The Mosquito-Borne Disease Is a Continental Problem, but a Program is Equipping African Militaries to Fight It

ADF STAFF

An insidious, debilitating force has attacked tiny Burundi, in Africa’s Great Lakes region.

Since the beginning of 2015, there have been 16.8 million cases of malaria reported in the country, according to the United Nations. More than 7,800 people have died in that period, and many more may face a lifetime of relapses and illness, depending on the strain of the disease and the level of treatment they received.

The crisis, which officials labeled an epidemic, is a crushing blow to a nation already reeling from political turmoil stemming from President Pierre Nkurunziza’s pursuit of a third term in office in 2015. Hundreds of thousands of Burundians have fled the nation to escape violence and human rights abuses.

Dr. Josiane Nijimbere, Burundi’s minister of public health, told The East African the outbreak of the mosquito-borne disease can be attributed to an increase in marshland for growing rice and the improper use of protective mosquito netting.

Climate change also has exacerbated the problem. “There is a strong association between malaria and warm temperatures, which have led to significant increase in malaria cases because of the spread of mosquitoes,” Nijimbere told reporters in March, according to the Voice of America.

A CONTINENTAL PROBLEM

Burundi is not alone. Malaria is prominent in nations across the continent, from Ghana to Ethiopia, and virtually everywhere in between.

Four primary parasite species cause malaria and are spread from person to person by female Anopheles mosquitoes. Two parasites — P. falciparum and P. vivax — pose the most significant human health threat in Africa. P. falciparum is the most prevalent and kills the most people.

Malaria prevention consists mainly of using insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) and indoor spraying to keep mosquitoes away from people, the World Health Organization (WHO) reports. Treatments include drugs to prevent infection and prompt diagnosis and treatment for those who become infected. Often, if detected early and treated quickly with the proper drugs, malaria can be cured.

Malaria prevention consists mainly of using insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) and indoor spraying to keep mosquitoes away from people, the World Health Organization (WHO) reports. Treatments include drugs to prevent infection and prompt diagnosis and treatment for those who become infected. Often, if detected early and treated quickly with the proper drugs, malaria can be cured.

