ADF STAFF

Ethiopia’s civil war in the northern region of Tigray has dragged on for more than six months.

What Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed initially called “a law enforcement operation” against the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) has devolved into lawless chaos. The United Nations human rights office says that all parties involved are accused of committing war crimes against civilians.

There is no end in sight, and the conflict has sparked violent border disputes within Ethiopia’s ethnically separate, semi-autonomous states and with neighboring countries.

When Abiy consolidated power in 2019 by dissolving the country’s ruling party, he promised to hold free and fair elections. He cast himself as a unity candidate with his newly formed Prosperity Party promising democratization, harmony, reconciliation and liberalization of the federally directed economy.

But Ethiopia, once a bastion of stability in the Horn of Africa, never has been so divided.

Abiy blames “identity-based politics and violence.”

“I regret to acknowledge that we have not yet won the battle against enemies within,” he said in a televised speech on March 25, 2021. “We must revisit our traditions, certify our friendship and renew our time-tested solidarity.”

“I regret to acknowledge that we have not yet won the battle against enemies within,” he said in a televised speech on March 25, 2021. “We must revisit our traditions, certify our friendship and renew our time-tested solidarity.”

Ethiopia is highly diverse, with more than 90 ethnic groups among its more than 112 million people. The most numerous are the Oromo, Amhara, Somali and Tigrayans, which, together, constitute about three-quarters of the population.

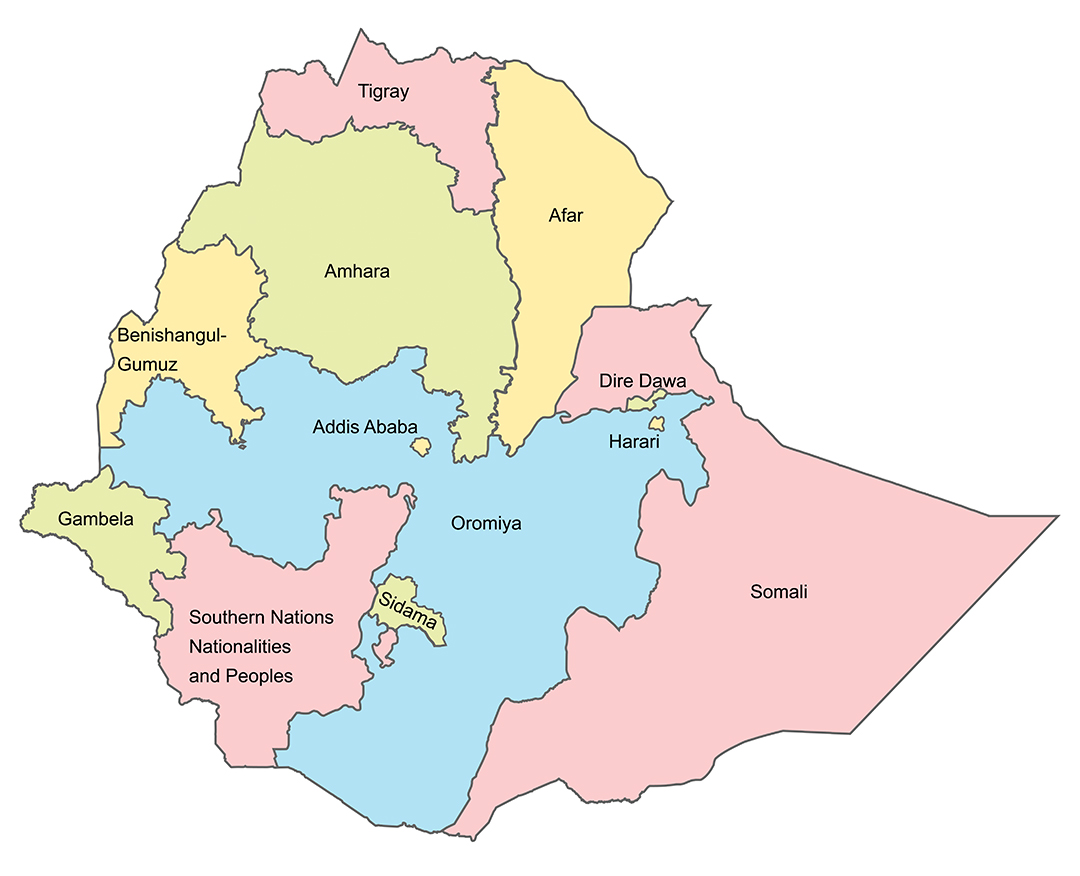

The country is facing a crisis with roots in its 1995 Constitution, which established ethnic federalism in hopes of creating equality. That system of governance, which divided the country into 10 ethnic regions, was implemented by a coalition government led by the TPLF after it helped liberate the country from the brutal Communist Derg regime in 1991.

Tigrayans held positions of power within Ethiopia’s government, military and economy for nearly three decades. During that time, resentment and ethnic divisions festered.

Now, Tigray is the epicenter of widespread ethnic and internal conflict that some fear could tear apart Africa’s second-most-populous country.

Federal forces launched a military operation against the northern region last November. This occurred after TPLF administrators defied the central government by holding elections, and Tigray forces attacked a military base.

More than six months later, thousands have been killed, and more than 1.7 million have fled to nearby regions and neighboring countries.

William Davison, an Ethiopia analyst with the Belgium-based International Crisis Group think tank, sees Tigray as the most dramatic example of ethnic and regional tensions that have surfaced across the country.

“With the conflict in Tigray set to continue, and many people there supporting armed resistance and even secession, the pressing challenge for the prime minister is holding the country together rather than how to further unify it,” he told Reuters.

Ethnic disputes over power, land and resources have erupted into violence ahead of the twice-postponed national elections.

Civilians on both sides of the border between Amhara and Oromia have been attacked in recent months, as ethnic militias tied to regional political parties attempt to drive out other ethnicities.

Officials say 36.24 million Ethiopians have registered to vote in the elections, now scheduled for June 21. Not participating is the restive region of Tigray, where Abiy admitted his military faces a “difficult and tiresome” fight against the remnants of the TPLF.

“The junta which we had eliminated within three weeks has now turned itself into a guerrilla force, mingled with farmers and started moving from place to place,” he said in an April address to lawmakers.

Abiy anticipates a fight in the coming election as well. Security issues in several hot spots are expected to cause delays, as regional leaders and strongmen have worked to organize local voting blocs.

The election could serve as a referendum on ethnic federalism or on the Prosperity Party’s platform of unity in a fractured country where deeply repressed rivalries have been dramatically exposed.

“No doubt Ethiopia is at a crossroads now,” Kassahun Berhanu, a professor of political science at Addis Ababa University, told The Associated Press. “Ethnic federalism isn’t bad, but it must be streamlined in a way that it does not exclude the need for nationhood. Because these two are not mutually exclusive.

“Ethnic rights can’t be at the expense of essential common belonging.”