ADF STAFF

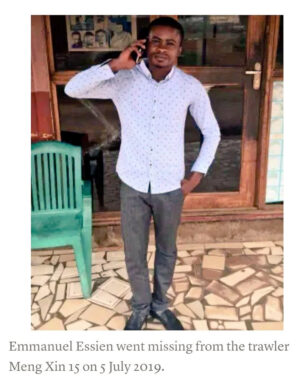

Emmanuel Essien, a 28-year-old Ghanaian fisheries observer, was proud of his work, which included reporting illegal fishing tactics aboard foreign fishing trawlers.

Emmanuel Essien, a 28-year-old Ghanaian fisheries observer, was proud of his work, which included reporting illegal fishing tactics aboard foreign fishing trawlers.

His diligence may have cost him his life.

Essien was on board the Chinese trawler Meng Xin 15 when he captured video of the crew engaging in saiko, the illegal transfer of fish from a trawler to a large canoe. Two weeks later, on July 5, 2019, he went missing while working on the same vessel.

His report on the video he captured included this sentence: “I humbly plead with the police to investigate further,” The Guardian reported.

After three years, the Marine Police Division of the Ghana Police Service has no information on Essien’s whereabouts or what led to his disappearance. Initial police reports said there were no signs of a crime. Essien’s evidence could have meant a $1 million fine for the vessel’s captain, according to The Guardian.

Under Ghanaian law, authorities must have a body in order to declare someone dead — or prosecute someone for their disappearance, Ghanaian news website myjoyonline.com reported.

Essien’s family, including a young daughter and son, are struggling to make sense of the disappearance. Essien’s brother, James Essien, said his niece, 6 at the time of her father’s disappearance, constantly asked where her father was. The family lives in Accra.

“I don’t believe the government and the authorities valued the work my brother was doing,” James Essien told The Guardian in 2019. “If they did, they would attach some seriousness and urgency to the investigation. We know nothing. We don’t understand how it can take so long.”

The Guardian interviewed two fishermen in nearby Tema in the wake of Essien’s disappearance. The fishermen spoke under condition of anonymity. They said some fisheries observers were beaten by Chinese crews and both saw observers accept bribes.

“The observers are there to report bad behavior,” one fisherman said. “It is like being a spy. When we heard about an observer going missing, we were very unhappy. It is very dangerous.”

They agreed that it would be difficult for an observer to fall overboard.

“It would be very hard,” one said. “He is not working on deck like the fishermen.”

James Essien said his brother was on the verge of quitting his job because he was no longer comfortable.

“I don’t believe my brother threw himself off the boat into the sea,” he told The Guardian. “There is no way he would do that. I suspect there was a coordinated attempt to take him off. He was going to write up a report. Perhaps there was a disagreement. Perhaps the Chinese didn’t like it.”

Observers typically share space on the vessels with the Chinese captain and crew, away from other workers. Kobina Yankson, a professor with the department of fisheries and aquatic science at Ghana’s University of Cape Coast, thought this was a terrible practice.

“How do you put a solitary young man on a fishing vessel with Chinese crew?” Yankson, now deceased, said in a 2020 report by the Fisheries Committee for the West Central Gulf of Guinea. “And he is to report illegalities and take photographs. Do you think the crew will allow him to do that? I don’t know who gave this advice.”

A source at Ghana’s fisheries commission told The Guardian observers are warned of “hostility” on foreign vessels and that they are threatened “most of the time” when they film illegal activities.

Foreign ownership of trawlers is illegal in Ghana, but Chinese trawlers use Ghanaian front companies to allow them to fish. According to Environmental Justice Foundation, Chinese companies finance about 90% of industrial trawlers in Ghana.

The Meng Xin 15 belongs to Dalian Meng Xin Ocean Fisheries, a Chinese state-owned enterprise, China Dialogue Ocean reported.

Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing has been rife in Ghana for decades. It has devastated fish stocks and threatened the livelihoods of 2.7 million Ghanaians.

“The fishing trawlers are our biggest headache now,” Edward Kotei, a fisherman in Jamestown, said in a report by the Fisheries Committee for the West Central Gulf of Guinea. “They have flooded our shores and flouting the laws. They come all the way into our territories to fish. The trawlers come all the way down shore to catch the fish and dump a large chunk of the small ones back in the water and then move from our territories and go elsewhere.”