internet shutdowns and legislative efforts to regulate online speech, Africa’s free expression advocates also confront growing Chinese and Russian influence in the continent’s media environment.

China has spent many years building a continental network of print and broadcast media to promote its own pro-government brand of journalism. China also spends heavily on advertising among some for-profit news outlets and provides others with expensive equipment such as satellite dishes as a way of gaining sway.

China sponsors hundreds of African journalists each year to receive training in Chinese newsrooms. There, they learn China’s brand of journalism that emphasizes support for government policies rather than traditional reporting designed to hold government accountable to its citizens.

“In the spirit of the Beijing regime, journalists are not intended to be a counter-power but rather to serve the propaganda of states,” Christophe Deloire, secretary-general of Reporters Without Borders, wrote in its report, “China’s Pursuit of a New World Media Order.”

Russia takes an even more heavy-handed approach. Through its Wagner Group private military contractor, it has launched a Russian-backed radio station in the Central African Republic (CAR) that broadcasts music along with news and talk shows.

CAR President Faustin-Archange Touadéra’s Russian national security advisor, Valery Zakharov, installed two Russian public relations experts in his office to boost the president’s image.

Meanwhile, much of the CAR’s news media has taken a pro-Russian stance, giving extensive coverage to Russian actions such as donating sports equipment to a school. With no advertising to support their work, reporters in the CAR sometimes take money to write pieces favorable to the Russians, according to analyst Thierry Vircoulon, coordinator for the Observator for Central and Southern Africa at the French Institute of International Relations.

China’s media strategy belongs to its “borrowed boat” philosophy, which uses African news outlets and reporters to publish stories favorable to China.

The smaller the media market, the greater China’s influence, according to Dani Madrid-Morales, a professor at the University of Houston and expert in China’s media machinations in Africa.

“What China has been able to do is establish these relationships at the personal level,” Madrid-Morales told ADF. “By creating these links at the personal level, China helps gate-keep what information goes out.”

That, he said, creates a form of censorship more subtle than internet shutdowns or legislative control: self-censorship by media outlets that soften coverage to avoid losing financial support and favorable reporting by journalists trained to avoid challenging those in power.

South Africa’s IOL media network recently was sold to a group with Chinese investors. Soon after, the network’s Western-trained editors were replaced with editors more favorable to the Chinese model. When columnist Azad Essa criticized China’s treatment of its Uyghur minority, he lost his position the next day.

“I had, it would appear, veered into a nonnegotiable arena that struck at the very heart of China’s propaganda efforts in Africa,” Essa later wrote in Foreign Policy.

Looking Ahead

What does the future hold for freedom of expression within Africa’s media and online communities? Overall, the trend is toward more restrictions, according to Kian Vesteinsson, an analyst at Freedom House.

“Unfortunately, internet freedom has declined across Africa in recent years,” Vesteinsson wrote. “At a high level, challenges to democratic transitions in countries like Ethiopia and Sudan have sharpened the decline of internet freedom in those countries.”

Omojuwa said Nigeria’s Twitter blackout proved an embarrassing failure but could inspire imitators elsewhere as more Africans find their voices on the internet.

“I think a lot of governments on the continent are looking at how Nigeria pushed Twitter around,” he said. “Nigeria got away with it.”

The impact of restrictions on free expression will be detrimental to democracy, he said.

“If the people don’t have the ability to speak, what’s the point of democracy?” Omojuwa said.