Mediation strategies can help end conflict and lay a foundation for lasting peace

Nations trying to prevent or defuse conflict are experimenting with all types of peacekeeping strategies. They build coalitions of nations to intervene, enact sanctions, use high-tech devices such as drones for surveillance and train elite rapid-reaction units. But too often one aspect of conflict resolution is ignored or used only as a last resort: mediation.

History shows that mediation –– resolving disputes through dialogue –– is a cost-effective and bloodless way to bring about a stable peace. But it is not as simple as gathering warring parties around a negotiating table and letting them talk things out. Mediation, like kinetic operations, has its own tactics, techniques and procedures that have proved, over the years, to increase the likelihood of success.

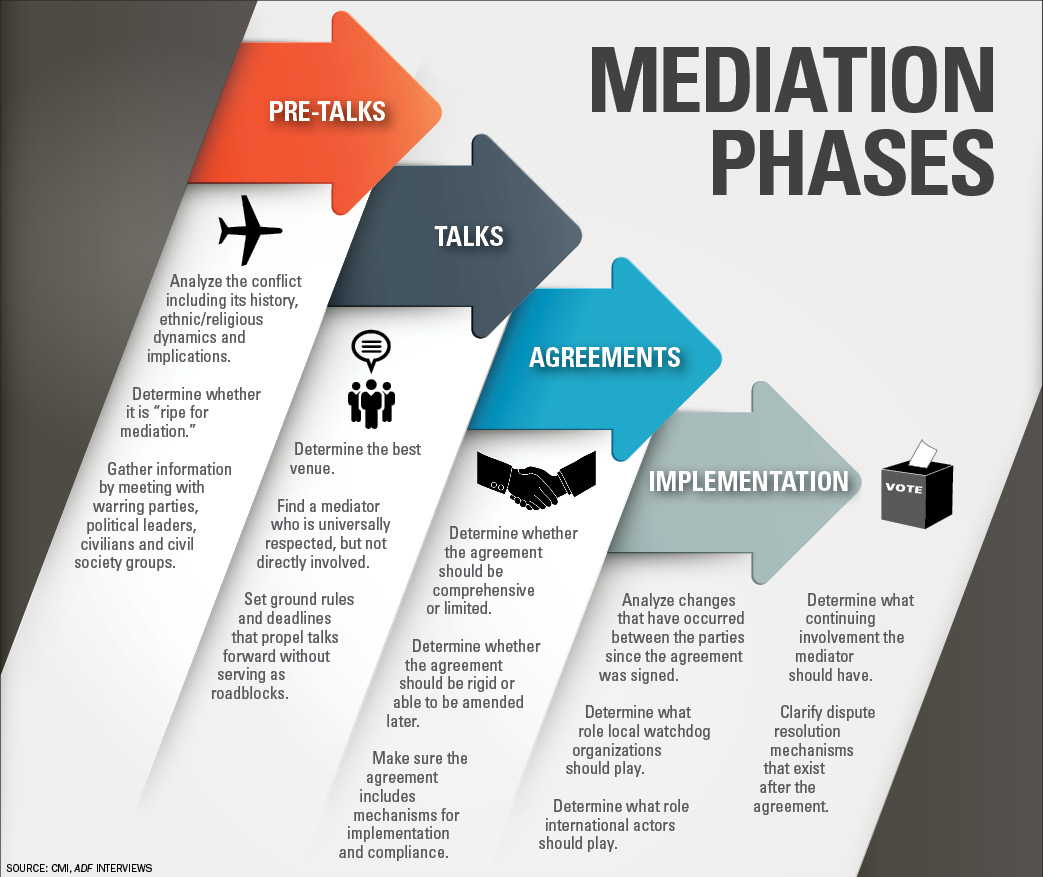

The Helsinki, Finland-based Crisis Management Initiative (CMI) listed the four phases of mediation and some lessons learned in a 2013 report, and CMI experts relayed some of those lessons in interviews with ADF.

The Pre-Talks Phase

The most important assessment to make before beginning mediation is whether the conflict is “ripe” for resolution. Mediators must ask: Are warring parties ready to set aside arms and pursue peace in good faith? Or are they still fixated on the deadly and wasteful idea of winning the war?

Former U.N. Assistant Secretary-General for Political Affairs Alvaro de Soto said ripeness occurs when combatants determine that “the cost of coming to an agreement has become less than the cost of pursuing the conflict.”

Former U.N. Assistant Secretary-General for Political Affairs Alvaro de Soto said ripeness occurs when combatants determine that “the cost of coming to an agreement has become less than the cost of pursuing the conflict.”

