Isis Fighters Leaving Iraq And Syria May Not Pose Primary Threat To Africa

DANIEL HAMPTON, AFRICA CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES

As of late 2018, ISIS had lost 97 percent of the territory it once controlled in Syria and Iraq. More important, it had lost almost all means of revenue generation that came from holding that territory. The flow of fighters moving into Syria came to a virtual standstill.

For as long as ISIS has been a force, people have been asking: What will happen in Africa when ISIS fighters return to their home countries? There are three main scenarios:

Foreign fighters in Syria will return to their African countries of origin, bringing with them a corresponding increase in the threat of domestic terrorist attacks.

ISIS affiliates in Africa will grow stronger as ISIS shifts its center of gravity from Syria to Libya.

The collapse of ISIS in Syria will weaken African ISIS affiliates.

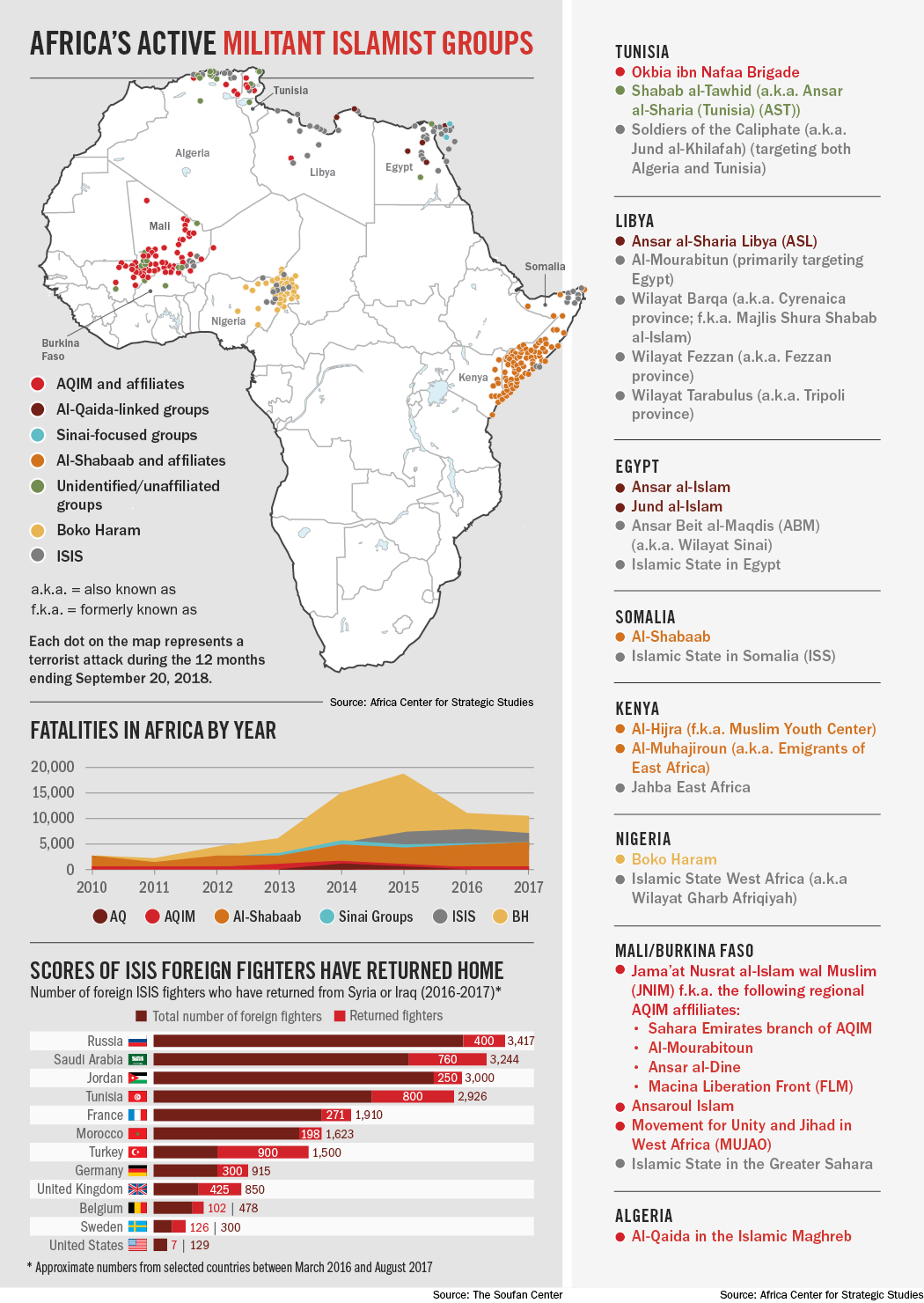

Certainly, there are significant numbers of Africans who went to fight under the ISIS banner in Iraq and Syria. Almost 1,000 foreign fighters have returned to Tunisia and Morocco.

Research conducted at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands assessed that those who traveled to Syria are less likely to see themselves as domestic terrorists than those ISIS sympathizers who stayed at home. Moreover, based on an examination of terrorist attacks that were foiled, there were more than twice as many plots involving homegrown ISIS sympathizers as plots involving foreign fighters who returned home from Syria.

In Tunisia, ISIS and al-Qaida are recruiting a new generation of young people to stage terrorist attacks at home, including one in July 2018 near the Algerian border that left six national guardsmen dead.

