ADF STAFF

Democratic government systems are the overwhelming choice of people in Africa and beyond.

Close to 69% of African people support democratic governance, and more than 75% of the continent’s population rejects military, one-party or one-person rule. The latest Afrobarometer research network survey confirms that most ordinary people remain unflinching in their preference for democracy and the balances on power offered by democratic institutions.

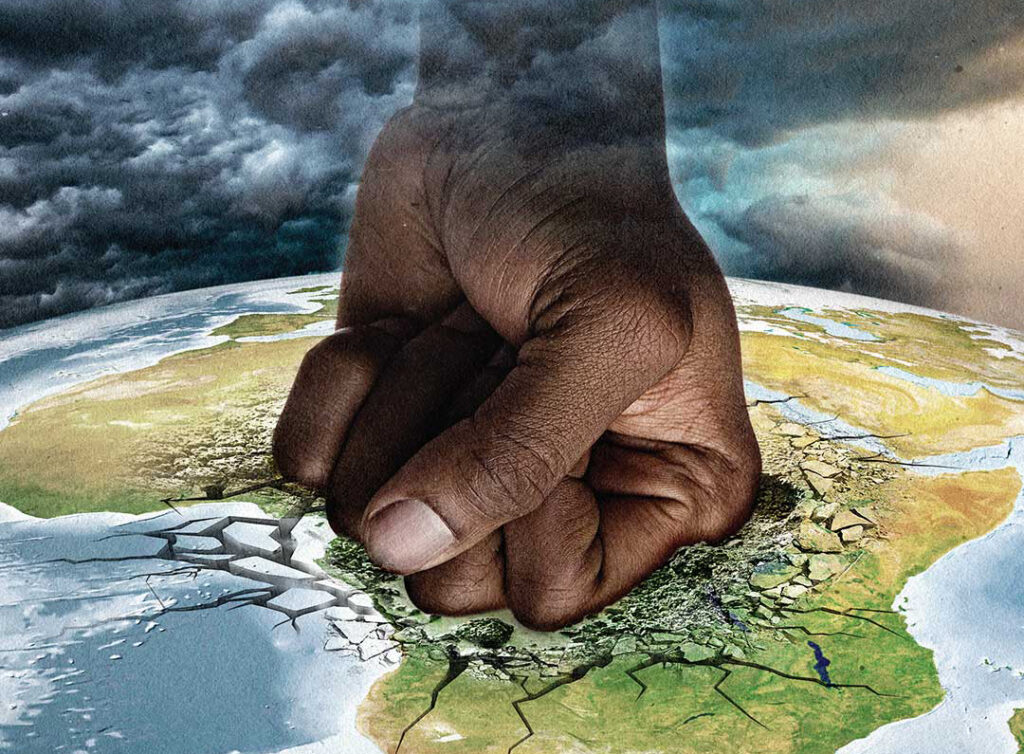

But decades of hard-earned democratic progress have come under attack by the return of military coups, with some leaders advocating for “Big Man” autocratic rule.

Big Man rule can be defined as a form of autocratic governance that is highly personalized and restrained little by institutions such as an independent judiciary, elected representatives, a free press or civil society organizations.

So, what are the hallmarks of this style of rule, and how might it be avoided?

COLONIAL ROOTS

Big Man rule is an outgrowth of Africa’s colonial history, characterized by an appointed leader who did not tolerate dissent. Detractors often were jailed and silenced.

In their 2019 book, “Authoritarian Africa: Repression, Resistance, and the Power of Ideas,” Nic Cheeseman and Jonathan Fisher wrote that colonialism taught traditional leaders that they could operate without checks and balances, and in some cases, without any real claim to leadership. Colonial leaders inspired would-be Big Men to rig elections and invalidate the results if they were not to their liking.

The colonial system often left newly independent countries with few lasting institutions. Instead, it left behind a culture of corruption, coercion, abuse by law enforcement and a disregard for human life. With no playbook for building democracies, the vacuum cleared the way for Big Men to emerge.

In order for an authoritarian leader to survive, he had to implement the same mechanisms of colonial oppression, such as cronyism, corruption, bribery and even violence.

Researchers Camilla Houeland and Sean Jacobs, in a 2016 report, agreed that Big Man rule is a direct product of colonialism.

in 1979. THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

“Colonial administrators utilized African traditional structures for ‘indirect rule,’ but deformed them by promoting the power of the chief or the traditional leader at the expense of the precolonial checks and balances mechanisms,” they wrote. “Post-independence African presidents have just perfected these systems.”

The flaws of the Big Man model serve as a cautionary tale for military coup leaders and juntas seeking to extend their rule. The most common flaws with the model result from a lack of will and/or a capacity to address complex political and economic problems facing the country.

UNCHECKED POWER

Coup leaders and the Big Man find ways to remain in power at all costs. They often use dubious claims of insecurity and election fraud as a means of staying in power. But the longer their grip on power lasts, the more likely they are to become isolated and prone to bad decisions.

“Decades in office can cause a leader to succumb to megalomania or paranoia,” wrote Gideon Rachman for The Guardian in April 2022. “The elimination of checks and balances, the centralisation of power and the promotion of a cult of personality make it more likely that a leader will make a disastrous mistake.”

