ADF STAFF

Students at the Government Science College in Nigeria’s Niger State were sleeping one night in February 2021 when more than 50 gunmen from a nearby forest raided the campus, with only a single guard to offer resistance.

Even though a police station was less than 3 kilometers away, the invaders roamed the campus for three hours without interference. They fled back to the forest, taking 42 hostages, most of them boys about 15 years old, according to The Africa Report magazine.

The invasion sparked a national uproar. It was similar to the kidnappings of 276 Chibok girls by the extremist group Boko Haram in 2014, the kidnappings of 317 girls from a secondary school in Zamfara State in February 2021 and other hostage situations in Nigeria.

But unlike those kidnappings, the Niger State incident ended relatively quickly. Gov. Abubakar Sani Bello sent a local vigilante group into the forests on a search-and-rescue mission. The kidnappers released most of the captives in 10 days.

In parts of Nigeria, attacks by armed bandits and extremists have become so common that civilians have established vigilante groups to augment overmatched police and Soldiers.

These vigilantes face no less danger than do their official counterparts. In March 2021, criminal gangs killed two dozen vigilante guards and a Soldier in central Nigeria. Dozens of bandits riding motorcycles opened fire on the vigilantes in an ambush in Mariga Local Government Area in Niger State. The vigilantes were tracking bandits who had attacked an area military post.

The original goal of Boko Haram, formed in 2002, was to inflict a fanatical form of “pure” Islam on northern Nigeria with an ultimate vision of overthrowing the Nigerian government. The group’s current insurgency began in 2009, and since then it has killed more than 36,000 people and forced an estimated 2.3 million people from their homes.

Violence linked to Boko Haram and its offshoot, Islamic State West Africa Province, has doubled since 2015, when the government launched a major offensive dislodging the groups, according to the Africa Center for Strategic Studies. Since then, the center notes, the two groups have focused on lightly populated areas of Borno State, including the rugged Sambisa Forest that borders Cameroon’s northwest mountains and the firki (“black cotton”) swamps south and southwest of Lake Chad.

But the extremist groups are not the only problem. Criminal gangs roam northwest and central Nigeria, stealing cattle and kidnapping people for ransom. They kill, loot and maim. They torch houses. They have no ideology, and their motives are purely financial. There is a growing concern that they have been infiltrated by extremists from the north.

