ADF STAFF

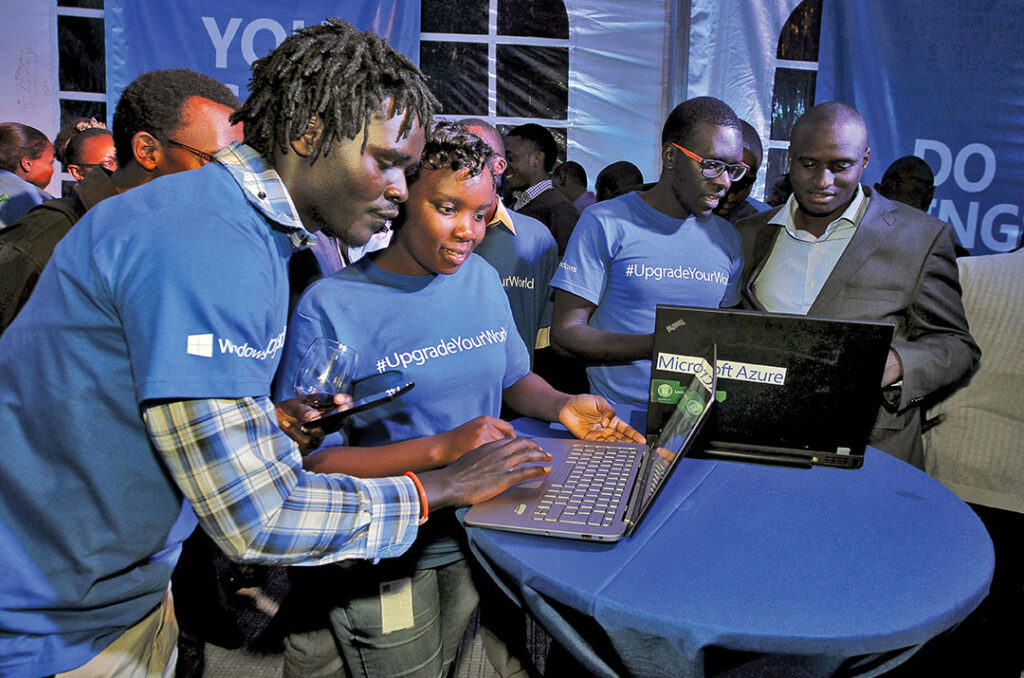

With great fanfare, Kenya launched its upgraded e-Citizen digital platform in 2023. The system offers access to 5,000 government services from more than 100 ministries and agencies, marking a leap forward in the ability of citizens to get digital access to their government.

“Not many countries can achieve what we have achieved,” Kenyan President William Ruto said. “Whenever I talk to other leaders, they wonder how Kenya can digitize this number of government services. It was possible because we have creative, innovative, hard-working young people in the republic.”

Just three weeks later, a hacker collective calling itself Anonymous Sudan claimed responsibility for a barrage of distributed denial-of-service attacks that halted traffic on e-Citizen.

As one of the continent’s most advanced digital economies, Kenya has become a model of modernization. But with its growth have come risks. The East African country has been hit with a surge in cyberattacks — 860 million incidents in the past year, Kenya’s Communications Authority said on October 3, 2023.

Cyberattacks by state and nonstate actors are increasing across Africa, and experts are calling on governments to provide more funding and resources for cybersecurity.

“Cybersecurity is not adequately prioritized by both governments and civil servants alike,” Anna Collard, senior vice president of content strategy for security software company KnowBe4 Africa, told ADF. “Only 18 out of 54 countries in Africa have completed national cybersecurity strategies, and only 22 African countries have national computer incident response teams (CIRT).

“Many countries and sectors are completely reliant on private-sector investments.”

Dr. James Shires is another among a chorus of voices warning African countries about the risks that come with digital growth, but he also cautions against generalizing cybersecurity on the continent.