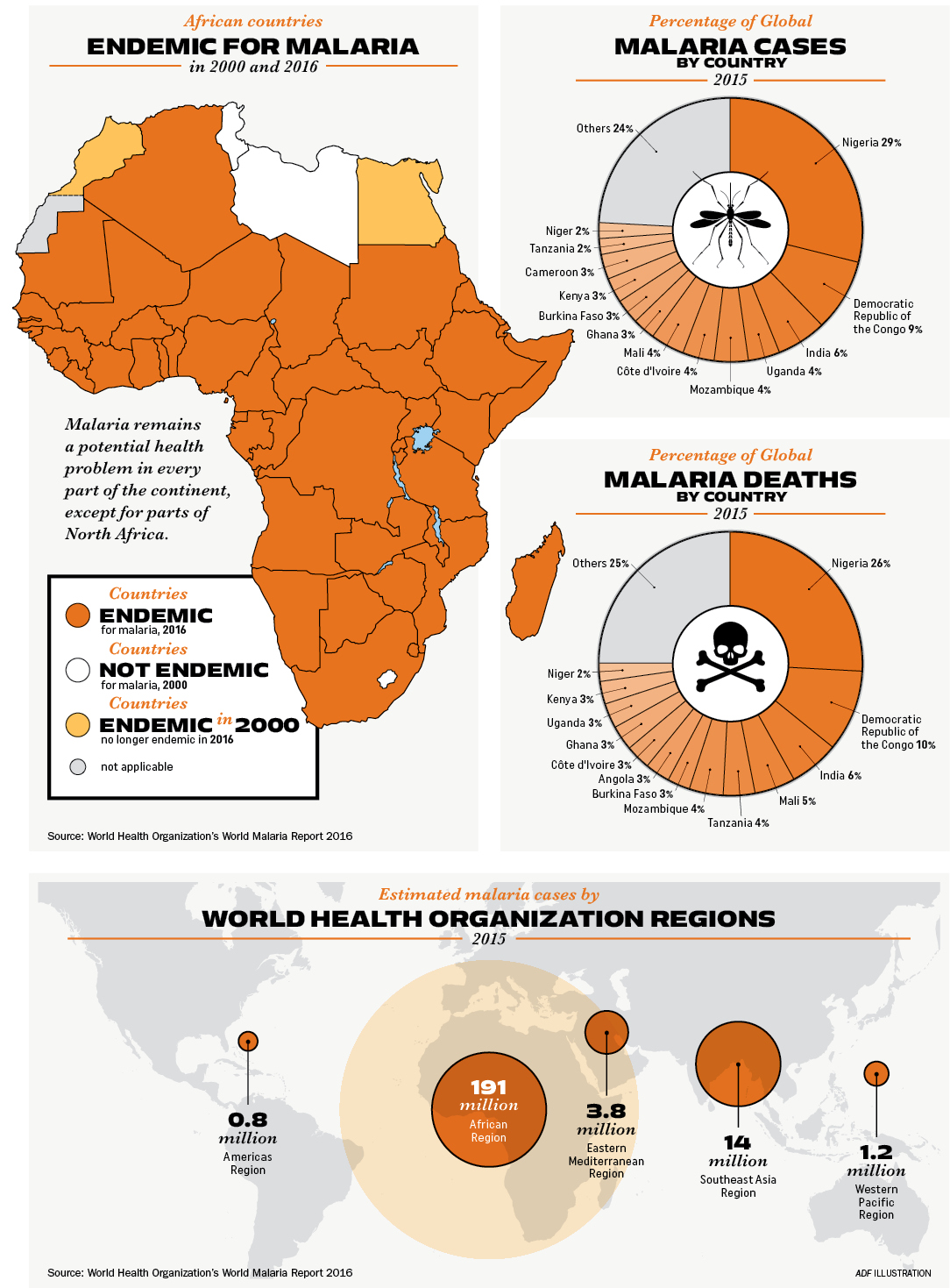

Despite these preventive techniques and treatments, the outbreak in Burundi is indicative of a persistent threat in Africa. Most of the continent is prone to malaria, and the disease still strikes millions there annually. WHO estimated that in 2000 there were 214 million cases of malaria in Africa alone, resulting in 764,000 deaths.

The good news is that by 2015, the number of cases and deaths had fallen to 191 million and 394,000, respectively, according to a 2016 WHO report. That’s a 48 percent decrease in deaths, due in large part to the growing use of ITNs. Despite improvements, malaria remains the pre-eminent health concern on the continent, far surpassing even the deadly, but comparatively rare, Ebola.

Cape Verde, Mauritius and Tunisia, have made significant strides toward ridding themselves of malaria over the years, but much work still needs to be done all over the continent.

Maj. Joseph Tamba Gayflor, commander of the Armed Forces of Liberia’s (AFL) Medical Command, told ADF via email that malaria is a major cause of outpatient visits to AFL health centers. “Many Soldiers are withdrawn from their duties due to illness associated with malaria,” he said. “The main burden of the disease is associated with family, especially children under 5 and pregnant women. This also impacts the psychological preparedness of Soldiers, which prevents them from being mission focused. Additionally, in peacekeeping missions, malaria is the major cause of morbidity.”

The AFL educates its Soldiers and their dependents on how to prevent malaria by using ITNs and anti-malarial drugs, Gayflor said.

One program is helping experts in African nations develop their ability to quickly and accurately diagnose malaria and better identify the vectors that transmit it and other diseases.

THE AFRICA MALARIA TASK FORCE

In 2011, senior leaders from five East African nations gathered in Stuttgart, Germany, for a command surgeon malaria symposium sponsored by U.S. Africa Command. These leaders from Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda discussed strategies for addressing malaria and called for tactical level information sharing. Events focused on diagnostics and entomological issues such as vector surveillance and mosquito identification. Two other countries — Djibouti and South Sudan — have since joined in East Africa.