Waiting for the right time, though, can be gut-wrenching as mediators watch a war drag on pointlessly. Col. Mbaye Faye, a retired Senegalese Army officer and a former member of the U.N. Department of Political Affairs’ Standby Team of Mediation Experts, cautioned that a premature mediation can actually make things worse and even reignite conflict. “If they are not convinced of the need to leave something in order to gain, the give-and-take process is not in their minds,” he told ADF. “It will be useless to get into such a process.”

Mediation was premature during the civil war in Sierra Leone. In 1996, the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) and the Sierra Leone People’s Party signed the Abidjan Peace Accord. But fighting quickly resumed. Observers now believe the conflict was not ready for mediation because the RUF still was convinced it could win militarily.

Even if warring parties are ready to talk, mediators must do advance work to understand their background and motivation. Faye said the goal is to find the root cause of the conflict. He recommends that mediators do research that digs deeper than the publicly available material because published accounts can be inaccurate or slanted. Mediation teams should meet informally with faction leaders for tea, coffee or dinner, he said.

Faye said civilians and civil society groups also should have their say. It can be beneficial to set up what some West African countries call a “palaver hut,” so people from the community can come by to discuss issues informally without fear of retribution.

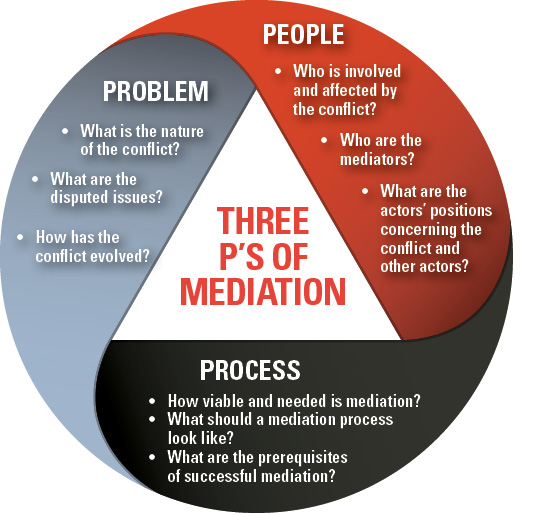

CMI separates the key elements of pre-talks into three P’s:

Problem: A mediator should understand the full context of the dispute, including the issues being contested; the history; and its national, religious or ethnic implications.

People: Who are the warring parties? How powerful are they? Who do they represent? What are their motivations?

Process: What are the ground rules for talks? Has the mediator’s role been explained and accepted by all parties?

The Talks Phase

Once started, peace talks do not follow a consistent pattern, nor do they have a reliable timeline. Some, like the talks to end the civil war in Burundi, can last more than a decade. Others, like the 2005 talks with Aceh rebels in Indonesia, proceed from negotiation to implementation in just months. The forum is another variable. Sometimes talks are held around a table, and sometimes they take the form of “proximity talks,” in which a trusted third party shuttles back and forth between warring sides.

Experts tend to agree that the best venue for talks is outside the conflict zone and often outside the country itself. This is key for the security of those involved, but it also lets the parties interact in an open, relaxed environment.

The late Margaret Vogt, a Nigerian native and former U.N. representative in the Central African Republic, believed it was important to bring parties back to the conflict zone periodically for a “reality check.” “They need to first of all bring the results of whatever they are agreeing [to] back to the people,” she told CMI. “Secondly, they need to assure that whatever they are discussing reflects the priorities and needs of the people on the ground.”

Deadlines: Deadlines and progress markers are vital. Otherwise, mediation might drag out over years as combatants squabble over minute details. However, CMI experts caution against setting rigid or aggressive deadlines, which can result in hasty agreements that are more likely to be broken.

Faye calls rigid deadlines “deathlines” because they can kill the process. “We should have deadlines for the purpose of planning and organizing, but still there must be flexibility,” Faye told ADF. “Because these are living processes with living people, and you have to adjust to the reality. Reality is the overriding principle.”

In some cases a firm deadline acknowledged by both sides spurs the parties to action. The Good Friday Agreement of 1998 that led to peace in Northern Ireland was one of those instances. Talks went hours past the deadline, but both sides finally signed the historic pact.

All Parties Present: People participating in mediation aren’t a group one might invite to a social gathering. Rebel or militia leaders may be morally abhorrent, but they still must have a seat at the table.

“If you want peace, you have to talk to the combatants,” Bishop George Biguzzi, a mediator in Sierra Leone, told CMI. “Peace with your friends, you have already.”

“If you want peace, you have to talk to the combatants,” Bishop George Biguzzi, a mediator in Sierra Leone, told CMI. “Peace with your friends, you have already.”

Terrorist groups or ideological extremist groups present a more nettlesome problem. Some experts think they never should be included. Others contend inclusion is the only way to show them that dialogue works better than attacks. It is also vital that civil society groups have a voice so civilians do not view mediation as a reward given only to armed combatants.

