Pharmaceuticals Are Not Always What They Seem

ADF STAFF

Dolphin Anyango of Kenya woke up to find that an infection around her left eye had begun to swell. She knew she needed medicine to treat it, but she did not have time to go to a hospital. So she went to a local pharmacist instead in Nairobi’s Kibera neighborhood and got some medicine.

“After taking the medicine for two days, I thought it was going to stop the swelling,” she told a BBC reporter in 2018. “But unfortunately, it swelled more than the way it was before. The wound here in my face was very horrible,” she said as she rubbed her left cheekbone. “After two days I took my medicine to the doctor. The doctor told me that I was given the wrong medicine. After the doctor gave me his medicine, now, in hospital, that is when I started seeing the improvements in my eye.”

In Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, Moustapha Dieng began to have stomach pains, so he went to a doctor. The doctor prescribed a malaria treatment, but it cost too much for the 30-year-old tailor, so he went to an unlicensed street vendor to find cheaper pills.

Within days, he was hospitalized after the drugs he bought made him sick, Reuters reported. One night in the hospital cost Dieng twice what he would have paid for the legitimate drug that his doctor prescribed.

In Nigeria in 2009, more than 80 children were killed by a teething syrup that had been tainted with a chemical used in automobile engine coolant, according to Reuters.

All of these stories point to a larger problem on the continent: Fake, tainted, expired, spoiled and poorly packaged medicines are sickening — and even killing — people each year.

Counterfeit pharmaceuticals alone are a $30 billion industry, according to a November 2018 BBC report. That figure nearly tripled in five years’ time. At least one estimate says fake drugs are a $200 billion industry.

A 2017 World Health Organization (WHO) study estimated that one out of every 10 medical products in low- and-middle-income nations is fake or substandard, according to ENACT, a European Union-funded crime research group.

The problem presents an intractable challenge for African authorities, despite ongoing efforts to stanch the flow of these pharmaceuticals to the continent.

THE SIZE OF THE PROBLEM

Fake pharmaceuticals are a huge problem for many nations in Africa, and not only when measured in dollars lost from the sale of legitimate medicines. The problem has a significant impact on public health. A November 2018 report from ENACT indicated that counterfeit medicines may lead to as many as 158,000 avoidable deaths a year, just from malaria.

Multiple operations aimed at getting fake medicines off the streets have taken place in recent years, and each one seems to find an abundance of contraband flowing into the continent.

