The sun beat down upon the pristine, white deck of the Galaxy Leader vehicle carrier as it steamed through the Red Sea about 80 kilometers west of Yemen’s port of Hodeidah on November 19, 2023.

The journey surely had the 25 international crew members on edge. Houthi rebels just weeks earlier had begun their lawless assault on global shipping. The Galaxy Leader crew’s worst fears were realized when a charging Mi-171Sh helicopter hovered over the 189-meter ship and deposited several masked gunmen onto the deck. They rushed unchallenged to the bridge and ordered crew members there to get on the floor. Several small Houthi boats then flanked the British-owned, Japanese-operated cargo vessel and forced it into Hodeidah, which the Houthis control.

The 25 Bulgarian, Mexican, Filipino, Romanian and Ukrainian hostages lived in uncertainty until the Houthis released them to Oman after two months of intensive diplomatic wrangling.

The Galaxy Leader’s saga is just one of the better-known instances of commercial ships falling victim to unrelenting attacks by Iran-backed Houthi rebels. Since late 2023, the Houthis have fired missiles and launched armed drones at container ships, bulk carriers, and oil and chemical tankers.

Some attacks damaged their targets; others missed. The rebels sank two bulk carriers in 2024: the Rubymar on February 18 and the Tutor after a June 12 assault. In all, Houthis have launched more than 100 attacks and killed four seafarers between November 2023 and January 2025.

