ADF STAFF

In The Gambia, rosewood is big business.

China merchants buy it — hundreds of thousands of metric tons over recent years — even though it’s illegal to harvest. Government officials are bribed to look the other way, loggers have told reporters. Senegalese and Gambian businessmen profit from it, as do some armed groups. The Movement of Democratic Forces of Casamance, a separatist organization that has been fighting for the independence of Senegal’s Casamance region since 1982, is financed in part through timber trafficking.

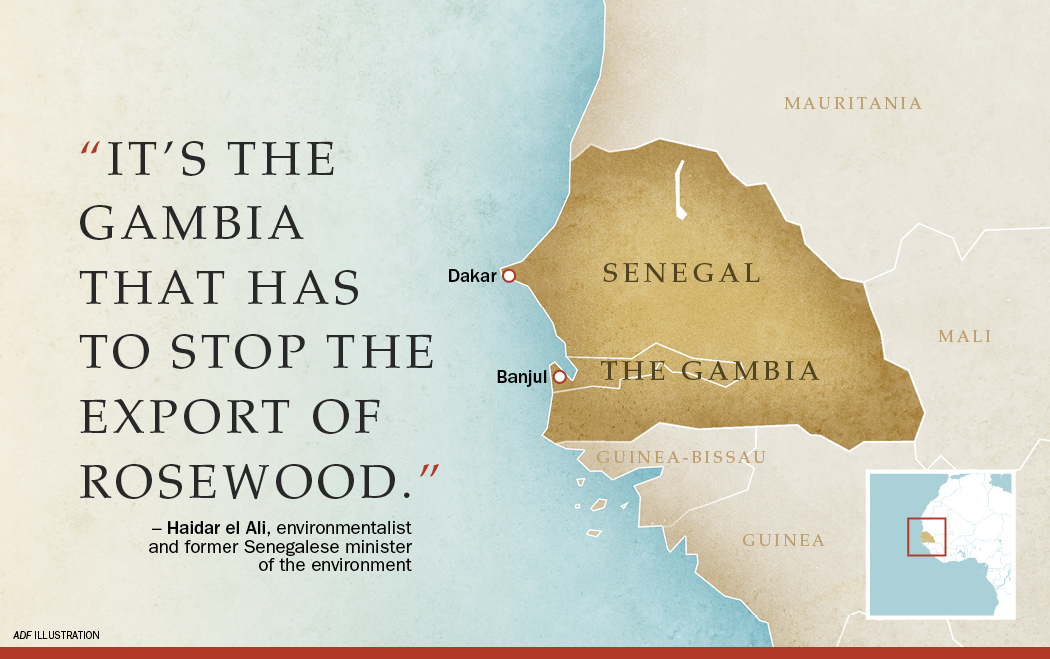

The Gambia, the smallest nation on mainland Africa, was stripped of most of its rosewood 10 years ago, and yet is consistently among the five largest global exporters of rosewood. The rosewood shipped out of The Gambia is being stolen from the Casamance region of neighboring Senegal. The African Union Development Agency has described Casamance as “the green lung and last forest stronghold of Senegal.”

Since 2017, the West African rosewood tree has had international protection. It was listed under Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, known as CITES. The treaty protects the living environment. The Gambian government, like Senegal, signed the convention, which allows a carefully regulated trade in rosewood so long as it is legal and sustainable.

The government of Senegal has fought against the illegal logging by revising its forest code. AFR100, the African Forest Landscape Restoration Initiative, reports that the revised code toughens penalties, strengthens forestry staff and uses the Senegalese Army to patrol for illegal loggers and smugglers.

The results of the enforcement show how illegal logging begins at the grassroots level: In a single week, officials in the Kolda region seized 119 carts, 43 horses, 98 donkeys, two chainsaws, two two-man saws, two axes and two motorcycles.

It’s a matter of supply and demand, and the demand mostly comes from China, where the dense, beautiful wood is used to make furniture. China has banned logging in its own natural forests and, for a time, got its rosewood from Malaysia and other countries in Southeast Asia. After depleting the rosewood in those countries, China began logging in Africa about 2010, according to Naomi Basik Treanor of the charity Forest Trends.

“The ‘Senegambia’ rosewood trade is on a par with conflict diamonds,” she told the BBC. “The nature of the conflict in Senegal and the very porous borders makes this trade very hard to contain.”

AGENCY INVESTIGATES

The BBC reported that China has imported more than 300,000 metric tons of West African rosewood from The Gambia since 2017. In June 2020, the nonprofit organization Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) released the results of its three-year investigation into the Senegal-Gambia-China rosewood trafficking. The report included these findings:

An estimated 1.6 million trees were illegally harvested in Senegal and smuggled into The Gambia between June 2012 and April 2020.

