In response to the crisis of deforestation, Soldiers have planted millions of trees

Kenyan environmentalist Francis Muhoho says his country is risking an environmental crisis by cutting down too many trees.

“Kenya lost an average of over 200,000 hectares of forests per year between 2000 and 2014,” he said in March 2019, as reported by the Kenya News Agency. “This is both in government and private forests.”

Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta said that so far this century, East Africa has lost a total of 6 million hectares of forest, some of it containing plants and animals found nowhere else on Earth.

“Our forests are the lungs that keep this planet alive,” said Kenyatta, speaking at a 2019 environmental conference. “Deforestation and degradation of our environment ultimately undermine our efforts toward biodiversity conservation, climate change mitigation as well as adaptation.”

The Kenya Forest Service is doing its part to help, including distributing tree seedlings to farmers. And for years now, the forest service has had an unlikely ally — the Kenya Defence Forces (KDF).

The KDF acknowledged that the nature of the military’s mission has been part of the environmental problem. “Military operations — weapon tests and firing, digging of fire-trenches for protection from enemy direct fire and using of vegetation as camouflage for cover and concealment from enemy direct observation — wherever are undertaken, have affected the environment,” the KDF said. “Even though there are designated Military Training Areas on land, sea and air, population growth and urbanization are proving a challenge for the military.”

The KDF has been frank in assessing the negative role it has played in the environment. It said that farmers and herders have complained in the past about deaths caused by unexploded ordnance left behind after KDF training and exercises, as well as the deaths of animals after falling into abandoned foxholes that never were filled in. The KDF said it has attempted to address the damage its training has caused.

“Soldiers have taken it as duty and responsibility to care for and preserve the environment wherever they go,” the KDF said.

In 2003, it took the proactive step of forming the Environmental Soldier program, with the sole purpose of planting trees.

In an email to ADF, the KDF said “changing climatic patterns across the world are having impacts ranging from dwindling natural resources, impacts on health and safety of populations, to threats of extermination of whole nations, especially the small island nations facing threats from sea-level rise.”

KDF officials said, “The usual thinking and practice for most response strategies has been largely reactive and the impacts temporary.” The KDF determined that the environmental situation was compromising the accomplishment of its mission and decided it was “time to act in order to effectively protect and preserve the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the country.” Thus began the Environmental Soldier program. Its goals are:

- To reduce the overall carbon “boot-print” of the KDF.

- To start an ecological restoration program.

- To encourage efficiency and sustainability in the use of natural resources.

- To promote behaviors that improve the environment.

Kenyan officials say that one of the main reasons for focusing on planting trees was because of the relative ease of the task, which could be used to give early positive outcomes as well as long-term benefits. To make it work, the Soldiers had to form partnerships with other government institutions, communities, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and corporations. Among the first partners were the Kenya Ministry of Environment and Forestry; the United Nations Environment Programme; and Nobel Peace Prize winner Wangari Maathai, founder of the Green Belt Movement. The Green Belt Movement is a Nairobi-based NGO that focuses on environmental conservation, community development and capacity building. In 2007, the movement partnered with the KDF to plant 44,000 trees in the Kamae Forest to restore the region’s main water catchment and to prevent erosion.

A LARGER PURPOSE

With the support of the Ministry of Defence, the KDF established tree nurseries within some military units to ensure that there would be enough saplings for planting during Kenya’s two rainy seasons.

