ADF STAFF

Arab Spring protests swept across North Africa and the Middle East in the early 2010s as citizens rose up in the face of years of autocratic rule. The protests produced a range of results, from the lasting chaos in Libya to a flirtation with democratic rule in neighboring Egypt.

The Arab Spring’s reach extended into Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates and Yemen. It lit the fuse that exploded into the bloody Syrian civil war, which persists to this day.

But in Tunisia, a nation of 12 million people nestled between Algeria and Libya, things were different. Those differences can be attributed in large part to characteristics of Tunisia’s military and how it responded to the protests. The decisions commanders made at a crucial moment helped steer the nation away from autocratic rule toward what has been a fairly stable — if imperfect — democracy ever since.

Tunisia’s example can provide a valuable road map for other militaries. When a nation stands at the brink of democracy, how its military responds — or chooses not to respond — can make a crucial difference.

“What makes the difference between a democratic handover and a stillborn transition? Where the military’s loyalty lies,” wrote Dr. Nathaniel Allen of the Africa Center for Strategic Studies and political scientist Dr. Alexander Noyes at the Rand Corp. in 2019. “When security forces backed a dictator’s political party over the opposition, as in Togo and Zimbabwe, the old regime has remained in power through a coup or fraudulent election. But when security forces ousted incumbents, as in Sudan and Algeria, or stayed on the sidelines, as in Ethiopia and Angola, there have been opportunities to transform the political system through genuinely free, peaceful and fair elections.”

TUNISIA’S EXPERIENCE

Tunisia’s military ultimately made the best choices for the citizenry and for the prospects of democracy in 2011. But perhaps most fascinating are the motivations for why it made those choices.

The military’s size, structure and connection to the regime of then-President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali offers perspective. As protests began in December 2010, Tunisia’s small Armed Forces — about 40,000 uniformed personnel — essentially was disconnected from the Ben Ali regime because the autocratic president had created a system in which the national police force and the presidential and national guards held most of the power.

That estrangement worked against the regime when Soldiers refused to stand between protesters and Ben Ali, who gave up power and fled the country in January 2011. More than 10 years later, Dr. Sharan Grewal calls Tunisia the Arab Spring’s “lone success story” for managing to maintain its democracy, however tenuous it may seem.

Ben Ali and his predecessor, Habib Bourguiba, had relied on a fragmented security system that distanced the military from the regime in favor of the other security forces, Grewal, of the College of William & Mary in the United States, wrote for the Brookings Institution in January 2021.

Ben Ali and his predecessor, Habib Bourguiba, had relied on a fragmented security system that distanced the military from the regime in favor of the other security forces, Grewal, of the College of William & Mary in the United States, wrote for the Brookings Institution in January 2021.

“This counterbalancing was a major advantage during the revolution and transition, as the marginalized military stepped aside from Ben Ali and subsequently allowed the transition to proceed without any vested interests,” Grewal wrote. “Moreover, counterbalancing meant that without the military, the internal security forces could not on their own preserve Ben Ali nor stage a coup and thwart the transition in 2013.”

In short, the military helped empower the revolution and the nation’s march toward democracy by rejecting its own long-standing marginalization. Ben Ali and his predecessor, as Grewal wrote for the Carnegie Endowment in February 2016, kept Soldiers in the barracks, underfunded, underequipped, and away from the levers of political and economic power.

“This lack of vested interests allowed it to quickly move beyond Ben Ali following his ouster in January 2011 and then stand much more removed from domestic political developments than other militaries in the region,” Grewal wrote for Carnegie.

When Bourguiba was in power, he eventually came to rely more on military personnel for security, and some of them assumed more of a political role. But Ben Ali, formerly a brigadier general, began to rise through civilian political positions and eventually removed Bourguiba in a 1987 soft coup.