Faye cautions against widening talks too extensively. He recalled participating in a recent mediation that included more than 100 representatives speaking for factions of the dominant political party, different ethnic groups, minor political parties and civil society groups.

“Too much inclusivity can hamper a process,” he said. “The question becomes, ‘What do you want to do? When? And with who?’ If you’re aiming to first and foremost resolve the problem of war, you must first deal with the warring factions.”

One Mediator: History shows that multiple mediators mean parties will look for the best deal and seek to play one against the other. An example was the peace talks in Darfur in the late 2000s. The African Union and the U.N. each had its own mediators, which “caused confusion as to who was the legitimate mediator and actually leading the process,” CMI wrote. “Both organizations held separate meetings, wrote their own reports, and had different support teams, which only intensified the confusion on the ground.”

A better example was set after the Kenyan election violence in 2008. There, former U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan established himself as the sole mediator and firmly guided both parties in the disputed presidential election toward a coalition government.

A Good-Faith Mediator: An effective mediator must command instant respect but not be seen as having a stake in the success of any of the parties. To that end, there are advantages and disadvantages to having a mediator with direct ties to the conflict area. The advantages are that he knows the culture, the players and has an inherent interest in a positive resolution. The disadvantage is that local ties can override the mediator’s impartiality in fact or in perception.

For that reason, many successful mediation efforts in Africa have been led by men with continentwide respect but no local ties to a conflict. Prominent mediators of recent decades include former Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere, former South African President Nelson Mandela and Annan.

Itonde Kakoma, the head of CMI’s Sub-Saharan Africa program, said mediators can take an active or passive approach, depending on the situation. He pointed to the “facilitation” effort in Arusha, Tanzania, in October 2014 with the leaders of South Sudan’s ruling party. There, the chief facilitator, Tanzania’s former Minister of Defense Abdulrahman Kinana, told all parties that there was no “magic bullet” to the problems and he was primarily there to “listen with humility” and not to impose solutions.

“He held long, patient listening sessions with all of the delegations independently before saying a word — before interpreting his understanding of the crisis or what needed to be done,” Kakoma told ADF. Later, he “assembled them together as a full plenary and said, ‘This is what I heard you say. Is it accurate? Have I heard you correctly? Correct me where I’m wrong.’ ”

The result of the Arusha talks was a document in which party leaders frankly admitted responsibility for the troubles dividing South Sudan.

Depending on the crisis, a more activist stance may be required. Nobel Peace Prize laureate, founder of CMI, and former Finnish President Martti Ahtisaari does not care for the term “neutral” to describe a mediator. Instead, he prefers “honest broker.” “If you say you are neutral, you are saying that you will come to the negotiations to listen to the parties and their views. That kind of a process can take many years, if not decades,” he told CMI. “It is important that the negotiating parties know who I am, what I stand for, and where I draw red lines. This way I can honestly and openly work with each party toward finding a solution.”

Agreement Phase

Although a peace agreement is the goal of any mediation, it must have the right scope, inclusivity and flexibility. It also is important that the agreement has enforcement mechanisms to ensure that it is implemented and followed universally.

Most think simplicity is an asset since it is easier to agree on a shorter list of topics. “Once you get those key issues fixed, then the other issues do not necessarily have to be addressed in the agreement itself,” Solomon Berewa, former vice president of Sierra Leone, told CMI. He participated in peace talks to end his country’s civil war. “If the parties trust each other, they can solve disputes after signing the agreement.”

If an agreement is too rigid and does not allow for future amendments, it risks falling apart. However, the core elements of the agreement, what CMI calls the “soul,” should not change. When multiple issues are fueling a conflict, such as the distribution of resources, ethnic or religious representation in the government/military, or the demarcation of a border, the issues can’t be avoided in the agreement. Less essential issues, such as the dates of elections, can be postponed without risking the entire agreement collapsing.

It is typically best to start with simple topics and progress to more difficult ones. That way, like a ball rolling downhill, the process gains momentum, and confidence is built between the parties.

Implementation Phase

The mediator and international community play an important role in the months and years after an agreement is signed. Unlike the talks phase, in which it is good to have one person serve as mediator, the guarantors of an agreement can be a large and diverse group. The Comprehensive Peace Agreement signed between Sudan and South Sudan in 2005 included an Assessment and Evaluation Commission, which consisted of parties such as the Intergovernmental Authority on Development, the U.N., the AU, the European Union, the Arab League, and various nations including Norway, the United Kingdom and the United States.

The diversity of observers and guarantors helped show that the world was watching and made sure that certain agreed-upon terms, including the vote for South Sudanese independence, were honored.

CMI found that it also is important to empower local actors to serve as watchdogs to make sure the agreement is being honored.

