ADF STAFF

The cranes that unload containers from ships at two of South Africa’s busiest ports slowed nearly to a halt in July 2021. Trucks waited in line for 14 hours or more to pick up cargo. Ships were forced to anchor outside the harbor for days and decide whether to skip the affected ports altogether. Shop owners and consumers worried about empty shelves as a prime shopping season approached.

“This could not have come at a worse time,” Denys Hobson, logistics and pricing analyst at the South African bank Investec, said. “If nothing can move in and out the country, there will be serious economic ramifications.”

The disruption was caused by a cyber-attack. Hackers had infiltrated the network of Transnet, the state-owned company that operates the ports at Durban, Cape Town and others, as well as South Africa’s railway and pipeline network. Unable to fulfill contractual obligations for more than a week, the company was forced to break its contracts until the attack was resolved.

News reports stated that “Death Kitty,” a group of hackers based in Eastern Europe or Russia, took credit for the attack, which used a technique commonly referred to as ransomware, because it freezes a computer system until a ransom is paid.

It was the most severe attack ever perpetrated on South Africa’s critical infrastructure, but experts warn it will not be the last.

“Attacks on critical infrastructure, including maritime ports, are likely to increase in severity and quantity,” wrote Denys Reva for the Institute for Security Studies. “The economic toll for African states will inevitably be high, which means that measures to boost cyber security and protect infrastructure are vital.”

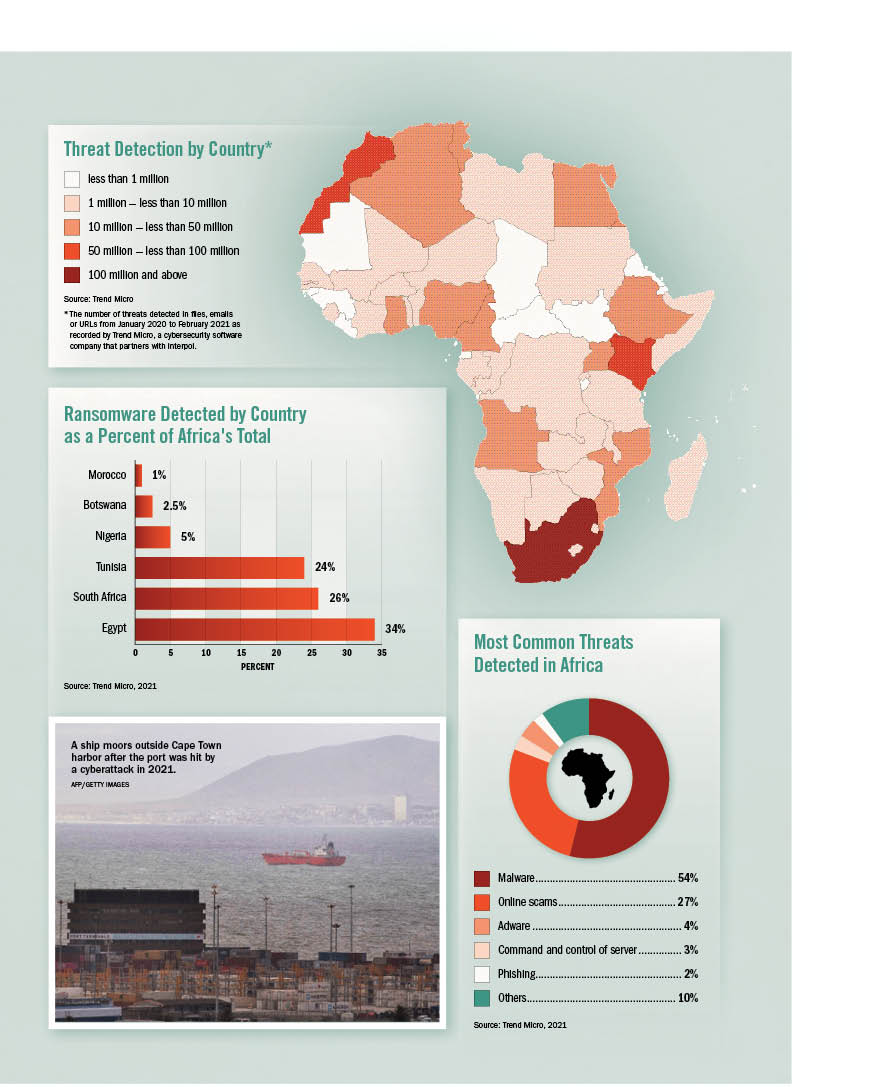

In the first quarter of 2021, South Africa was hit harder by ransomware attacks than any country on the continent, according to Interpol’s African Cyberthreat Assessment Report.

Government agencies are among those most at risk.

In September 2021, an attack forced South Africa’s Department of Justice and Constitutional Development to shut down its information technology (IT) system, which stores information including personnel files. In a separate incident the same year, the National School of Government had to shut down its IT system for two months, which cost the government training institution about 2 million rand. Even the nation’s president was affected by hackers who infiltrated his phone.

Cybersecurity experts warn that South Africa’s government institutions are now squarely in the crosshairs of hackers.

“The combination of aging technology, inadequate funding, and lack of training, coupled with the high-value data these organisations hold, makes them a goldmine for bad actors,” wrote Saurabh Prasad for South Africa’s IT-Online.

Interpol found that African organizations saw a 34% jump in ransomware attacks in the first quarter of 2021, the highest recorded anywhere in the world. Government institutions have fallen behind in the race to protect their IT infrastructure and must catch up, Prasad said.