The rosewood traffic between Senegal and The Gambia largely has been controlled by the Movement of Democratic Forces of Casamance.

Traffickers themselves say that high-level Gambian officials have undermined the export ban put in place by the current Gambian administration.

Traffickers have used the politically powerful company Jagne Narr Procurement & Agency Services to bypass the ban.

Import-export figures do not add up. The Gambia reported $471 million less in exports of rosewood than its trading partners declared as imports between 2010 and 2018, the EIA said. In other words, China is buying even more of the wood than The Gambia acknowledges it is selling.

In its investigation of rosewood trafficking, the BBC found at least 12 depots containing rosewood and other timber along the 170-kilometer border between Senegal and The Gambia. They were all within Gambian territory. Despite it being illegal to harvest Senegal’s rosewood trees, the BBC observed such harvesting out in the open.

Officially, The Gambia’s government has banned the import of West African rosewood from Senegal. Under The Gambia’s Forestry Act of 2018, importation from another country is only legal if it goes through an official port of entry.

The EIA says the illegal trade could be stopped “almost instantly” if The Gambia established a zero-export quota for the lumber and gave notice to all convention parties, including China, which would have an obligation to stop shipments from coming into its ports.

“This could be a game-changer for The Gambia, as well as for the people and forests of Senegal, and would pave the way for a coordinated West African approach to save one of the most trafficked wild species in the world, and to combat desertification and climate change,” said Kidan Araya, Africa program coordinator for the EIA.

The EIA says that international organizations must pressure The Gambia to shut down its timber trafficking hubs, and other parties involved in the trafficking must take a stand.

Shipping company Compagnie Maritime d’Affrètement-Compagnie Générale Maritime (CMA CGM) has gotten the message. The company, the world’s fourth-largest shipper, says it has done its own investigations after published reports of illegal harvesting.

“There was probably some protected rosewood inside their shipments from The Gambia to China,” Guilhem Isaac Georges of CMA CGM told the BBC. He said the company has “decided to halt timber exports from the country until further notice.” The EIA believes the action is the first time a shipping company has banned the shipment of an entire classification of product.

The company also says it plans to create a global blacklist of shippers involved in the illegal trade of protected and endangered species.

But Haidar el Ali, an environmentalist and former Senegalese minister of the environment, said The Gambia remains the key player in stopping the trafficking.

“It’s The Gambia that has to stop the export of rosewood,” he told the BBC. “They make good speeches, good promises. They say, ‘We are going to stop,’ but in reality it is not true.”

Group Will Train 8,000 African Farmers

An organization determined to sustainably revitalize farmland will train more than 8,000 Sub-Saharan farmers in soil management, including some in Senegal, in a four-year program.

The Forest Gardens project is the work of Trees for the Future, an organization assisting communities around the world in growing trees through seed distribution. AFRIK21 reports that through the program, farmers can plant thousands of trees to protect their soil and restore nutrients. As a result, farmers will benefit from increased income and food security, just one year after the program starts.

The countries involved are Cameroon, Kenya, Senegal, Tanzania and Uganda.

Farmers will learn how to create forest gardens on their land. The goal is to improve soil health and biodiversity, grow diverse and nutrient-rich crops, increase incomes, and adapt to changes in the weather.

“Like most farmers around the world, these farmers have been practicing one-way agriculture for generations, using the intensification of monoculture farming,” Brandy Lellou of Trees for the Future told AFRIK21. “Through the Forest Garden approach, farmers are learning how to diversify crops, restore soils and maximize the full potential of their land.

“Farmers see their nutrition and income start to improve steadily in the first two years,” she said, “and by the end of the fourth year, a 0.4-hectare forest garden typically has about 2,500 trees.”

Trees for the Future says training is divided into five stages:

Identification: The organization identifies 200 farming families in need, selects training technicians and prepares materials for launch.

Protection: In the first and second years, farmers plant 2,500 fast-growing trees and bushes that create a protective and soil-stabilizing barrier.

Diversification: In the second and third years, farmers learn to diversify their field with vegetables and fruit trees to meet the family’s nutritional and selling needs.

Optimization: In the third and fourth years, farmers learn about advanced Forest Gardens management and conservation to optimize the long-term health and productivity of the land.

Graduation: In the fourth year, Trees for the Future implements a sustainability strategy with each farmer. A graduation ceremony celebrates the farmers’ program completion.