Two years later, identical efforts kicked off in West Africa with Benin, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Liberia, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal and Togo. Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea and Sierra Leone have since joined in that region.

The Africa Malaria Task Force (AMTF) sponsored 17 events between 2011 and March 2017, which include diagnostic and entomological symposia. A diagnostic symposium in Ghana involved 18 African nations, with two participants per nation. Two-week diagnostic events include makeshift field laboratories with testing kits, microscopes, computers and projectors. After a pretest to gauge knowledge, participants take part in basic microscopy and basic and advanced diagnostic techniques. They learn the steps of diagnosing malaria and see its similarities and differences compared to other vector-borne illnesses. Participants receive booklets and CD-ROM slide libraries so they can refer to images after they return home. Often, they form their own social media circles and share information long after sessions have ended.

In the two-week entomological information-sharing sessions, participants go out into the field for “tick drags,” in which a white cloth is drawn through vegetation to collect insects and arachnids. Participants also trap mosquitoes and identify them to determine what disease vectors might be present. Properly identifying vectors can help with diagnostics, even if sophisticated equipment is unavailable.

For example, if a person shows symptoms that resemble malaria but mosquitoes that carry the disease have not been found in that area, that is a clue to consider other diseases with similar symptoms.

The AMTF also tries to meet with senior leaders yearly to discuss what has been going on at tactical events. They ask for suggestions on how to improve symposia and seek guidance on future events. This gives high-ranking officers from participating countries a chance to have a say in programming and tailor information to their forces’ needs.

Gayflor said the AFL has participated in AMTF events in Ghana, Kenya and Nigeria. So far, five AFL members have taken part in diagnostic, entomology, and clinical and laboratory technician sessions. Liberian forces have learned prevention strategies and exchanged ideas with personnel in other countries. “There is a need to continue support from the AMTF, in terms of training and equipping militaries to combat the disease,” he said.

BEYOND THE MILITARY

In 2018, the AMTF expects to offer question-and-answer sessions between events to help participants maintain their skills. Organizers will send out midterm tests and slides and get back answers. If tests show that skills have not been maintained, participants can get help before they attend another information-sharing event.

The information-sharing sessions engage primarily with military personnel, which helps ensure their military’s readiness to prevent, diagnose and treat malaria within its ranks. This also helps maintain a robust, healthy military that is prepared to respond when needed. But the program also has a civilian goal. In many African countries, the military supports its nation’s civilian population. Organizers knew that equipping African militaries to diagnose and treat malaria would benefit populations living near garrisons.

Techniques shared in AMTF sessions offer another valuable benefit as well: They can be applied to many vector-borne diseases. Africa is home to a number of diseases spread by mosquitoes: malaria, yellow fever, dengue fever, West Nile virus and Zika virus.

The potential dangers of these additional vector-borne risks were underscored in late 2015 and into 2016. A yellow fever outbreak was detected in Angola in December 2015, and the viral disease spread throughout the country and into the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in March 2016, WHO reported. Angola reported 4,306 suspected cases, and the DRC reported 2,987 suspected cases. In all, about 400 people died.

“Malaria — yes, it’s a significant threat — but there are other threats out there,” said U.S. Air Force Maj. Antonio Leonardi, a public health officer with U.S. Africa Command. “You’re not going to know what they are until you start looking for them, and the process is still the same.”

Kenya, Ghana, Malawi chosen for Malaria Vaccine Trial

THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Three African countries have been selected to test the world’s first malaria vaccine, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced on April 24, 2017. Ghana, Kenya and Malawi will pilot the injectable vaccine in 2018 with hundreds of thousands of young children, who have been at the highest risk of death.

The vaccine, which has partial effectiveness, has the potential to save tens of thousands of lives if used with existing measures, according to Dr. Matshidiso Moeti, WHO regional director for Africa. The challenge is whether impoverished countries can deliver the required four doses of the vaccine for each child.

Malaria remains one of the world’s most stubborn health challenges, infecting more than 200 million people every year and killing about half a million, most of them African children. Bed netting and insecticides offer the best protection.