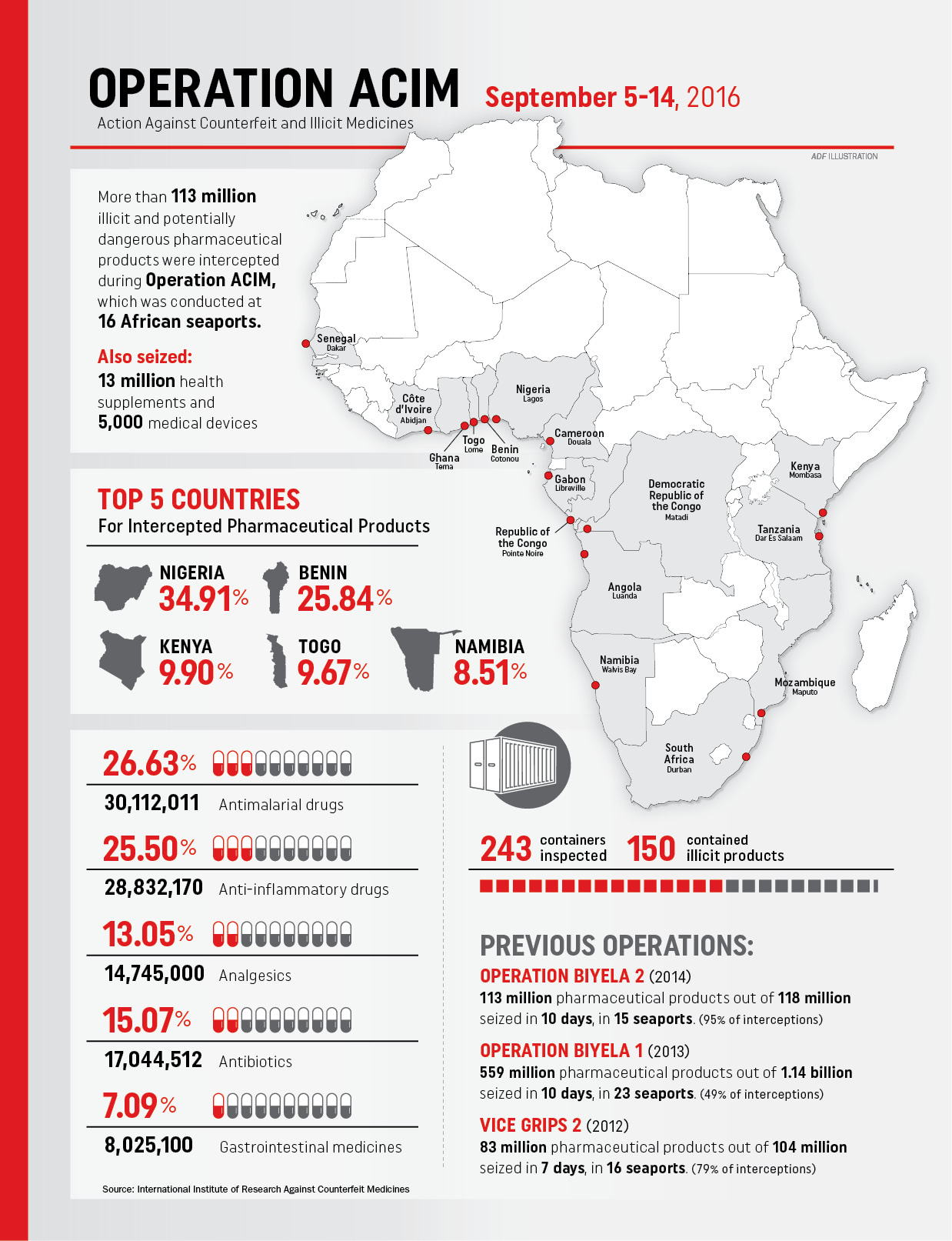

From August 31 to September 14, 2016, officials from the World Customs Organization (WCO) and the International Institute of Research Against Counterfeit Medicines (IRACM) launched Operation ACIM (Action Against Counterfeit and Illicit Medicines). The effort began with three days of training in Mombasa, Kenya, and then 10 days of customs interceptions in 16 seaports in 16 Sub-Saharan nations.

ACIM intercepted 129 million units of all kinds. Of those, 113 million were illicit or counterfeit medicines, including nearly 250,000 veterinary products, 13 million health supplements and 5,000 medical devices.

The biggest interceptions were made in Benin, Kenya, Namibia, Nigeria and Togo. Seized medicines included antimalarials, antibiotics, anti-inflammatories, analgesics, as well as about 2 million doses of anti-cancer drugs. Three-quarters of the medicines came from India. The rest originated in China.

The 2016 operation was the latest of four by WCO and IRACM. Together with the similar busts in 2014, 2013 and 2012, authorities seized nearly 900 million counterfeit or illicit medical products valued at about $444 million.

Perhaps the most striking statistic to come out of those four operations is that they together represent only 37 days of enforcement out of four years’ time, and each dealt with only 15 to 23 seaports.

WHO differentiates between substandard medical products and false ones. Substandard products are those that are out of specification and deemed “as ostensibly authorized medical products that fail to meet manufacturing, supply or distribution quality standards,” according to ENACT. “Unregistered or unlicensed medical products are those which have not undergone evaluation or approval by the relevant regulatory bodies.”

Falsified products “purposefully conceal or lie about their identity, composition or source,” ENACT says. This can mean that they are contaminated, falsely claim to have an active ingredient or have that ingredient in the improper amount.