“Bourguiba did not like the army, but he respected it,” retired Gen. Said el-Kateb, a former chief of staff of the Armed Forces, told Grewal. “The military under Bourguiba were treated better than the police, as far as budget, equipment, and training. Under Ben Ali, the budget allocated to the police was higher than the military’s; the number of police officers increased dramatically. We could feel our marginalization.”

THE POWER OF MILITARIES

Tunisian military commanders could have ordered Soldiers into the streets to violently crush the civil rebellion from the beginning. Instead, troops sided with the people and, ultimately, democracy. Now Tunisia has what Grewal calls “one of the world’s most progressive constitutions” and is continuing its long, complicated journey toward a more established democracy.

Unfortunately, not all African militaries have made the same calculus as Tunisia’s did. Recent history is replete with examples of militaries making the wrong decisions when it comes to intervening in political affairs. The continent’s record on coups provides evidence.

Unfortunately, not all African militaries have made the same calculus as Tunisia’s did. Recent history is replete with examples of militaries making the wrong decisions when it comes to intervening in political affairs. The continent’s record on coups provides evidence.

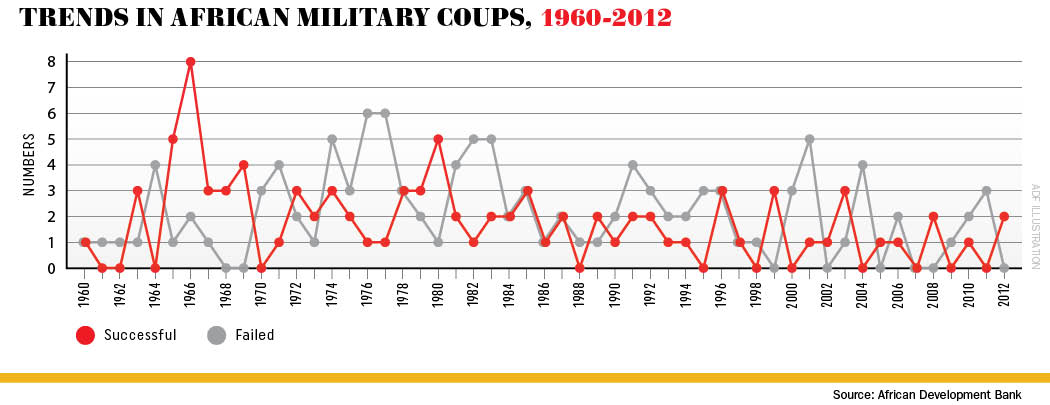

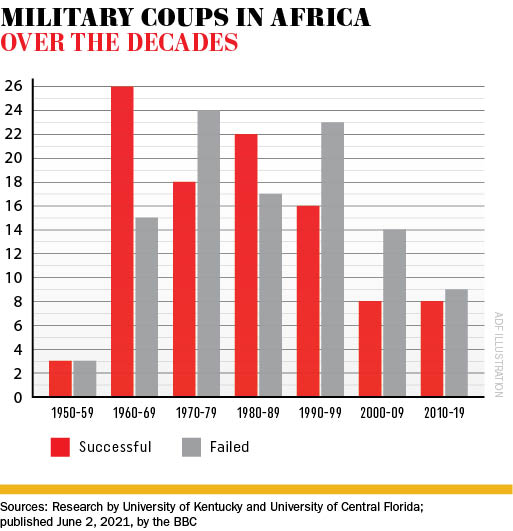

According to the African Development Bank (AfDB), there were more than 200 military coups between the beginning of the African independence movement in 1960 and 2012. About 45% were successful, resulting in a change of power at the top. The study looked at 51 African countries, and only 10 of those never had a successful, attempted or plotted military coup in that time span: Botswana, Cabo Verde, Egypt, Eritrea, Malawi, Mauritius, Morocco, Namibia, South Africa and Tunisia. Since that time, Egypt has had a military coup.