In his 2020 study, “Breaking the Cycle of Big Man Rule in Africa,” researcher Corey Watson said that for several reasons, such as histories of tribalism and colonialism, Big Man rule has embedded itself in parts of Sub-Saharan Africa.

“Virtually every ruler carefully selects those he is surrounded by based on the potential for loyalty, often at the expense of competence,” he wrote. “This can be family members, members from his tribe, or members from his hometown. Some rulers peacefully play off the ambitions of these loyalists, some pay them off, some rotate them in and out of power, some rule by fear and coercion, and some simply trust them.”

Ultimately, Watson wrote, allegiance to a Big Man comes at a price: “If nobody is being paid for their loyalty to the Big Man, then there is no incentive to remain loyal.”

Researcher Goran Hyden, in describing dictators, said, “Tyrants rule through fear. They reward agents and collaborators and turn them into mercenaries. Tyranny, in short, is marked by particularly impulsive, oppressive, and brutal rule that lacks elementary respect for the rights of persons and property.”

BAD ALLIANCES

International, continental and regional isolation results in limited diplomatic options for the Big Man. When operating on the global stage, he finds few partners available. This plays into the hands of some global powers that are eager to strike deals with pariah regimes. In recent years, Russia has sought to build alliances with autocratic regimes in Africa, offering weapons and mercenary manpower in exchange for access to natural resources and other favors.

“The Kremlin has focused on wooing elites: the warlords, generals and Presidents for life whose personal desires are simpler and cheaper to satisfy than the needs of their people or their economies,” Simon Shuster wrote for Time magazine.

As the bond deepens, the autocrat becomes more dependent on the alliance to remain in power. This increases the leverage a country such as Russia has and the control it can exert.

DECAYING INSTITUTIONS

The ruling style of the Big Man does not tend to lead to an efficient government. In order for autocratic governments to endure, they must rely on bribery, corruption, cronyism and violence. This can have far-reaching effects on the present and future civil society efforts at self-governance.

The daily management and decision-making of many state institutions are outside the educational background of most autocratic strongmen. Areas such as sanitation, education, power generation, finance, monetary policy, trade and investment require higher education and experience that are not found in military schoolrooms.

Corruption tends to flourish in this environment. The autocrat rewards loyalists with appointments to powerful posts, and the appointee, in turn, seeks to enrich himself from his position of authority.

In its 2019 report on Sub-Saharan Africa, Transparency International (TI) pointed to authoritarianism as a significant factor in creating a corrupt environment.

“While a large number of countries have adopted democratic principles of governance, several are still governed by authoritarian and semi-authoritarian leaders,” TI reported. “Autocratic regimes, civil strife, weak institutions and unresponsive political systems continue to undermine anti-corruption efforts.”

Although TI found that the highest performing countries — Botswana, Cabo Verde and the Seychelles — tended to have vibrant democracies and strong institutions, the lowest performers had other characteristics linked to conflict and authoritarianism.

“Many low performing countries have several commonalties, including few political rights, limited press freedoms and a weak rule of law,” TI reported. “In these countries, laws often go unenforced and institutions are poorly resourced with little ability to handle corruption complaints. In addition, internal conflict and unstable governance structures contribute to high rates of corruption.”

FRAUDULENT ELECTIONS

One particularly powerful asset Big Men have is that electoral systems operate at their discretion.

“In practice, the president makes the rules, breaks them and changes when he wants to,” wrote Houeland and Jacobs. “… Who controls the count, wins the election and in the lead-up, the police and the army harass and intimidate the opposition, while the president campaigns uninterrupted. Furthermore, equating popular will with the president’s person is key. The president is always patriotic, and it is only the president who is willing and able to do what is needed.”

In such scenarios, the presidency can become a family business, as there is no future or monetary gain outside politics. Accumulating wealth and business opportunities are tied to controlling the state. Once a Big Man is out of office, he loses the ability to steer contracts or get a cut from profits. After tenure, the former president and his allies risk prosecution either for embezzlement or human rights abuses.

There is an incorrect perception that many people in African countries value development over democracy and are willing to trade away political rights for a ruling Big Man who can get things done. This belief, according to Cheeseman and historian Dr. Sishuwa Sishuwa, has proved to be “durable, despite being wrong.”

Drawing on survey data collected between 2016 and 2018, Cheeseman and Sishuwa concluded that “strong majorities” in African countries think that democracy is the best political system. The study found widespread support for a form of consensual democracy that “combines a strong commitment to political accountability and civil liberties with a concern for unity and stability.”

“It is both misleading and patronising to suggest that democracy has somehow been imposed by the international community against the wishes of ordinary people,” the authors wrote. “Instead, it has been demanded and fought for from below.”

FOUR KEYS TO PREVENTION

Cheeseman, a professor at the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom, says there are four key things that a country must have to prevent Big Man rule.

• It must develop institutions that can be autonomous from the executive. “This is hard, but it can be done,” he told ADF via email.

• The population must be educated. “Free primary education has been a boost for democracy, but increasing the quality and duration of education would be good,” he noted.

• An independent middle class that does not depend on government employment and contracts is necessary. The country also must have centers of economic power, such as independent business owners who are not allied to the ruling party.

• It must build a tradition of democracy. When people are invested in their democracy because of a shared history and sacrifice, they’re more inclined to stay vigilant and protect it. “Democracies need founding myths, moments that people come out and protest and force change,” Cheeseman wrote.