A PROBLEM OF SCALE

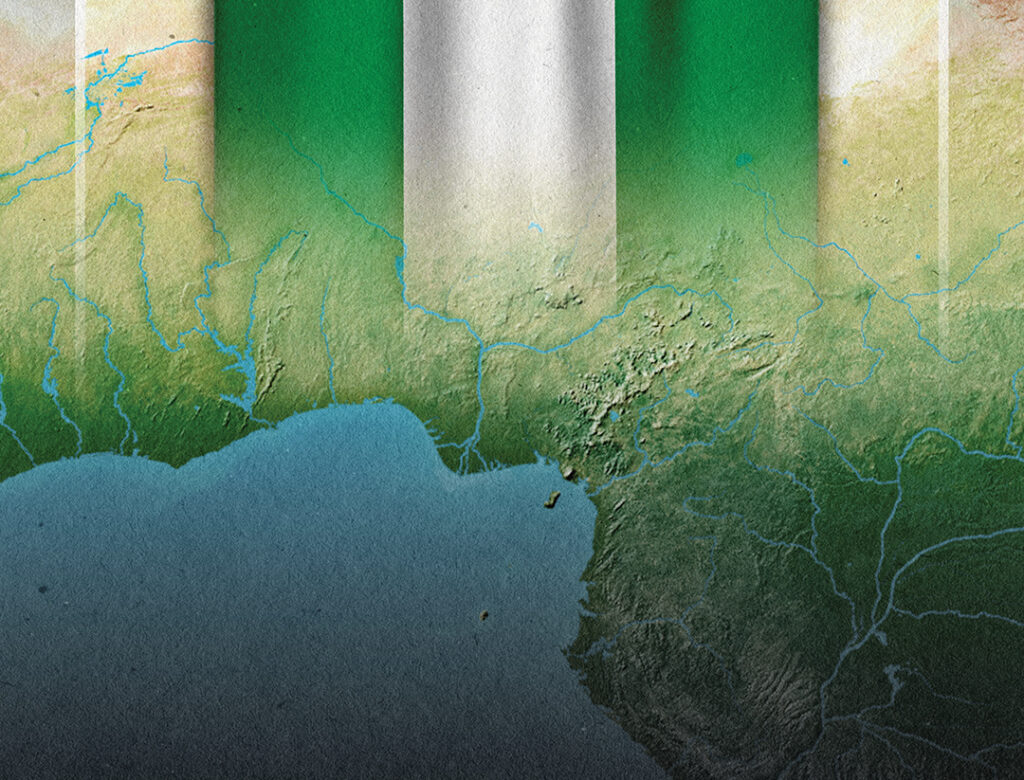

Police and Soldiers have been unable to halt extremism, banditry and intercommunal violence. But observers say this is not entirely their fault. Nigeria has a problem of scale. Although it is only Africa’s 14th-largest country by area, it is the continent’s most-populous country and has the biggest economy. Its 36 states include Christian majorities in the south and Muslim majorities in the north. It is one of the most culturally diverse countries in the world, with more than 500 languages and 300 ethnic groups. And the terrain can be challenging, particularly during the rainy season.

There’s also the problem of numbers. The ratio of police to civilians is well below United Nations recommendations. The New Humanitarian news service also notes “the lack of equipment, poor training, and low morale of the average officer” in Nigerian police agencies.

The federal government has turned to its Armed Forces for help, but they also are understaffed and overwhelmed by the conflict in the northeast. And the Soldiers are not trained for a policing role. “That means they are all too frequently shooting to kill, and with almost complete impunity,” The New Humanitarian reported.

These conditions have led to vigilantes — citizens who take the law into their own hands. In most parts of the world, vigilantes are a threat to security. In parts of Nigeria, they are becoming a state-sanctioned necessity.

on March 1, 2021. The gunmen overwhelmed police and vigilantes. THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

GROWING PROBLEM

The problem is getting worse. The rate of kidnappings across Nigeria increased by 169% from the beginning of 2019 to the end of 2020, the United States Institute of Peace reported.

In a report posted on its website titled, “Six Alternative Ways to Measure Peace in Nigeria,” the institute concluded that the increasing level of insecurity in the country could be attributed to poor performance by its security agencies. That, in turn, has led Nigerians to resort to taking the law into their own hands by establishing vigilante groups.

“When measured by the death toll, Nigeria seems beset by violence,” the report said. “By some accounts, the COVID-19 pandemic has made experiences of violence even more common.”

The institute’s report used research from four Nigerian states. The report noted that citizens asking for help from police reported disappointing results, with 64% of respondents saying that the experience was “difficult” or “very difficult.”

“There is strong support for vigilante groups,” the report said. “While many observers have concerns about the accountability and discipline of these vigilantes, and there is limited oversight over their activities, Nigerians who participated in this research express strong support for vigilante groups. More than eight in 10 respondents in all the surveyed states agreed that ‘vigilantes make a positive contribution to security in Nigeria.’”

The institute said that less than 10% of its respondents felt that vigilantes have a negative impact on Nigerian security. Although the institute’s surveys involved only four of the country’s 36 states, the results generally can be construed as consistent with the rest of the nation. The Lagos-based SBM Intelligence security company reported that in April 2021, 590 Nigerians were killed in violent attacks across the country, with just five states spared.

NATIONAL POLICY

The position of the Nigerian government continues to be that, given sufficient resources, its police and Soldiers can protect its citizens without auxiliary forces. But that is not the view of many of the country’s 36 governors, who have learned to look the other way at the formation of vigilante groups, and in many cases, actually endorsed them.

One such group is the Civilian Joint Task Force, formed in Borno State in 2013. It began as a group of local hunters who wanted to protect their communities, but as the news organization The Conversation noted, the task force soon became integrated into the government’s official counterinsurgency effort. In 2016, experts told The Economist magazine that the task force had more than 26,000 members in Borno and Yoko states, with 1,800 getting a salary of $50 per month.