A global effort to counter malaria led to a 62 percent cut in deaths between 2000 and 2015, WHO said. But the United Nations agency has said in the past that such estimates are based mostly on modeling and that data is so unreliable for 31 countries in Africa — including those believed to have the worst outbreaks — that it couldn’t tell whether cases have been rising or falling in the past 15 years.

The vaccine will be tested on children 5 months to 17 months old to see whether the protective effects shown so far in clinical trials can hold up under real-life conditions. At least 120,000 children in each of the three countries will receive the vaccine, which has taken decades of work and hundreds of millions of dollars to develop.

Ghana, Kenya and Malawi were chosen for the vaccine pilot because all have strong prevention and vaccination programs but continue to have high numbers of malaria cases, WHO said. The countries will deliver the vaccine through their existing vaccination programs.

WHO is hoping to wipe out malaria by 2040, despite increasing resistance problems to drugs and insecticides used to kill mosquitoes.

“The slow progress in this field is astonishing, given that malaria has been around for millennia and has been a major force for human evolutionary selection, shaping the genetic profiles of African populations,” Kathryn Maitland, professor of tropical pediatric infectious diseases at Imperial College London, wrote in The New England Journal of Medicine in December 2016. “Contrast this pace of change with our progress in the treatment of HIV, a disease a little more than three decades old.”

Pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline developed the malaria vaccine. The $49 million for the first phase of the pilot is being funded by the global vaccine alliance GAVI, UNITAID and Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

Diseases Spread By Mosquitoes in Africa

ADF Staff

Vector-borne diseases are transmitted by the bite of an insect or arachnid such as mosquitoes, ticks and certain species of flies. Mosquitoes spread a number of diseases in Africa, including the following, according to the World Health Organization:

DENGUE FEVER:

Dengue is prevalent in the tropics and is endemic in more than 100 countries in Africa, the Americas, the Eastern Mediterranean, Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific. Data is not available for the number of cases in Africa, but the Americas, Southeast Asia and Western Pacific regions are the most seriously affected.

Symptoms: The mosquito-borne virus exists in four strains, causes severe flu-like symptoms and can be lethal. People can recover and acquire immunity for the strain that infected them.

Vector: Aedes aegypti mosquito

YELLOW FEVER:

This virus is endemic in 33 African countries and 11 South American countries. An outbreak began in Angola in December 2015 and spread to the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Symptoms: Symptoms can include sudden fever, chills, severe headache, muscle pain, nausea, vomiting and fatigue. After a brief remission, a small percentage will develop severe symptoms, such as high fever, jaundice, bleeding, and eventually organ failure.

Vector: Aedes or Haemagogus species mosquitoes

ZIKA VIRUS:

Outbreaks of this mosquito-borne virus have been recorded in Africa, the Americas, Asia and the Pacific. Seventy countries and territories have reported evidence of Zika transmission since 2007.

Symptoms: Symptoms can include mild fever, a skin rash, conjunctivitis, muscle and joint pain, malaise or headache. Zika can cause microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Vector: Transmitted primarily by Aedes mosquitoes

CHIKUNGUNYA:

Chikungunya has been identified in more than 60 countries and occurs mostly in Africa, Asia and on the Indian subcontinent. However, a 2015 outbreak affected several countries in the Americas.

Symptoms: Chikungunya causes an abrupt onset of fever, which often includes joint pain, muscle pain, headache, nausea, fatigue and a rash. Joint pain can be severe and last for weeks. It shares clinical characteristics with dengue fever and Zika. Most patients recover, but joint pain has been known to persist long term. Eye, neurological, heart and gastrointestinal issues occur occasionally.

Vector: Most commonly female Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes

WEST NILE VIRUS:

About 80 percent of all people who contract West Nile virus will never show symptoms, but it can cause a fatal neurological disease. The virus can cause severe disease and death in horses. Vaccines are available for horses but not people. Birds are the natural hosts of West Nile virus.

Symptoms: Fever, headache, tiredness, body aches, nausea and vomiting sometimes are accompanied by a skin rash and swollen lymph glands.

Vector: Culex mosquitoes, particularly Culex pipiens