Things did not go as planned.

On May 15, 2020, 10 pirates boarded the Chinese-flagged Hailufeng 11, subdued the 18 crew members and turned off its automatic identification system (AIS). The AIS transponder broadcasts the boat’s location, and the pirates believed switching it off made the vessel invisible to monitoring systems.

But authorities were still watching.

Having received an urgent call from the vessel’s owner, authorities were able to manually plot the last known location of the Hailufeng. They monitored its movements in real time using maritime domain awareness (MDA) tools shared by all countries in the region. As the hijacked vessel crossed through Ghanaian, Togolese and Beninese waters, MDA professionals from those countries tracked it, exchanged information and dispatched boats to chase it.

When the boat crossed into Nigerian waters on May 16, the Nigerian Navy Ship Nguru was waiting. The Nguru pulled up alongside the fishing boat about 140 nautical miles south of Lagos and ordered it to cut off its engines. When the pirates refused, Nigerian commandos conducted an opposed boarding, climbing aboard the Hailufeng while it sailed at more than 9 knots.

There were no injuries to Sailors or crew, and the Nigerian Navy escorted the Hailufeng back to Lagos Harbor and handed the pirates over for prosecution.

“The Nigerian Navy has the capability and willpower to deal with such perpetrators,” said Commodore Ibrahim Shettima of the Nigerian Navy when announcing the arrests.

Shettima added a special thanks to neighboring Benin, which shared information with Nigerian authorities. “This underscores the need for increased regional cooperation in terms of information sharing and further deepening of response capability,” Shettima said.

The thwarted hijacking highlights how far the region has come in a few short years. The cooperation, technology and training on display during the 39-hour rescue effort would have been impossible until recently, experts say.

It “demonstrated the mastering of the use of vessel monitoring systems by experts in the region and its usefulness for the monitoring of vessels, the fight against [illegal] fishing and the protection of human lives and goods,” said Seraphin Dedi, secretary-general of the Fisheries Committee for the West Central Gulf of Guinea.

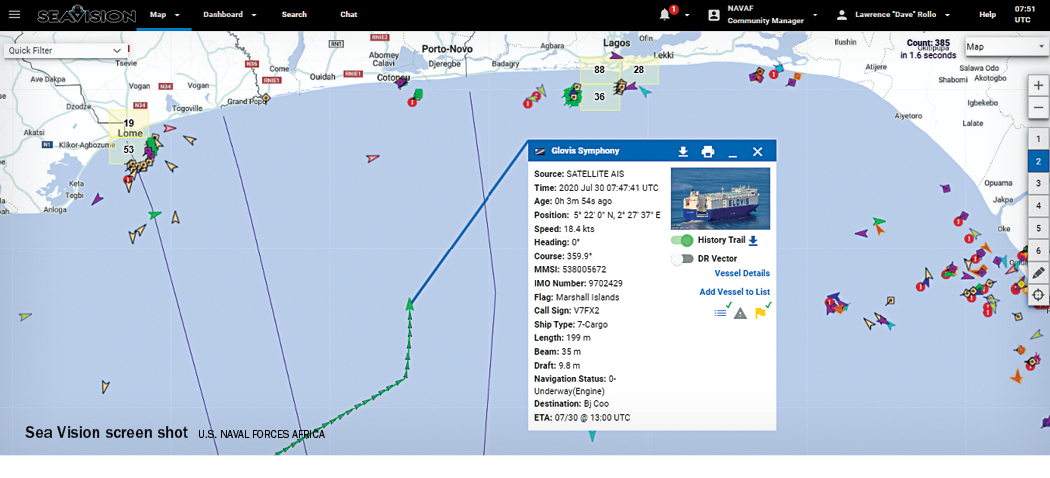

Sea Vision

Tracking all the ships crisscrossing a vast expanse of sea is difficult. In West Africa where navies may only have a handful of deep-water vessels and few aerial assets, it’s even tougher. Technology can be a force multiplier.

Since 2012, a low-cost digital tool has played a major role in improving MDA for coastal African countries. Sea Vision was created by the U.S. Department of Transportation at the request of Naval Forces Africa (NAVAF) and was offered free to African navies. At the time, maritime crime was a growing threat, and navies around the world raced to catch up. “We had always been good about tracking enemy forces — red forces — and our forces –– blue forces. But tracking merchant ships, we had never really done it that much,” said NAVAF MDA project manager David Rollo.