Over the years, the task force has used its deep knowledge of local communities and terrain to identify members of Boko Haram and limit their attacks. In recent years, the task force has provided security at camps for displaced persons. But like many Nigerian vigilante groups, members of the force also have been accused of abuses, including murders. In 2017, the United Nations had to pressure the task force into ending its practice of recruiting children.

Some vigilante groups have origins as self-appointed police who gain legitimacy through government endorsements. The Bakassi Boys got their start patrolling a market in the city of Aba in Abia State and now operate in the nation’s southeast. The state government renamed them the Abia State Vigilante Service in 2000, giving them money and equipment. That same year, the Anambra State governor invited the Bakassi Boys to deal with increased crime there. The State House of Assembly passed a law to legitimize the group as the Anambra Vigilante Services. Imo State followed suit.

The Bakassi Boys have not been universally well received. In 2018, the Nigerian Supreme Court upheld the death penalty imposed on three members of the Bakassi Boys for two murders committed in 2006. Nigeria’s Punch Newspapers reported that Justice Amina Augie, who delivered the judgment of the Supreme Court said, “The Bakassi Boys are nothing but outlaws.” She said they were “lawless persons operating outside the law, who desecrate the laws of the land in their unlawful and misguided quest to dispense justice by killing alleged criminals.”

NO ‘TYPICAL’ GROUPS

There is no “typical” vigilante group in Nigeria. Some are funded and equipped by local governments. Some groups number in the hundreds, even thousands, of volunteers. And some are spur-of-the-moment revenge seekers, called to action by local leaders to avenge an attack.

Nigeria’s security problems are West Africa’s and the Sahel’s problems. With more than 200 million people, Nigeria has tremendous influence over the entire region. As Foreign Affairs magazine has noted, “When Nigeria slips into recession, the rest of the region’s economies typically stop growing.”

In pointing out the failings of regional security groups, Foreign Affairs noted that “they also have the potential to generate more flexible and nuanced responses to local security challenges, especially if the federal government can start to address some of the economic drivers of instability.”

Others also have defended the groups, saying they are a logical reaction to a problem.

“We run a federation; we have three tiers of government: federal, state and local governments,” said Edo State Gov. Godwin Obaseki. “Why should security be exclusive to the federal level? What happened to the other two? Until we address that structural imbalance, we are not going to be able to deal with security at its core.”

Some regions have established regulations to monitor the vigilante groups. As The Conversation website has reported, official regulation has not completely eradicated abuses, but it appears to be more useful than banning the groups.

“Moreover, the effectiveness of vigilantism in combating crime cannot be contested,” The Conversation noted. “With enhanced training and accountability mechanisms, these groups could provide an important component of community policing.”

Critics of the vigilante groups say the nationwide lack of security can be addressed only with truly strong police and military systems. Anything else represents a national failure, they say.

Shehu Sani, a senator for the opposition People’s Democratic Party in Kaduna, said in May 2021 that Nigeria needed to restructure and better fund its police.

“The government has just failed to live up to its responsibilities and expectations,” he said, as reported by The Guardian. “Corrupt security officers feeding on the defence budget must be dealt with and the welfare of troops must be upgraded. The military and the police must be better armed to match the bandits and terrorists.”

Nigeria Is a ‘Soup’ of Security Responses

Dr. Mark Duerksen is a research associate at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies. His research focuses on Nigeria’s security landscapes and Africa’s unparalleled urbanization, along with the security challenges and opportunities that cities present. His projects at the center include tracking security-related news and creating analytic infographics. Africa Defense Forum (ADF) interviewed Duerksen via email. His remarks have been edited to fit this format.

ADF: Are Nigeria’s mercenary groups actually working? It seems that many of them become as bad as the organizations they are set up to combat. For instance, a federal judge in Nigeria said the Bakassi Boys are “nothing more than outlaws.”