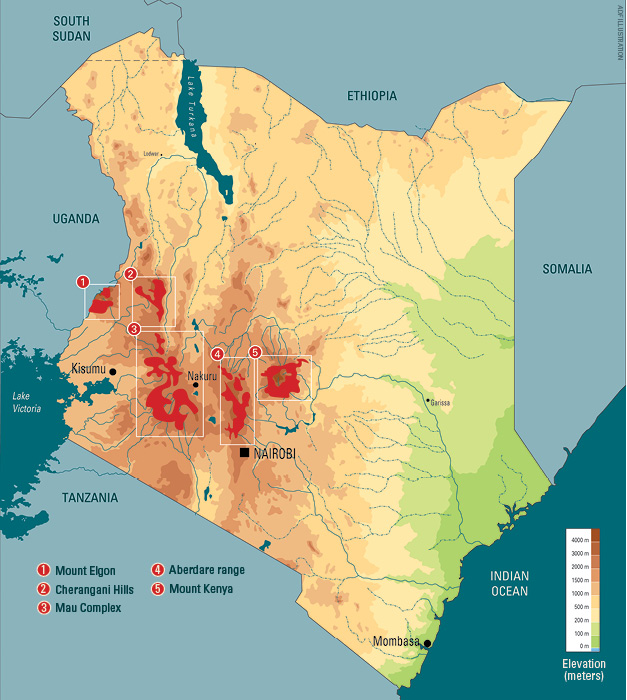

Initially, Soldiers focused on planting trees in the country’s five main mountain forests, also known as “water towers,” because they collect water from all but one of Kenya’s main rivers. The plantings have since been expanded to cover more than 50 forest areas and public lands throughout the country.

The KDF plantings follow a globally tested method developed by Japanese botanist Akira Miyawaki. It involves researching the trees that originally existed in a degraded forest and planting such trees close together, forcing the seedlings to “compete” with each other and allowing them to mimic natural environments. The trees are often self-sustaining in just three years.

The Environmental Soldier program now has planted more than 25 million trees. In 2018, the KDF entered into an agreement with the Ministry of Environment and Forestry to adopt five badly stripped forests as “test pilots” for restoration. The first phase of the agreement, according to Kenya’s Capital FM, was the planting and nurturing of 2 million indigenous trees in Kibiku Forest and another 1 million trees in Ololua Forest.

The program has benefits beyond restoring forests to good health. For instance, when the KDF planted more than 5 million trees in the arid and semi-arid areas of Lodwar, Lokichogio, Turkana, Pokot and North Eastern Province, the military’s Corps of Engineers’ Water Drilling Squadron constructed wells in the area that were used to tend to the trees. The wells also provided water for the residents.

Kenyan officials say they have come to regard the Environmental Soldier program as serving a larger purpose — that of maintaining peace in their country. Protection of the environment is the first line of defense in resolving resource-based conflicts, such as those between herders and farmers.

In a 2018 tree planting ceremony Kenya’s first lady, Margaret Kenyatta, said the mission to go green is an urgent one. “This is no longer a waiting game,” she said. “Our actions require urgent, bold, decisive response from all stakeholders, both private and public, to promote behavioral change to address the threats posed by our human actions.”

Kenya’s Water Towers

Kenya’s Water Towers

Kenya’s five major forests are known as the country’s “water towers.” These mountain forest ecosystems — Mount Kenya, Aberdare range, Mau Complex, Cherangani Hills and Mount Elgon — form the containment and natural drainage areas for all but one of Kenya’s main rivers.

The water towers cover less than 2 percent of the total area of Kenya, but they host 40 percent of Kenya’s mammal species, including 70 percent of the threatened ones. The forests host 30 percent of Kenya’s bird species, including half of those that are threatened.

They are the single most important source of water in Kenya for direct human consumption and industrial use. Millions of farmers live on the forest slopes and depend on the rich soil and micro-climatic conditions for crop production.

The rivers flowing from the water towers are the lifeline for major conservation areas in the lowlands. These conservation areas host a diversity of plants and animals.

The water towers provide water to hydroelectric plants and produce 57 percent of Kenya’s total installed electricity capacity.

The decline of forest cover in the water towers has been attributed to illegal logging of indigenous trees for timber and charcoal, forest fires, and encroachment for crop cultivation and settlement.

The restoration and rehabilitation of the five water towers is one of the flagship projects of Vision 2030, Kenya’s long-range growth plan.

Sources: “A review of Kenya’s national policies relevant to climate change adaptation and mitigation Insights from Mount Elgon,” published by the Center for International Forestry Research; Rhino Ark