Faye said that, in his experience, the most important elements of implementation are monitoring and verification. Parties need to know that the progress toward agreed-upon objectives is being tracked, not only in terms of cease-fires and a lack of fighting, but also politically in matters such as building a coalition government and preparing for an election.

“The fact that you’ve signed an agreement doesn’t mean that all of a sudden you’ve become good friends or you trust each other,” Faye said. “We say the first victim of conflict is trust. Trust in yourself, trust in the others, trust in any external organization. Recovery of trust is a process, and it requires monitoring and verification.”

The Case Study of Burundi

Although the genocide in Rwanda is far more well-known, many of the same volatile elements existed in neighboring Burundi in the early 1990s. In October 1993, the country’s first democratically elected president, who was also the country’s first ethnically Hutu president, was assassinated, and the nation appeared ready to descend into chaos.

“The risk of genocide in Burundi was almost as severe as it was in Rwanda, where it materialized. Incitement to genocide was going on every day,” wrote Ambassador Adonia Ayebare, a Ugandan meditator who worked on peace initiatives in Burundi. “What made the difference in successfully preventing genocide in Burundi was the substantial and sustained engagement of the international community, which sent the right message to the right people at the right time.”

It is impossible to call the mediation in Burundi a complete success. Violence persisted off and on for more than 15 years, and a civil war led to the deaths of 300,000 people in the tiny nation. However, experts believe that the sustained focus of African leaders and the wider international community avoided the worst outcome.

The mediation initially was led by the venerable former president of Tanzania, Julius Nyerere. He succeeded in bringing 19 delegates representing various parties to Arusha, Tanzania, in 1998. The talks were productive, but the fact that certain armed groups were excluded meant fighting continued.

In 2000, after Nyerere’s death, former South African President Nelson Mandela took over the mediation. He brokered the Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement signed in August 2000. The agreement laid out a power-sharing arrangement among warring factions with guaranteed representation of the two largest ethnic groups in the security forces and the government.

In 2002, Jacob Zuma, then the deputy president of South Africa, took over the role as facilitator. One of the key differences in Zuma’s approach, wrote Ayebare, was to closely examine the diverse armed groups inside and outside Burundi that still were fighting. He launched a technical committee of intelligence officials from neighboring countries to report to him about the motivations of the armed groups. He also brought the largest armed group, the Council for the Defense of Democracy, to the talks. In December 2002, he successfully got all parties to sign a comprehensive cease-fire.

This cease-fire created the space for the U.N. to deploy a mission to Burundi, replacing the AU’s African Mission in Burundi. The peacekeepers helped create an environment in which national elections could be held. The last remaining armed group, Palipehutu-FNL, came to the table for peace negotiations in 2006.

FOUR LESSONS from Burundi:

Retired Senegalese Army Col. Mbaye Faye spent 10 years working for the U.N. in Burundi, holding the position of director of security sector reform and small arms/civilian disarmament. He also oversaw the signing of several cease-fires. In a conversation with ADF, Faye outlined lessons from the Burundi mediation:

Negotiate with those who are willing: Fighting did not end until the final group, the Palipehutu-FNL, came to the peace process in 2006. However, Faye said, that does not mean mediation should wait until all armed groups are ready to negotiate.

“All those who were ready for peace were taken on board,” Faye said. “Meanwhile, we continued to engage those who were not on board. If you wanted to wait until everybody was ready to come on board, it would cost even more lives and even more time.”

Representation: In a novel move, the Arusha Accords dictated that, in the new Burundi government, 60 percent of positions would go to Hutus and 40 percent to Tutsis. This quota system showed both sides that working together would be essential in the future, and there would not be a “winner-take-all” government.

“It gave hope to the minorities,” Faye said. “It gave hope to the minorities,” Faye said. “It reassured them that they are not losing power forever, and they are not at risk of what has happened in terms of a massacre that occurred in neighboring countries.”

Verification of the process: The process in Burundi included a National Peacebuilding Strategy, which had a section dedicated to poverty reduction. Progress was assessed every four months, and a report was sent to the U.N. headquarters and monitored by 33 countries. Faye said these progress reports empowered civil society members to be watchdogs of the peace process.

Integrating combatants: The Arusha Accords called for even ethnic representation in the police and armed forces. They also called for the integration of rebel forces into the national military. Faye said a lesson he learned was the importance of “rank harmonization.” This meant that a commanding officer in the rebel movement should be integrated at the same level in the new national army, once he passes competency tests.

“We showed that the incoming military from the bush … could meet a number of requirements including international standards,” Faye said.

This strategy has proved effective, and integrated Burundian units including former rebel leaders have served to wide acclaim as peacekeepers in the African Union Mission in Somalia.