ADF STAFF

The Baba Ali, a Seychellois fishing vessel, was passing through the Seychelles exclusive economic zone (EEZ) when authorities intercepted it in May 2021.

Through an operation coordinated by the Seychelles Air Force, Seychelles Coast Guard and its National Information Sharing and Coordination Centre, authorities boarded and inspected the vessel. What they found –– about $1.2 million worth of heroin and hashish –– signifies the magnitude of the regional trafficking threat.

The drug seizure and the arrest of three Seychellois and four Indonesian nationals showed that the island state’s efforts to bolster maritime security were working, Seychellois Fisheries Minister Jean-Francois Ferrari said during a news conference.

“With the help of gathered intelligence, we have been able to carry out an operation on this vessel and have placed them in the hands of the police force,” Ferrari said. “I will not be able to go into details as this is a police case, but according to information we have gathered, the total amount of drugs onboard Baba Ali was three times more than what we picked up, as some have gone missing in the Indian Ocean.”

“With the help of gathered intelligence, we have been able to carry out an operation on this vessel and have placed them in the hands of the police force,” Ferrari said. “I will not be able to go into details as this is a police case, but according to information we have gathered, the total amount of drugs onboard Baba Ali was three times more than what we picked up, as some have gone missing in the Indian Ocean.”

An archipelago about 1,800 kilometers northeast of Madagascar, Seychelles comprises 115 tiny islands, making its waters difficult to police. The same is true for other island states in the Western Indian Ocean, including Comoros, Madagascar, Mauritius, and the French island of Réunion.

For the past 25 years or so, however, the island nations gradually have bolstered maritime security through membership in the Indian Ocean Commission (IOC), which has helped them increase law enforcement cooperation, intelligence sharing and coordination across borders to counter sea crime.

The commission is the only intergovernmental organization composed exclusively of island states. The European Union (EU) funds its maritime security efforts around Africa.

Major Drug Route

The island nations are along a notorious stretch of the Western Indian Ocean that for decades has been a drug transit route. Other maritime issues in the region include illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing; piracy and kidnappings; and trafficking in weapons, people and wildlife.

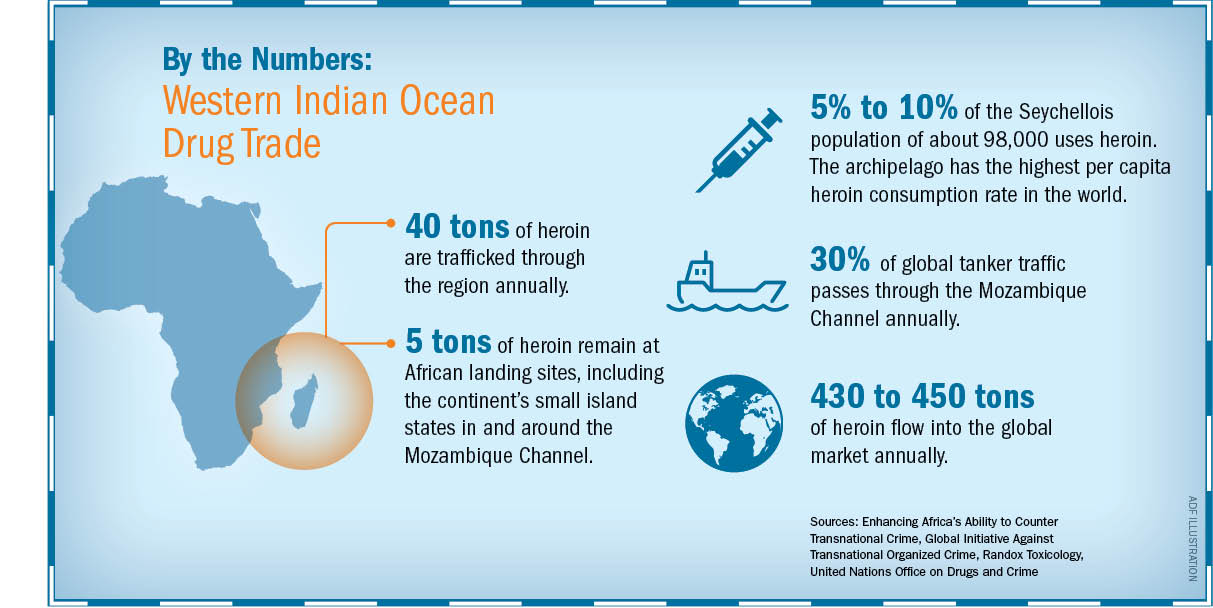

The region’s maritime security challenges have led to dire societal consequences. The Seychelles has the highest per capita rate of heroin use in the world. The region’s other island states face similar challenges, including an influx of cocaine, cannabis, synthetic cannabis, ecstasy and methamphetamine.

