ADF STAFF

When war broke out in Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region in 2020, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed quickly ordered the severing of the region’s internet and telephone connections.

Abiy’s order cast Tigray into an information blackout, making it nearly impossible for the rest of the country and the world to know what was going on there as fighting and human rights violations escalated.

Abiy’s order ran counter to democratic progress in the country. It also served as a catalyst for more protests and fighting.

“It’s like they turned the clock back 30 years,” Eyassu Gebreanenia, a resident of the Tigrayan city of Mekelle, told Reuters. “People are suffering — but you might not know about it because we’re cut off from the world. It’s pretty depressing.”

Since Abiy took power in 2018, Ethiopia has experienced multiple internet shutdowns, including eight in 2019 alone. These shutdowns often are justified by citing national security or counterterrorism needs — reasons that human rights groups dispute.

Abiy is not alone in using internet shutdowns against his citizens. Since Guinea became the first African country to impose an internet blackout in 2007, full or partial shutdowns, or the deliberate slowing of access known as throttling, have become common. In many cases, leaders use the tactics to exert control, particularly in the face of protests, civil unrest or to suppress political opponents.

According to internet-freedom advocate SurfShark, 80% of people on the continent have felt the impact of internet or social media shutdowns in recent years. Of 90 disruptions SurfShark has recorded across Africa, 66 were related to protests or what the group labels political turmoil.

Internet advocates have coined a term for these online tactics: digital repression.

UNPREDICTABLE EFFECTS

Internet blackouts mirror the decades-old technique of stifling dissent by shutting down broadcast stations and closing print outlets. But modern shutdowns have an even bigger impact than those of years past.

“Network shutdowns trigger a series of cascading, often unpredictable effects on human rights and economic development,” write researchers Moses Karanja and Nicholas Opiyo. They are coauthors with Jan Rydzak of an article on internet shutdowns and protests recently published in the International Journal of Communications.

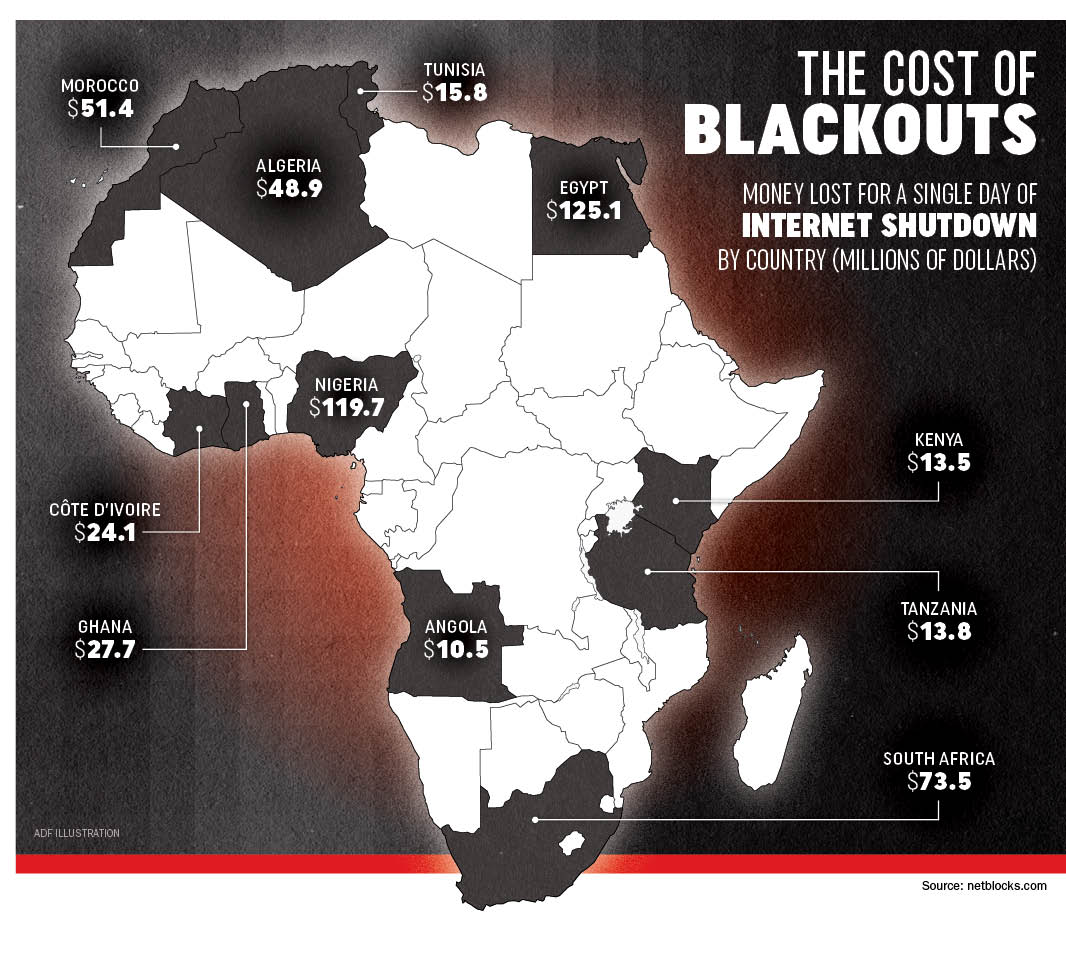

By interrupting online commerce, internet shutdowns can cause billions of dollars in damage to national economies. Online analyst NetBlocks estimated that Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari’s block of Twitter in 2021 cost the country $1.6 billion in economic losses and obstructed access to vital health information related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Lost business and disruptions to daily life can have the secondary effect of expanding protest movements instead of shutting them down.