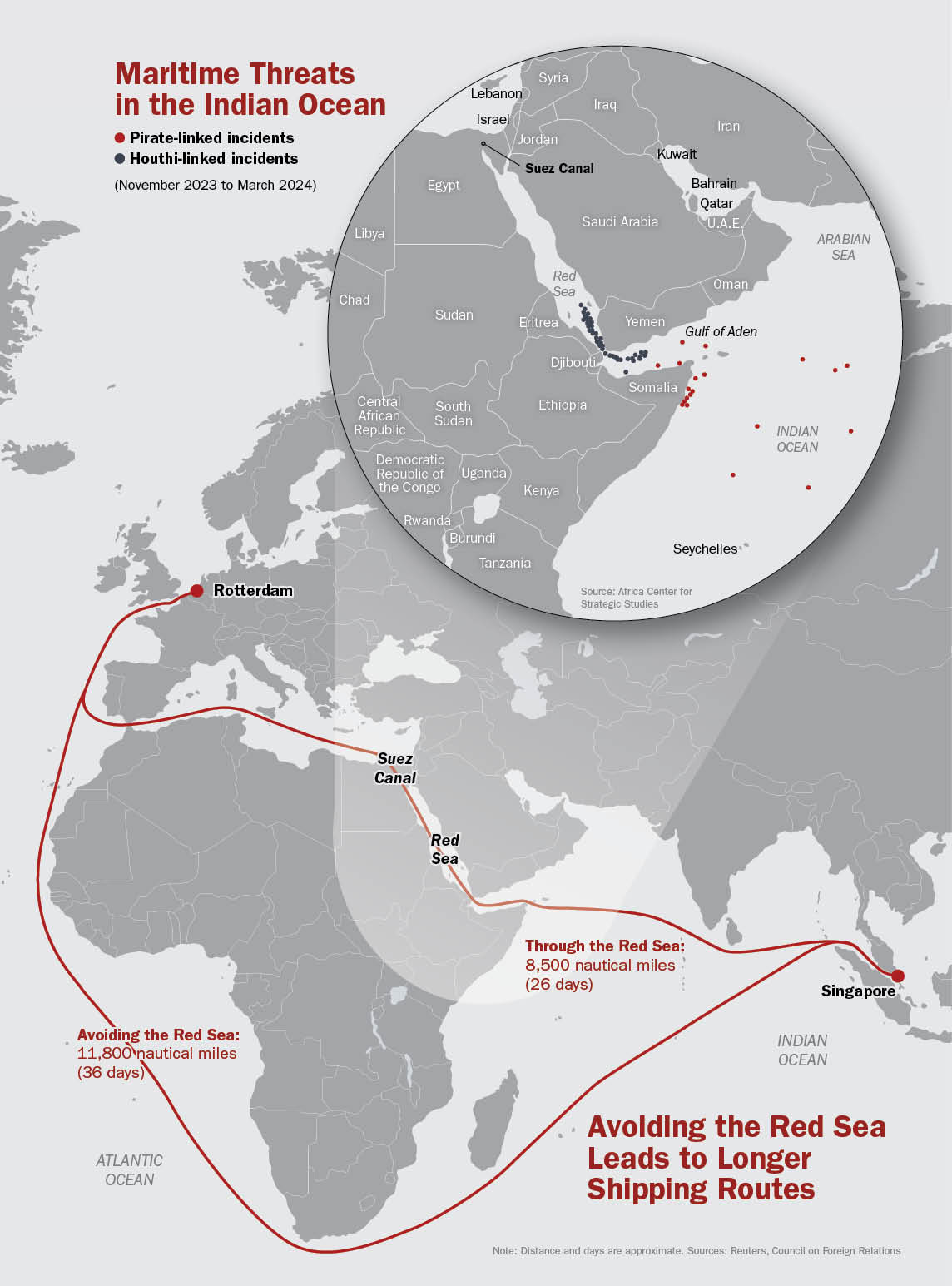

“The attacks have convulsed shipping from the Red Sea through the Gulf of Aden to the Western Indian Ocean, through which 25 percent of global shipping traffic flows,” wrote Francois Vreÿ and Mark Blaine in “Red Sea and Western Indian Ocean Attacks Expose Africa’s Maritime Vulnerability” for the Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

“The repercussions have been immediately visible. Global shipping companies have diverted routes away from the Red Sea, altering shipping flows between the huge global markets of Asia and Europe. Insurance premiums for shipping have surged, raising the costs of goods for consumers in Africa and around the world. Diversions around South Africa can add up to 2 weeks and 6,000 extra nautical miles to a vessel’s journey.”

Observers also note alarming levels of cooperation between the Houthis and Somalia-based al-Shabaab terrorists, who for years have been a threat to ships off Africa’s coast.

A REGIONAL AND GLOBAL SCOURGE

The Red Sea already is an easily disrupted shipping lane with choke points at each end. The sea narrows dramatically in the north as ships squeeze through the Suez Canal. In the south, shipping traffic must traverse the Bab el-Mandeb strait before easing into the Gulf of Aden and the wider Indian Ocean. Any threat to this already-precarious shipping lane can have catastrophic ripple effects worldwide.

The strait sees 15% of global maritime trade pass through it. Shipments of crude oil and related products dropped by more than 50% in the first eight months of 2024, down to 4 million barrels per day from 8.7 million barrels per day in 2023, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

As Houthi attacks on shipping began with the Galaxy Leader in November 2023, the disruption was immediate. One remedy was to bypass the Bab el-Mandeb strait in favor of a spectacularly circuitous route that sent ships around the Cape of Good Hope at Africa’s southern tip. The increase in time and distance add to shipping fuel and insurance costs while delaying delivery of crucial goods to ports all over the world.

The attacks also harm African nations directly. For example, Egypt typically depends on nearly $10 billion in annual revenue from Suez Canal tolls. When ships avoid the Red Sea on the way to Europe or North Africa, those tolls disappear. Egypt’s “overall economic impact from the Suez Canal is about $56 billion pre-Houthis,” Dr. Ian Ralby, CEO of I.R. Consilium, a global maritime resource and security consultancy, told ADF. “That is down about two-thirds. That economic impact is enormous.”

The potential negative effects would be widespread.

“If the Egyptian economy were to fully collapse, it would cause all kinds of ripples in every direction, and so that affects the Middle East, it affects Africa and it affects Europe,” Ralby said.

The inability of ships to safely navigate the Red Sea also has negative ramifications for Sudan. The ongoing civil war there has intensified food insecurity, so if ships can’t reach Port Sudan, civilians are more likely to face starvation and be deprived of medical supplies, he said. Delays in shipments of crucial goods also could harm Ethiopia and Somalia, where conflict has persisted for years.

WHO ARE THE HOUTHIS?

Although the Houthis seem to be relative newcomers to worldwide news reports, their roots go back to the 1990s, when they emerged under the name Ansar Allah, which means “Partisans of God.” Their common name is taken from their late founder, Hussein al-Houthi. His brother, Abdul Malik al-Houthi, now leads the movement. They represent the Zaidis, a sect of Yemen’s Shia Muslim minority, and declare themselves to be part of Iran’s “axis of resistance.”