“The per capita consumption [of heroin] in Seychelles and Mauritius is crazy,” Yann Yvergniaux, a senior analyst at Trygg Mat Tracking, a nonprofit organization that provides fisheries intelligence to countries and organizations, told ADF. “So many drugs are transmitting that some of it ends up on the local market. Some involved in the trade do recreational drugs. It’s horrible. In Seychelles, some shipping boat owners told me they can’t find young crew members anymore because they’re all on drugs.”

“The per capita consumption [of heroin] in Seychelles and Mauritius is crazy,” Yann Yvergniaux, a senior analyst at Trygg Mat Tracking, a nonprofit organization that provides fisheries intelligence to countries and organizations, told ADF. “So many drugs are transmitting that some of it ends up on the local market. Some involved in the trade do recreational drugs. It’s horrible. In Seychelles, some shipping boat owners told me they can’t find young crew members anymore because they’re all on drugs.”

The islands are in and around the Mozambique Channel — a 1,600-kilometer waterway between Madagascar and East Africa that carries about 30% of global tanker traffic. The waters are a major route for the shipment of heroin to Western Europe from Afghanistan through Pakistan.

Comoros is near the center of the channel’s northern border, and Réunion and Mauritius lie east of Madagascar’s 4,800-kilometer coastline.

The amount of heroin seized along the Indian Ocean trafficking route more than doubled between 2018 and 2019, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Wildlife trafficking also has increased due to widespread poverty and increased demand for exotic animal products abroad.

The IOC’s involvement in the region’s maritime security began in the early 1980s as cocaine and heroin became major revenue sources for drug traffickers. The commission gradually established a network of fisheries and enforcement agencies that exchange information and conduct joint inspections at sea.

“Even if a [suspicious vessel] is in the exclusive economic zone waters in one country, the inspector can be from another country,” Raj Mohabeer, the IOC’s chargé de mission, told ADF. “That way neighboring countries cooperate.”

A ‘Sense of Regional Identity’

Inspections typically are initiated when neighboring states share information such as a vessel’s licensing and noncompliance history.

The IOC collaborates with regional bodies such as the Intergovernmental Authority on Development, the East African Community and the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa under the EU-funded Maritime Security Programme.

“This has been done by IOC but also through FISH-i Africa, which is a mechanism that until recently was basically conducting monitoring and surveillance of island states, but [it also includes] Kenya, Somalia and other states, exchanging information,” Yvergniaux said.

Yvergniaux, a former financial analyst at the IOC, added that a “sense of regional identity” among the smaller island states put them “on the course for regional cooperation earlier than other states on the continent.”