Sea Vision is an unclassified MDA tool requiring only an internet connection, username and password. It lets users track commercial vessels globally. Using AIS data gathered from coastal radar, satellite and other sources, Sea Vision gives a complete picture of where a ship is, where it has been, and who and what is on board. This was a game changer for many West African countries, and it was adopted up and down West Africa from Angola to Mauritania.

“It quickly expanded,” Rollo said. “There were a lot of people using it because at that time there were a lot of countries that didn’t have their own coastal radars.”

Today, Sea Vision is the only MDA tool shared by the 25 West and Central African countries that are part of the regional maritime security architecture known as the Yaoundé Code of Conduct. Users, typically in the maritime operations centers of individual countries, can create vessel lists, tailored searches and alerts based on a wide range of criteria. There also is a chat function that lets users exchange information. There are community groups in which users can ask questions or display information for all to see.

This MDA capability and the information exchange have led to quicker responses and better awareness of what is happening, particularly in the Gulf of Guinea.

“It used to be if a fishing trawler got kidnapped, it went up to the chief of naval staff of one country, he’d contact the CNS of another country and it might trickle down to lower levels, but it’d be two, three days and by then it’s too late,” Rollo said. “Now these guys are passing information quickly. It’s amazing.”

The collaboration is bolstered by the annual U.S.-sponsored maritime exercise Obangame Express. For the past decade Obangame has allowed MDA professionals from West African countries to gather yearly, collaborate and build trust.

The collaboration is bolstered by the annual U.S.-sponsored maritime exercise Obangame Express. For the past decade Obangame has allowed MDA professionals from West African countries to gather yearly, collaborate and build trust.

“All these guys work together during exercises. And organizers purposely take people from different countries and put them together,” Rollo said. “Now they all know each other, and they chat on a professional and personal level. So, when something happens, they already have guys they can get in touch with.”

Yaoundé Code of Conduct

The rescue of the Hailufeng also highlights the development of the Yaoundé Code of Conduct. Signed in 2013 by 25 countries in West and Central Africa, it provides the structure for joint maritime operations, intelligence sharing and harmonized legal frameworks. The code includes five zones, two regional centers and the Interregional Coordination Centre that watch over 6,000 kilometers of coastline and 12 major ports.

According to an analysis by Dr. Ian Ralby, an expert on maritime security and CEO of I.R. Consilium, the information about the May 15 hijacking was shared rapidly and accurately to appropriate authorities. He wrote that the Ivoirian Fisheries Ministry first sounded the alert and then shared information with the Permanent Inter-Ministerial Commission for State Action at Sea, which shared it with the zonal and regional authorities within the Yaoundé architecture.

Ralby said information sharing was led by the Multinational Maritime Coordination Centre of Zone E, which includes Benin, Nigeria and Togo. The regional center known as CRESMAO, which handles the West African waters, played a coordinating role as did its Central African counterpart, CRESMAC, which was prepared to dispatch boats if the chase extended beyond Nigerian waters.

“While the Nigerian Navy deserves credit for the operational success, there are a lot of institutions without whom the situation would not have been resolved so quickly and successfully,” Ralby wrote in an article published by The Maritime Executive.

The successful interdiction stood in contrast to the 2016 hijacking of an oil tanker, the MT Maximus. During that incident, regional navies relied heavily on foreign navies for help.

“Many have argued that the 2016 incident would not have been a success story without the assistance of the foreign navies, working to track the vessel and coordinate the flow of information about it,” Ralby wrote. “This time, the Yaoundé Architecture and the states of the region were able to do so without any foreign involvement.”

The 10 arrests highlighted another positive development. In 2019, Nigeria enacted the Suppression of Piracy and Other Maritime Offences Act. This modernized the country’s anti-piracy laws and outlines tough punishments of 15 years to life in prison and fines of up to 500 million naira, or $1.3 million, for people or organizations convicted of maritime crimes.

During recent iterations of Obangame Express, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime has analyzed national maritime laws and held mock trials for piracy. Several countries, including Nigeria, have updated or are in the process of updating their anti-piracy laws.

The pirates who hijacked the Hailufeng will be among the first tried under the new statute in Nigeria.

“Our recent arrests have shown the international community that we are not handling illegalities in our waters with kid gloves,” said Dr. Bashir Jamoh, director-general of the Nigerian Maritime Administration and Safety Agency.