LT. CMDR. DJAIBLOND DOMINIQUE-YOHANN KOUAKOU, CÔTE D’IVOIRE NATIONAL NAVY

Coastal countries in Africa face a variety of maritime threats. These include trafficking; illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing; illegal immigration; and piracy. But countries often lack the resources to monitor and protect their maritime domains.

The task these countries face is enormous. If added together, Africa’s coastal countries are responsible for more than 13 million square kilometers of ocean, far beyond what they can patrol with vessels and traditional aircraft. Sub-Saharan African countries have a total of 420 vessels categorized as “surface combatants,” meaning ships designed for warfare on the open water. This is a significant increase since 2008, when that total was 158, according to a database produced by The Military Balance. But experts say the growth was driven by a handful of countries, and most still struggle to patrol their waters.

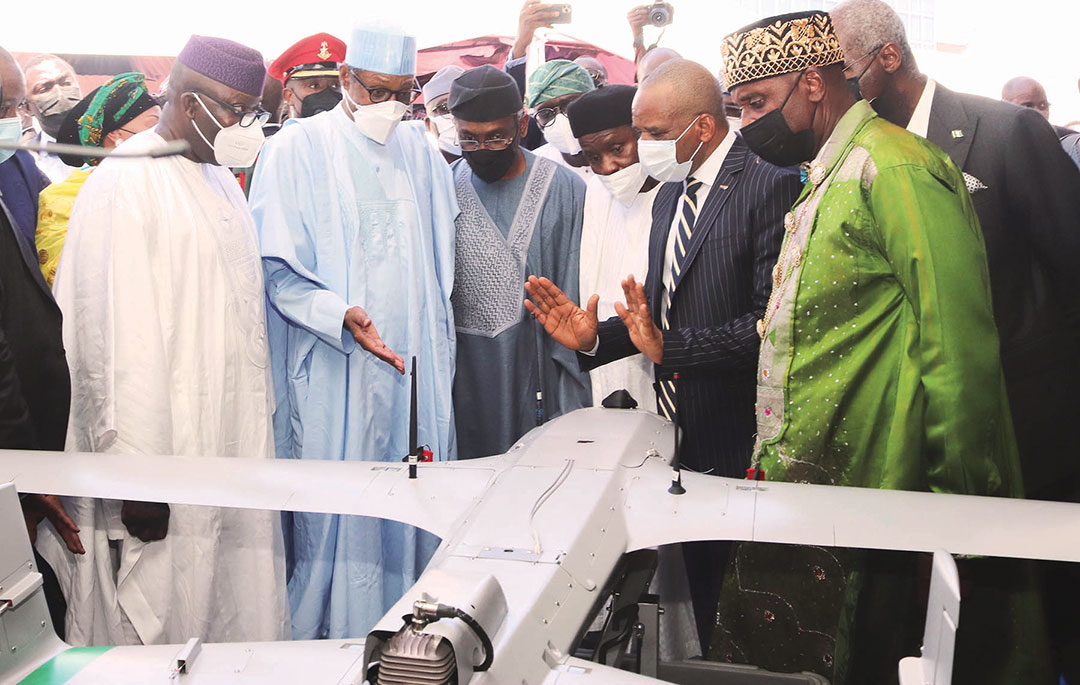

In light of this, nations are looking for cost-effective alternatives to expand their reach. Several Gulf of Guinea states, including Nigeria and Côte d’Ivoire, have turned to drones to improve maritime security, a choice that allows them to bridge a capability gap.

The relative affordability of tactical drone systems can offer savings compared to the high cost of extended sea missions that require ships and large numbers of personnel. Drone platforms equipped with advanced avionics offer operational flexibility thanks to their payloads, which can carry various sensors such as day and night infrared cameras and radars. Their light weight makes them easy to transport and adaptable to many mission conditions. But drones are not a cure-all. They have weaknesses, including a limited range, relatively slow speed and the fact that they fly at low altitudes, which increase their vulnerability to anti-aircraft weaponry. Despite limitations, they are quickly becoming indispensable tools in the field of intelligence collection and surveillance.

A Tool Showing its Value

Militaries have used drones dating to 1937, when the U.S. developed the first radio-controlled unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), known as the Curtiss N2C-2 Fledgling, and used it for target practice. The South African Council for Scientific and Industrial Research developed the first surveillance drones used in Africa. They were flown over what was then Rhodesia in 1978.

Today, drones represent a critical and versatile operational asset for intelligence gathering. Tactical drones address capability gaps such as persistence, autonomy and compatibility with the onboard weapons system, according to a 2010 paper, “Rotary-wing Tactical Drones in Contemporary Engagements,” published by the Foundation for Contemporary Research. Monitoring vessel traffic in an area can be done in record time thanks to the considerable endurance of the drones. Drones also can carry automatic identification systems, which have become one of the main tools for maritime domain awareness. These tools make it possible to identify and classify unrecognized radar echoes, which provides a more complete real-time picture to professionals working in maritime operations centers.