The AfDB study found that in the same time frame, 80% of the sampled nations had at least one coup or failed coup. Nearly two-thirds — 61% — had between two and 10 military coup attempts.

When militaries intrude in the politics of a democratic state, they trample on popular sovereignty, Craig Bailie, lecturer in political science at South Africa’s Stellenbosch University, wrote for the African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD).

African militaries “must know, understand and accept” their place with regard to politics. “This will lead to what civil-military relations scholars refer to as ‘democratic control’ of the military,” Bailie wrote. “Without the military’s acceptance of the principles of democratic control, democracy cannot exist.”

Dr. Naison Ngoma, vice chancellor of the Copperbelt University in Zambia, summarized the generally accepted principles and responsibilities of professional militaries in “Civil-military relations in Africa: Navigating uncharted waters” for the Institute for Security Studies’ African Security Review. Militaries must:

- Be accountable to civil authorities, society and appropriate oversight agencies.

- Adhere to domestic and international rule of law.

- Conduct planning and budgeting transparently.

- Respect human rights and uphold cultural civility.

- Subject themselves to political control of operational and financial matters.

- Consult regularly with civil society.

- Conduct themselves professionally.

- Support collaborative peace and security.

“Although these principles are not always easy to adhere to, CMR [civil-military relations] in Africa have moved towards and will continue to move closer to observing these principles,” Ngoma wrote. “Therefore it is essential for African militaries to include civic education programmes at all levels of education and training in order to gain a better understanding of and commitment to these principles.”

WHAT FUELS MILITARY LOYALTIES?

Allen and Noyes point to five things that can indicate how militaries will behave amid a potential transition to democracy — whether they will support it or work against it.

First, the more inclusive, bigger and peaceful that popular protests are, the less likely Soldiers are to react violently to them. If protesters are united across economic, ethnic and religious lines, armies will be less likely to suppress them, especially if rank-and-file Soldiers are representative of the society. Such was the case in Algeria, Ethiopia and Sudan.

Second, if military forces are broadly representative and recruited and promoted on merit, they are more apt to support democratic transitions.

One crucial point that Allen and Noyes make is that militaries often will act in their own best interests. Budgets, pay, equipment, living conditions and more can be influential. The Tunisian Army’s marginalization in favor of other security forces is an example. Soldiers there did not see fit to intervene against the public. Likewise, the Ben Ali regime did not depend on them or deploy them in its defense.

This sense of self-interest can cut the other way. In Zimbabwe, for example, the military is closely aligned with political officials. Although it deposed dictator Robert Mugabe in 2017 after 37 years in power, the military installed another civilian with whom they had close ties.

“This retained their access to revenue, while avoiding the political baggage that would have accompanied their hanging onto power indefinitely,” Bailie wrote for ACCORD.

The military’s choice to replace Mugabe, Emmerson Mnangagwa, narrowly avoided a runoff in a disputed 2018 election.

Political leaders also can build on personal connections to military forces by using concessions and incentives to help turn recalcitrant military officials toward support of more democratic reforms. Such recently has been the case in Ethiopia, where Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has instituted a number of changes, including lifting martial law, releasing political prisoners and softening relations with neighboring Eritrea. Ahmed is a former Army colonel. Likewise, civilian opposition must be able to communicate effectively with security forces.

“Opposition groups in Sudan helped end [President Omar al-]Bashir’s rule in part by appealing directly to security forces by avoiding violence, staying united and holding sit-ins in front of military headquarters,” Allen and Noyes wrote.

Finally, outside training and capacity building are most effective when prioritizing accountability, financial integrity, and human rights over training and equipment provisions.

The path from tyranny to democracy isn’t easy. Tunisia still struggles to fully consolidate its hard-won democratic reforms. Sudan stands on a precarious precipice more than two years after removing a dictator; it still could easily fall into chaos. African militaries built on professionalism, appropriate training and protecting the public, not serving a regime, are best positioned to support any successful transition toward democracy.