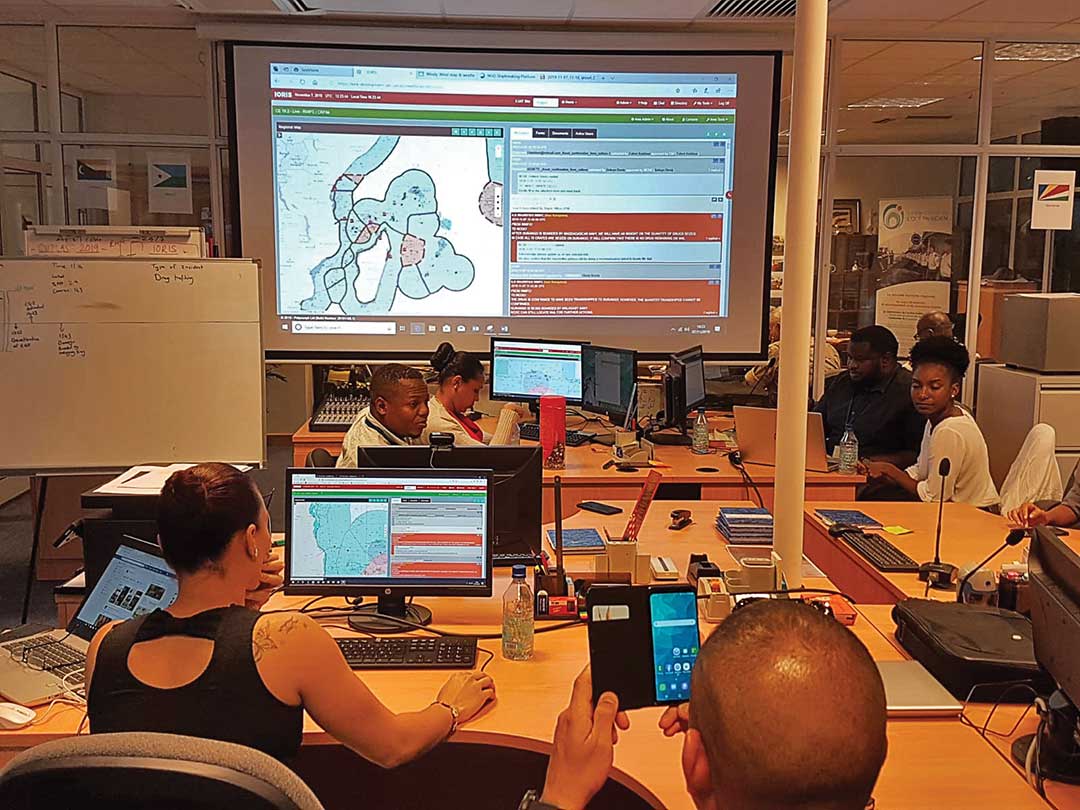

By 2019, the Regional Coordination Operations Centre (RCOC) in the Seychelles, which mainly conducts joint law enforcement actions at sea, was working around the clock with the Madagascar-based Regional Maritime Information Fusion Centre, which shares maritime information and alerts the RCOC of suspicious activity at sea.

Through the IOC-created centers, seven countries have signed agreements to exchange and share maritime information and participate in joint actions on the water: Comoros, Djibouti, Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritius, Réunion and the Seychelles.

“We are in the early stages of establishing architecture for maritime security that will monitor all vessels in the IOC region and analyze the behaviors and identification of the vessels of interest,” Mohabeer said. “If a vessel of interest is something we need to check, we check it. It’s in the early stage of establishing the system, but we’ve already reached far. Unfortunately, COVID-19 came last year and has hampered our progress.”

The IOC continues to encourage East African coastal nations to join.

“We do that because we are talking about common goods like the ocean, but what do you see worldwide?” Mohabeer said. “Few people look at the common good as something they should look at. You have to work for the common good.”

Despite the IOC’s efforts, maritime crime in the region shows no signs of slowing. According to research by ENACT — Enhancing Africa’s Ability to Counter Transnational Crime — an estimated 40 tons of heroin moves through the region annually, and 5 tons remains at landing sites.

In April 2021, Tanzania’s Drug Control and Enforcement Authority and the Tanzania People’s Defence Force seized more than a ton of heroin from a vessel sailing in the Western Indian Ocean just north of Mozambique, The East African newspaper reported. Seven people were arrested.

Later that month, Tanzanian authorities seized 270 kilograms of heroin from a Nigerian man and two Tanzanian accomplices who trafficked the drug by sea. A month earlier, two people were sentenced to life in prison for trafficking in 275.40 grams of heroin hydrochloride in Tanzania, the newspaper reported.

A Template for Continental Africa

A March 2021 report by the Institute for Security Studies argues that the IOC’s efforts to enhance maritime security among the island states could serve as a template for other African nations to follow.

The sharing of maritime information and joint patrols has shown some success in the Gulf of Guinea, where the scourge of illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing is rapidly depleting West African fish stocks and has led to an increase in pirate attacks. The region accounted for 130 of 135 maritime kidnappings globally in 2020.

Authorities formed the Fisheries Committee for the West Central Gulf of Guinea’s West Africa Task Force in 2015 to tackle illegal fishing in the region. Participating nations are Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Liberia, Nigeria and Togo.

The task force is “working on the same basis for sharing license information” as the IOC, Yvergniaux said. “This is still very new. Joint patrols are not happening now, but they’re learning.”