Duerksen: It’s a complicated question, and it’s not always clear whether Nigeria’s regional and local nonstate security outfits are working, and it may be too early to tell in some cases. I think it’s important to distinguish between:

- Private security organizations that are usually contracted by private interests.

- Local militias and vigilante groups that are set up to defend local property and communities, and sometimes are condoned, equipped and trained by local governments.

- Regional security outfits that are set up or officially sanctioned by state governments, even if their constitutionality is disputed.

All of these forces sometimes overlap geographically and operate in Nigeria in addition to the country’s myriad military forces, numerous divisions of federal police, as well as other security forces such as the State Security Service. So, there’s really a “soup” of security responses in Nigeria of all these different groups ostensibly trying to make the country safer from the diversity of armed groups operating in the country.

In the case of turning to vigilante groups or new regional forces to fill the security vacuum, these groups often follow a similar pattern of eventually engaging in the kinds of criminal behavior and abuses that they were tasked with preventing. This is the case with the self-defense militias in North West — they were initially established by local farmers to protect their interests against well-armed herder-aligned militias, but over time they have engaged in torture, atrocities and have even become feeders for the notorious criminal gangs that operate in the region.

Outcomes like this, which are also seen in the case of the Bakassi Boys, are the result of these forces having less oversight and receiving even less training than official security forces.

ADF: Are there some exceptions to this?

Duerksen: Yes, there are absolutely communities that have benefited from establishing local outfits that patrol and keep a lookout, but this is often dependent on the dedication and oversight of individual local leaders rather than institutional checks and accountability. So it can be difficult to replicate any of these successes to make a significant dent in Nigeria’s systemic insecurity.

Ultimately, these “alternative” security solutions are unlikely to deliver sustainable results unless they can be integrated into official institutions that will monitor, train and hold them accountable. In the meantime, documented violent events by armed groups in Nigeria have increased significantly over the past five years, from under 700 events per year to over 2,000 per year. Every year a significant number of events involving violence against civilians are attributed to Nigeria’s security forces and to militias that were originally set up to increase security locally.

ADF: Despite all the publicity at their startups, the mercenary groups Amotekun and Shege-Ka-Fasa do not appear to be accomplishing much of anything.

Duerksen: It is unclear what either of these groups is accomplishing beyond generating controversies over their legality. Meanwhile, the rash of kidnappings for ransom in the north and the security sector violence against civilians in the South West continues. Additionally, regionalizing security may create unintended problems if these forces operate with ethnic bias or under a banner of ethnic nationalism. Eventually, if these regional forces are not professionalized, they may aggravate regional divisions, which have long plagued Nigeria. The last thing Nigeria needs is a buildup of regionally loyal and ethnically organized security forces, especially when they’re connected to separatist groups like the Eastern Security Network, which was recently established by the leaders of the Indigenous People of Biafra’s militant movement.

ADF: It seems likely that the only long-term solution to the country’s security problems will be a commitment to hiring and training more police and, possibly, more Soldiers, and abolishing the practice of mercenaries. Is that a flawed theory?

Duerksen: The problem is that more often than not, setting up new forces or taking matters into one’s own hands via vigilante groups or newly sanctioned security outfits is the path taken in Nigeria instead of politicians and civil servants engaging in the challenging and long-term work of security sector reform, professionalization and trust building. Sensible reforms have been proposed by expert panels, but these haven’t ever been fully implemented, and, over the years, the police units in need of reform have essentially been rebranded under new names and reconstituted without addressing their underlying issues. There are some proposals and optimism that more effective units could be established through community policing initiatives. So, there is room for innovation and new ideas so long as they are created to tackle the problems identified by review processes and their results are assessed over time. This could also be done through the creation of public safety forces, which would help Nigeria look toward more comprehensive and integrated security solutions.

In short, Nigeria’s security architecture can be overly complicated and nebulous and often lacks the transparency and accountability needed for effective reform — something that needs to be addressed in the process of developing a multidimensional national security strategy. A serious reform and training effort of the country’s military and police with a focus on integrated security responses (involving government services, social development and justice initiatives) is Nigeria’s best bet for tackling the diversity of security threats the country faces.