“There’s a real difference in sectors,” the senior research fellow in the Chatham House International Security Program told ADF. “Kenya and Nigeria have really good sectors in terms of building CIRTs.

“Tunisia and Egypt have really been leaders in several areas of cybersecurity. There’s a strong financial sector in South Africa that I’m using as a case study, and the cybersecurity is really impressive and very mature.”

But, along with the rest of the world, African countries face a variety of threats online.

Hacktivists and Russia

The hacker collective Anonymous Sudan surfaced in January 2023 as a Russian-speaking channel on Telegram, an instant messaging app. Experts say the group has no verifiable links to Sudan and has collaborated with two notorious Russian cybergangs.

In March 2023, after researchers noted that the group conversed mostly in Russian, Anonymous Sudan deleted its older posts and started posting in rudimentary Arabic. It later adopted the Sudanese dialect.

“Anonymous is a very slippery label. It can be co-opted,” Shires explained. “While it did have a strong hacktivist identity earlier on, Russia especially has used a variety of hacktivist labels to further its own ends. There are other Russian operations that pretended to be ISIS, for example, in France. So, there’s a real range of what the cybersecurity industry called false flags in Russian cyber operations. And they’re very good at them.”

Many in the cybersecurity community have assessed Anonymous Sudan’s attacks, origins and modus operandi and see clear ties to Russia. Some suspect that the funding necessary for the group’s attacks, including the attack on Kenya’s e-Citizen, indicate Russian involvement.

When conducted by countries, cyber operations such as espionage and hacks serve strategic objectives. The hardware is expensive, and the skills required are in high demand, Shires said.

“They’re a scarce resource,” he said. “They are expensive, not in military terms, but still not cheap. It’s a clue, not a conclusion. Some nonstate actors can be very capable, but generally, sophistication is an indication of resource, and resource is an indication of state backing.”

Russia also is conducting information warfare in parts of Africa. Through its complex network of shell companies, mercenary groups and other proxies, Russia has been unrelenting in conducting misinformation and disinformation campaigns on African social media and online platforms.

Cultivating, paying and using local influencers, Russian propaganda and fake news have grown in sophistication. In some African countries, Russian proxies own and operate media entities.

These cyber awareness risks fall into a category that Shires refers to as threats to integrity.

“Do people trust what’s online? Do they trust what they see from governments or on social media platforms?” he said. “There’s a lot of disinformation and misinformation, and that makes the information ecosystem less reliable and less trusted.”

China’s History of Cyberattacks

On May 24, 2023, a Reuters investigation revealed that Chinese hackers had engaged in a widespread, yearslong campaign of cyberattacks on the Kenyan government regarding the debt it owed to China, among many other economic and political issues.

It started in late 2019 when a Kenyan government employee unwittingly downloaded a document infected with malware that allowed hackers to infiltrate a server used exclusively by Kenya’s primary spy agency, the National Intelligence Service, and gain access to other agencies.

“A lot of documents from the ministry of foreign affairs were stolen, and from the finance department as well,” a Kenyan cybersecurity expert told the news service.

Two sources in Reuters’ investigation said the hacks show that China uses espionage and illegal cyber breaches to surveil governments and protect its economic and strategic interests.

For Collard, Shires and many other experts, the news brought to mind another infamous, yearslong Chinese hack.

In 2017, officials found bugs at the headquarters of the African Union in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, which was built in 2012 as a $200 million gift from the Chinese. Investigations revealed that classified data had been copied to servers in Shanghai for five years.

Nairobi-based investment analyst Aly-Khan Satchu said the AU hack was “really alarming,” because it showed that “African countries have no leverage over China.”

“There’s this theory in Africa that China is Santa Claus. It isn’t,” he told the Financial Times newspaper. “Our leaders need to be disavowed of that notion.”

The AU hack and the May 2023 Kenya hack are revealing, Shires said, but not surprising.

“You see China’s strategic interest in gathering data from different places on the African continent,” he said, “and you would expect them to be persistent, to be patient in a strategic target.”