“The threat landscape is also evolving far faster than the ability of government organisations to keep up with technology, which makes it an easy, profitable and therefore very attractive target,” Prasad wrote.

State-Backed Cyberwar

Although it is not known whether any nation or its proxies were behind the Transnet attack, state-backed hacking is a growing threat in Africa.

In 2018, Chinese-backed hackers stole emails and surveillance data from servers in the African Union headquarters in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. In 2017, North Korea-backed hackers conducted a global attack known as Wannacry, which paralyzed businesses and public institutions in 150 countries. In 2020, Egyptian hackers hit Ethiopian businesses and governmental agencies in an attempt to disrupt construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.

In 2021, Google sent more than 50,000 warnings to account holders worldwide telling them they had been the target of government-backed phishing or malware attempts. One of the most prolific perpetrators globally is a group known as APT35 or “Charming Kitten,” which has links to Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

African nations are particularly vulnerable to outside interference. Chinese companies built about 80% of the continent’s telecommunications networks. The telecom company Huawei, which has strong ties to the Chinese Communist Party, is positioning itself to build much of the continent’s 5G network. Additionally, Chinese companies have built IT systems in at least 186 government buildings in Africa, including presidential palaces, defense ministries and parliamentary buildings, according to a Heritage Foundation report.

Experts say this infrastructure means Chinese-aligned spies would have little trouble accessing sensitive government data.

“The Chinese government has a long history of all types of surveillance and espionage globally,” said Joshua Meservey, senior policy analyst for Africa at the Heritage Foundation. “So we know this is the sort of thing they want to do, the sort of thing they have the capacity to do. And also, Africa is important enough to them to do it.”

There are several strategic moves African countries can take to protect themselves from cyberattacks. Here are some:

Build Safeguards as You Go

As nations conduct more business online and sectors such as transportation, water and power are controlled digitally, hackers see openings to cause damage. Countries with the highest rates of internet penetration tend to be the most vulnerable. In one way, this is an advantage for African countries because many were relatively slow to adopt digital technology. This gives them the opportunity to build in safeguards as they develop their IT infrastructure.

Researchers Nathaniel Allen of the Africa Center for Strategic Studies and Noëlle van der Waag-Cowling of Stellenbosch University in South Africa said developing countries are not burdened by the older software architecture or “legacy code” that is easiest to attack.

By establishing good practices early on, countries that are less digitally advanced can “leapfrog” more cyber-mature countries, Allen and Waag-Cowling wrote.

Diversify Suppliers, Build Domestic Capacity

Countries that rely heavily on a single external service provider could be leaving the door open to state-backed hacking. By one estimate, Huawei manufactured 70% of the 4G base stations used on the continent. The company also is a leader in surveillance and facial recognition systems sold in Africa.

As Chinese-backed infrastructure projects have proliferated across the continent, they often are paired with IT development, which links control over multiple sectors, such as water, power and transportation.

“This could potentially create backdoors and vulnerability pathways,” Waag-Cowling wrote in an article for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). “The net result is the possible future loss of de facto sovereign control of communication, energy, transport or water infrastructure.”

Experts have encouraged African countries to cultivate relationships with a diverse range of IT service providers to avoid the single-provider pitfall. Competition not only challenges state-backed hacking; it also leads to better service for customers.

Many African countries also are trying to cultivate domestic capacity in the IT sector. Safaricom, the largest mobile phone company in Kenya, and South Africa’s MTN are prime examples of this.

Eliminate Single Points of Failure

Cyber experts bemoan that too many IT systems controlling critical national infrastructure have a single point of failure. This means that if one server, one network or one plant is hit by an attack, an entire country can be left without a vital service, such as water or electricity. Advocates urge African countries to build in redundancies or backup systems to avoid catastrophic service loss in an attack.

“One attack on a single point of failure could lead to the disruption or destruction of multiple vital systems in the country directly affected, and a ripple effect worldwide,” the United Nations and Interpol said in a “Compendium of Good Practices” to protect against cyberattacks. “This creates an appealing target to those intending to harm us. And as our cities and infrastructure evolve, so do their weapons.”

Invest in Detection/Offensive Capabilities

Many nations are investing in computer emergency response teams that can monitor important national networks and critical infrastructure. These are sometimes called the nation’s first responders in the event of a cyberattack.

Some countries, such as Nigeria, are launching cyber commands within the military. Experts say it is important for these commands to develop defensive and offensive capabilities that allow them to protect against attacks and degrade something that poses a threat before it can launch an attack.

The AU has taken a leadership role in encouraging cyber capacity with its Cybersecurity Expert Group, but observers are calling for more regional cooperation. Waag-Cowling said African countries could think of it like “cyber peacekeeping” through which nations work together to shore up cybersecurity at its weakest points. She believes the military, particularly its youngest, most educated cohorts, can play a lead role.

“African armed forces’ ongoing experience with persistent irregular conflict could provide a platform for pivoting towards hybrid warfare threats,” Waag-Cowling wrote for ICRC. “A young, urbanizing and tech-savvy population must complement future cyber defence strategies.”

The stakes are high. If African countries are perceived as soft targets, hackers will attack them, Waag-Cowling warned.

“Cyber defence is, to an extent, reliant on attackers believing that there is sufficient indication of a State’s ability to respond to attacks,” she wrote. “Essentially, the power of a State lies within the perception of its power. A demonstrated and deepened commitment to advancing continental cyber security efforts is therefore required. The future prosperity of Africa and the safety of her people depend on this.”