As thousands of people die and billions of dollars are wasted in Africa due to fake and substandard medicines, corporations and national governments are looking at a range of technological solutions to combat the problem.

In one approach, global tech giant IBM is working with blockchain technology to keep fake drugs out of the legitimate supply chain. The technology would allow medicines to be tracked step by step from the source to the end user so that consumers can be assured that they have legitimate drugs.

Blockchain technology is relatively new and holds promise for a number of sectors, chiefly the financial and health industries. The trade of cryptocurrency bitcoin already depends on blockchain technology, for instance.

Generally speaking, blockchain is “an incorruptible digital ledger of economic transactions that can be programmed to record not just financial transactions but virtually everything of value,” according to Don and Alex Tapscott, authors of Blockchain Revolution: How the Technology Behind Bitcoin and Other Cryptocurrencies Is Changing the World.

IBM Research in Haifa, Israel, has developed a way to use blockchain to track, trace and authenticate drugs from the drug company to the patient, and every stop in between. According to a video produced by IBM, the process can verify what is delivered, by whom, to whom, when, and where for African doctors, pharmacists and consumers.

The process involves a trusted network that lets different parties store information that only authorized members can see and that can’t be altered once entered. In pharmaceutical orders, the process can:

- Verify that authentic medicines are handed to authorized persons at every transfer point.

- Guarantee compliance with proper transportation and asset transfer conditions.

- Ensure that a joint verified transactions ledger is always available.

The IBM process can be operated through mobile phones and gives each authorized party in the network a way to initiate, finish, track and verify transactions. Here is an example of how the process would work:

- A doctor, needing a particular drug, checks prices at local pharmacies and orders from one. She sets up the order and delivery using blockchain.

- The pharmacist receives the order and registers it in the blockchain. He then prepares the delivery and scans drug QR codes and serial numbers for the blockchain.

- The pharmacist selects a delivery carrier from those available on the blockchain system. The carrier, motivated to perform well because his reputation is based on customer ratings, heads to the pharmacist and authenticates to the blockchain. The pharmacist initializes the delivery; the carrier checks serial numbers and QR codes and accepts delivery.

- The process is electronically appended to the blockchain ledger after the provider and carrier verify that they are physically present at the pharmacy.

- The carrier leaves with the drug. If a refrigerated container is necessary, that container will send out periodic signals with any alarms saved in the blockchain for review later.

- The carrier arrives at the doctor’s clinic. He and the doctor authenticate using the blockchain. The doctor verifies the tracking code number of the delivery and scans and verifies the drug QR code.

- The doctor accepts the delivery, and the carrier accepts the delivery transfer, which is appended to the blockchain. The drug now is shown at its final destination. The pharmacist is able to electronically verify that the transaction was completed successfully.

IBM is not the only company looking to work with African countries on blockchain solutions. A company called MediConnect met with Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni and Minister of Health Dr. Jane Ruth Aceng in July 2019 to discuss the blockchain solution it is developing to identify and remove counterfeit medicines from the supply chain.

In Ghana, entrepreneur Bright Simons developed the phone-based mPedigree system. It works with drug companies to put a unique code on medicine packages. Consumers can text the code from the packaging to a predetermined phone number. That code is checked against authentic codes stored in the cloud. The consumer then receives a text message indicating whether the drug is genuine. The system has since expanded elsewhere in Africa and Asia, according to mHealth Knowledge.

Kenya also is moving forward with a process that will let customers use their mobile phones to determine whether medicines are genuine, according to the Daily Nation. The process will use codes sent by text message to identify quality and track medicines across the supply chain. Consumers in Kenya also can use SMS codes to identify legitimate pharmacies and pharmacists.

“Deployment of new technology to help track the drugs is the only solution, seeing that the criminals are always a step ahead of us,” said Fred Siyoi, registrar and chief executive of Kenya’s Pharmacy and Poisons Board. “So we have to rely on technology to nab them.”