By the 2000s, Houthi rebels were fighting then-Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh for more autonomy in their homeland in the north. By 2011, Saleh had handed power to Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi, and soon Houthis had seized Yemen’s capital, Sanaa. As the group continued to capture territory, Hadi fled the country and Saudi Arabia feared the Houthis would make Yemen an Iranian satellite, the BBC reported. Despite Arab interventions in the war, more than 4 million people have fled and more than 160,000 have been killed.

The Houthis are generally agreed to be an Iran-backed proxy that opposes Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Although they have been around for decades, the group didn’t gain true global notoriety until they started attacking commercial shipping in the Red Sea. Despite the false narratives that Houthis use for attacking ships, experts agree that the true reason is to galvanize domestic support in a country that’s essentially in chaos.

“Politically, the Houthis need a rally-around-the-flag to mute what had been growing domestic discontent,” Gregory Johnsen, a fellow at the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, D.C., who studied and lived in Yemen for several years, said in an X thread. “Economically, the Houthis want to expand the local war in Yemen, because eventually they need to take either Marib or Shabwa (where Yemen’s oil and gas fields are) in order to have an economic base to survive long term in Yemen.”

The Houthis are a militia who gained control of a country that they can’t govern, so the lack of a war at home makes them “vulnerable to domestic rivals,” Johnsen said.

TERRORISTS COOPERATE ACROSS SEA

TERRORISTS COOPERATE ACROSS SEA

The Houthi threat goes beyond shipping lanes between the Gulf of Aden and the Suez Canal. The group also is known to have found common cause with Somalia’s al-Shabaab terrorist group. A February 2025 United Nations report noted that the two groups had formed a “transactional or opportunistic” relationship. People from both groups had met at least twice in Somalia: in July and September 2024. Al-Shabaab asked for advanced weapons and training. In return, the Houthis asked for an increase in ransom piracy against cargo ships in the Gulf of Aden and off Somalia’s coast.

“During this period, Al-Shabaab was reported to have received some small arms and light weapons and technical expertise from the Houthis,” the U.N. report said. On no fewer than 13 occasions between October 2023 and April 2025, various authorities seized or destroyed weapons transiting between Yemen and Somalia, according to the Africa Center.

Ralby said some of this cooperation exists in an area that has seen money, ideology, people, weapons and drugs move back and forth between East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula for decades. These networks date back to when Osama bin Laden was hiding in Sudan and when al-Shabaab was financing terrorism through charcoal sales to the Middle East. “The Houthis are the product of different factors, but they’ve been around since the ’90s,” Ralby said. “They’re not new. They’re new to a lot of people, so that means that they’ve been building connections for a very long time.”

HOW AFRICA CAN RESPOND

Robust maritime domain awareness is key to establishing order at sea off the coast of Africa, Vreÿ and Blaine said in their Africa Center paper. Africa already has tools in place to establish that awareness. In 2022, two centers began operations. The Regional Maritime Information Fusion Centre (RMIFC) in Madagascar monitors and shares information on suspicious vessels in the region. The Regional Centre for Operational Coordination (RCOC) in Seychelles uses RMIFC data to coordinate security responses in the Western Indian Ocean.

There are five subregional maritime rescue coordination centers and 26 subcenters that cover the entire continental coastline to coordinate search and rescue operations. Western naval coalitions and the Indian Navy have responded during the Houthi crisis, but African navies could do more, Vreÿ and Blaine argue. “Not even Egypt, which has a very capable navy and stands to suffer significant economic losses from the crisis, has deployed a single vessel.”

Despite this, Ralby said African nations have provided crucial support to efforts to counter the Houthi shipping threat. For example, the tiny island nation of Seychelles was among the first 10 nations — and the only African country — to participate in Operation Prosperity Guardian, a U.S.-led multinational naval presence and information-sharing mission responding to the threat.

Information, intelligence and operational support from the RCOC in Seychelles and the RMIFC in Madagascar helped the Indian Navy and multinational naval operations hold the line against piracy, which many feared would surge as the Houthi threat continued, he said.

As Red Sea attacks caused ships to divert, African coastal nations also have done well in providing and managing resources such as fuel while traffic around the Cape of Good Hope increased by 135%, Ralby said. “And so yes, there have been a few incidents that were naturally going to occur when you increase that amount of shipping around an area that has a tendency for high and unpredictable weather. But overall, the African management of the situation has been very good.”