Pirates tend to operate far from shore. A naval force alone cannot cover these areas. The use of a tactical drone with many hours of endurance will widen the areas monitored. For example, the use of aerial drones by the Premier-Maître L’Her of the French Navy was essential in locating the tanker Monjasa Reformer, which was attacked on March 25, 2023. Similarly, drones are integrated into a nation’s system for monitoring maritime and land borders.

Drones represent a force multiplier to support law enforcement at sea and deter crime. Visit, board, search and seizure (VBSS) operations are one of the main missions carried out by warships in connection with the fight against maritime crime. Paired with the use of other naval assets, drones can significantly increase the individual capabilities of vessels during VBSS operations, according to a 2019 paper written by French Navy Rear Adm. Benoit de Guibert. Drones make it possible to have a clear and immediate view of the boarding, to follow the progress of it, and assess risks during these operations.

In the event of contact with pirates or tracking of a pirated ship, the drone allows continuous monitoring. This possibility of remotely monitoring a captured ship is all the more important in hostage-taking, when it is imperative not to provoke an extreme reaction from pirates toward their victims. In addition, the information collected during interventions becomes useful for self-assessment and after action reviews. With the risks inherent in VBSS operations, being able to provide feedback is essential to improve the effectiveness of the team. This efficiency is essential, especially when human life is threatened and urgent actions become necessary.

A growing number of African navies are investing in drone technology. Côte d’Ivoire recently acquired two offshore patrol vessels that will be paired with drones for use at sea. Nigeria relies on drones for its counterpiracy and maritime security project known as Deep Blue. The Seychelles uses two long-range surveillance drones with artificial intelligence to protect its fisheries. The Ghana Navy and the Ghana Boundary Commission use drones to track suspicious vessels and monitor the country’s maritime borders.

UAVs are being used for a variety of maritime tasks such as border patrol, port security, search and rescue, and ship and cargo inspections.

Limits and Constraints on Drone Use

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea defines states’ rights and obligations in maritime spaces. In its Article 19, the convention does not guarantee “innocent passage” for vessels that “launch, land or take on board” a military device in the territorial sea of a state. From a legal point of view, it becomes difficult to classify drones in a category that can benefit from the right of innocent passage, although the provisions are not explicit on this fact. As a result, the use of aerial drones for maritime surveillance is restricted to areas of sovereignty and areas where the law of the high seas applies — that is to say in the territorial sea, the exclusive economic zone and the high seas. Thus, during operations in which transnational criminals are involved, rigor is required to avoid violating the airspaces of other parties, particularly during operations close to borders or zone limits.

The development of computing and communications technologies strongly supports drone development. In a world where these technologies break down barriers, cyber risks have increased. The use of drones at sea often relies on navigation and satellite data. Disruptive practices can jeopardize the platform. One of the most common is “GPS spoofing,” which occurs when a GPS device is diverted from its coordinates, according to a report titled, “Can a new wave of drone tech make Africa’s seas safer?” published by the Institute for Security Studies. This spoofing can cause accidents as serious as ship strikes, which could be interpreted as an act of war. In addition, terrorists can use cyberattacks to take control of equipment by deprogramming then reprogramming it. Finally, data collected by the sensors is sensitive and must be protected to avoid disclosure of classified information. Consequently, naval forces need to enact procedures for assessing and reducing cyber risks related to the use of drones in their operations so they do not compromise missions and equipment security.

The Navy of the Future

The use of drones in the Gulf of Guinea can optimize traditional naval resources and help navies be more flexible and quicker to respond to threats. The advantages linked to their use particularly relate to maritime security operations, such as VBSS and other missions requiring naval forces to have intelligence gathering and surveillance capabilities. But adopting new technology can have disruptive effects on navies. One consequence could be a loss of interest and investment in vessel-based surveillance missions, especially in the Gulf of Guinea where resources are limited. It must, therefore, be remembered that new tools should be adopted to make the overall fighting force stronger, not to replace it or make it obsolete. As de Guibert wrote: “It is important not to submit to new technologies, it’s better to master them to construct the Navy of the future.”

With proper planning and understanding, new technologies such as drones can be an important tool in helping naval professionals carry out their mission of providing safety at sea for commerce, travel, conservation and recreation to thrive.

Lt. Cmdr. Kouakou is an officer in the National Navy of the Republic of Côte d’Ivoire. He has more than 15 years of service and commands a warship. He has an engineering degree in naval operations from the Royal Naval School of Morocco. Additionally, he holds a master’s degree in maritime affairs from the World Maritime University in Malmö, Sweden. He is passionate about securing the seas with a particular emphasis on maritime technology.