During one of Burkina Faso’s three internet blackouts in 2021, university student Ali Dayorgo told Voice of America that the shutdowns blocked him from working and made him sympathetic to the protests happening against the then-government.

“I feel the anger of the youth,” Dayorgo said.

In a blow against one form of digital repression, Zimbabwe’s High Court reversed that government’s internet shutdown in early 2019 that was intended to quash protests over rising fuel prices.

The court ruled that the government had no authority to institute the blackout, which opponents argued was imposed to censor news about the government’s heavy-handed response to protests.

As leaders grasp the negative effects of wholesale internet shutdowns, they have taken more subtle measures to exert control and suppress dissent.

Increasingly, anti-terrorism laws have become authoritarian leaders’ method of choice to monitor their citizens’ internet use, track their movements and in some cases act against their political opposition — actions internet advocates decry as a violation of privacy and human rights.

“Several African governments have embraced digital authoritarianism characterized by aggressive and sophisticated measures that curtail internet freedoms,” researcher Paul Kimumwe wrote in a report by the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA).

Africa’s rapid adoption of digital technology has proved to be a double-edged sword, according to Kimumwe. Even as digitization expands people’s ability to learn, earn and organize, it also has given governments more tools to surveil their citizens, often through automation and around the clock.

“Although state surveillance is not new, it has dramatically expanded with increased digitization,” Kimumwe wrote in the CIPESA report.

Lesotho, Mozambique, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia have passed laws intended to confront online crime and terrorism that also make it easier for the government to track and repress legitimate activity, according to Kimumwe.

Lesotho, for example, requires internet service providers to funnel internet traffic through the country’s Lesotho Communication Authority, where it can be monitored in real time, an action that perpetuates the government’s infringement on citizens’ privacy, Kimumwe writes.

In Uganda and Zambia, company officials who fail to comply with communications laws face large fines and jail time. Such high penalties can force service providers to comply even if they believe the requests are legally dubious, according to Kimumwe.

With the rapid spread of mobile technology, governments are becoming savvier in the ways they approach internet shutdowns.

Rather than impose blanket blockades, governments now can target their censorship efforts to certain types of technology. They can throttle the flow of information to and from the smartphones held by protesters while leaving the desktops in business offices untouched.

“Throttling can be attributed to the desire to avoid social outrage and political backlash for disrupting connectivity while limiting what can be achieved on the platforms,” Karanja, Opiyo and Rydzak wrote.

A SIGN OF WEAKNESS

Analysts say the shifting nature of digital repression fails to hide a simple fact: Shutdowns and politically motivated censorship are a sign of a government’s weakness.

Simply put, weak governments repress online activity they don’t like, according to author Stephen Feldstein, who addressed digital censorship around the world in his 2021 book, “The Rise of Digital Repression.”

One important predictor of digital repression is the style of government, according to Feldstein.

“The more authoritarian a regime is, the more likely it is to rely on these techniques,” Feldstein said during a discussion of digital repression by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Paradoxically, governments that tighten their grip on their citizens’ electronic lives undermine their own authority by pushing people to find ways around the shutdown.

That was the case with Nigeria’s Twitter blackout. Thousands of Twitter users got around the blackout by using virtual private networks, or VPNs, to access the internet through other channels.

Extensive social media blackouts in Cameroon (93 days) and Chad (16 months) failed to stop citizens from getting around the blackouts to reveal them to the world and demand change.

Internet blackouts can push people to strengthen their offline networks to obtain information and, in the case of protests, develop resistance. By denying people an online space to vent their opinions, authoritarian governments might actually force those energies into the street where they can turn violent.

Ethiopia’s social media blackout targeting the Amhara and Oromia regions in 2017 “completely failed to hinder the patterns of protest that led up to it,” the researchers note. Instead, by pushing protestors offline, the shutdowns came with a surge in ethnic clashes.

Instead of taking an adversarial approach to citizens’ internet use, communication experts say, African governments could collaborate on laws that protect free speech and access to information while blocking terrorist groups and threats to stability.

The short-term gain of throttling or shutting down the internet is outweighed by the economic harm and social upheaval those actions cause, they say.

“Shutting down communications networks is not a guarantee of success in quelling protests,” Karanja, Opiyo and Rydzak wrote.