China denied any involvement in the AU hack, just as it did in its May 2023 response to the Kenya allegations. But in the digital environment it is harder than ever for attackers to cover their tracks.

Chinese digital technology is nearly ubiquitous in Africa, from government surveillance systems to smartphones, a market dominated by Chinese brands.

“China has been investing heavily in Africa,” Collard said. “Tech companies like Huawei are very prevalent in African organizations and telecoms.”

Huawei, the world’s top maker of cellphone network equipment, sold 70% of the 4G base stations in use on the continent. Because it is poised to dominate the 5G market as well, vast troves of African data are vulnerable to the Chinese Communist Party, which in recent years has enacted expansive laws that require companies to assist in national intelligence gathering.

“Many African governments are inviting China to assist them with their security challenges, including online security,” Collard said. “China is not really seen as a malicious actor, despite evidence of their espionage tactics. Decision-makers here mainly act on price and write off any potential privacy implications due to the cost savings. Others may lack the necessary understanding of what the privacy implications could be.”

Many authoritarian countries in Africa are interested in using Chinese technology precisely for its surveillance, monitoring and suppression capabilities.

“They may see clear benefits in using the censorship mechanisms in Huawei technology and other technology providers,” Collard added.

Countering Cyber Threats

As digital technology proliferates across the continent, Africa is becoming a burgeoning cyber battleground, a shadowy realm of espionage and misinformation.

When it comes to covert intelligence operations, the distinction between the approaches of China and Russia used to be greater.

Five years ago, Shires would describe China’s covert cyber operations as “pretty loud and noisy. They’d go for scale and didn’t mind if they got caught.”

Russia, on the other hand, had more specific targets and went to great lengths to not be identified. Now there’s less of a distinction.

“China has much more sophisticated capabilities,” he said. “They’re targeting critical infrastructure networks, internet infrastructure networks that have impacts in Africa. Just in terms of size, the ability or the scale of Chinese cyber espionage is far greater than that of Russia.

“But rather than having a targeted, stealthy actor [in Russia] and a large, noisy actor [in China], you now have a large, stealthy actor in China as well. So, it’s kind of the worst of both worlds.”

Shires believes that countering these changing strategies requires transparency, persistence and international cooperation. Here is a breakdown of those topics:

Transparency: Sunshine is said to be the best disinfectant. In terms of cyberattacks, public attribution is the naming of a malign actor as the responsible party. “Attention is a good thing, and attention often galvanizes policy responses,” Shires said. “You’re not expecting a reaction from the malicious actor or the particular state that’s being reported on, but you are changing the public perception. That’s a long-term change. But more reliable reports in the public domain make a massive difference to what can be done in the policy space on these issues.”

Persistence: “Over time, the volume of incidents begins to skew both public perception and political perception of [malign actors]. So that’s the indirect result of transparency. But you need transparency plus persistence to achieve that. Because if, for example, in Kenya, China is perceiving that its hacking operations are causing problems with the Kenyan government due to public releases and condemnation of them over time, then that might factor into diplomatic negotiations and then finally into actual cooperation.”

International cooperation: Countries could have more power if they join together to denounce cyberattacks. Shires said countries could make a statement on a regional or continental basis to say: “‘We agree that this is a red line.’ There are well-publicized norms out there that say cyberattacks against critical infrastructure or defensive organizations are out of bounds. And so, if there’s international cooperation within Africa on trying to reinforce those norms, that would be an extremely positive step.”

Collard agrees with the need for a broad coalition of international and regional partners to work with African officials in funding and developing cybersecurity infrastructure, talent, strategies and responses to attacks.

“We need collaboration across private and public sectors and the international community to assist African states with capacity-building and raising awareness among decision- and policymakers, as well as the general public,” she said, because the threats will only continue to grow.

“The majority of cybersecurity incidents go unreported or unresolved, meaning that cyberthreats in Africa are likely much worse than recognized.”