“This is primarily homegrown,” Matt Herbert, a partner at Maharbal, a Tunis-based security consulting firm, told The Washington Post. “The majority of Tunisians who survived Libya and Syria have not returned.”

One unexpected turn: The casualty rate of the ISIS warriors has been higher than was predicted.

“We’re not seeing a lot of flow out of the core caliphate because most of those people are dead now,” U.S. Marine Corps Lt. Gen. Kenneth F. McKenzie Jr. told The New York Times. “Some of them are going to go to ground.”

“I’ve been saying for a long time that there won’t be a ‘flood’ of returnees, rather a steady trickle, and that’s what we are seeing,” said Peter Neumann of the International Center for the Study for Radicalization at King’s College London, as reported by the Times.

This is not to say that returning foreign fighters from Syria do not pose a domestic threat, but in looking at the consequences of the collapse of the so-called caliphate on Africa, there are other likely impacts that may pose a greater threat.

ISIS has seven identified affiliates in Africa: Ansar Beit al Maqdis in the Sinai area, Islamic State in Libya, Ansar al-Sharia (Tunisia), ISIL Algeria Province, Islamic State in Greater Sahara, Islamic State in West Africa (a splinter group of Boko Haram) and Islamic State Somalia (a splinter group of al-Shabaab).

There are two main narratives that could play out after the collapse of the ISIS caliphate regarding these affiliates.

One possible outcome is that ISIS will shift its center to the African continent, foreign fighters will reinforce and strengthen existing organizations, and the threat from ISIS will grow.

The other scenario is that without strong central leadership and a geographical and territorial base, coupled with the loss of funding sources upon which the Syrian “caliphate” previously relied, the African ISIS provinces will splinter and the ISIS presence will decline or disappear. This is both the most likely outcome and the most dangerous.

A STRONGER ISIS IN AFRICA?

Although ISIS could grow stronger in Africa, several factors argue against it.

Based on interviews with captured terrorists, authorities know there are many reasons why people join violent extremist organizations (VEOs). It’s usually a combination of push and pull factors.

Push factors are circumstances that push people to violent extremism: unemployment, poverty, lack of access to basic services, marginalization, and human rights abuses at the hands of government security forces.

At the opposite extreme are factors that pull people in: the need for a sense of belonging, a sense of identity and self-worth, a purpose in life, an ideology. Ideology is just one factor of many, and it is often not the predominant reason why people decide to fight for these organizations. Moreover, research indicates that the dominant ideological influence for militant Islam in Africa is not ISIS teachings, but the Wahhabi sect, a branch of strictly orthodox Sunnis.

There is plenty of evidence to suggest that, by and large, ISIS is not well-rooted in the communities where Africa’s most active violent Islamist groups operate. The most lethal violent Islamist groups in Africa, Boko Haram and al-Shabaab, predate ISIS and sprung from their local communities. They understand the grievances, and do not rely on ISIS for resources or operational support.

Evidence shows that foreign fighters are moving from Syria to Africa, but most will likely attempt to join another armed group and continue to fight rather than return to their country of origin. However, this does not mean they will necessarily join another ISIS-affiliated group.

With the loss of Sirte in Libya and the lack of resources from ISIS, many of these former ISIS fighters might gravitate toward Mali, the Lake Chad Basin and Somalia. The potential is high that the collapse of the “caliphate” could result in the growth of other VEOs in Africa and strengthen those that are already the most active and the most violent. So although ISIS may wither, the threat from other extremist groups will not.

Analysts are not sure how many African militants went to fight in Syria and Libya, estimating as few as 5,300 fighters to as many as 8,500. That number is the equivalent of six to 10 United Nations battalions — more troops than some entire countries have in their army. They represent an undeniable threat.

So whether ISIS affiliates strengthen in Africa, or whether they wane and other groups profit and grow at their expense, the questions to address are: “What can we do to improve security in the region?” and “How do we address the impact and implications on African security resulting from the collapse of the ISIS caliphate?” Four suggestions come to mind:

Improve multinational cooperation on tracking terrorist movements, border security, intelligence sharing and early warning systems.

Continue to improve multinational coordination and pursuit of shared strategic objectives to address the threats within Libya, Mali, the Lake Chad Basin and Somalia.

Improve reintegration efforts for returning or captured fighters. If the conditions that led to violent extremism have not improved, deradicalization is unlikely to produce results. Current research shows a 60 percent recidivism rate for returned foreign fighters, and that percentage is even higher for those who were incarcerated.

Prioritize and allocate resources to create a better balance of the security-governance-development nexus. Use of force alone is not a solution. The three parts of the nexus need to grow simultaneously, and they must be integrated within a strategic plan. That plan needs to be part of a national strategy, and ideally, within a larger multinational strategy.

Fundamentally, improving security is about resources. Resources — money, personnel, time, energy and effort — are the best indicators of priorities. However, if these resources are applied only to increasing the capability and capacity of the security forces without addressing the underlying causes of the conflict, failure will surely follow.

Daniel Hampton, a retired U.S. Army colonel, is the chief of staff at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, National Defense University. His military career included assignments in Eswatini, Lesotho, Malawi, South Africa and Zimbabwe. He is the author of “Creating Sustainable Peacekeeping Capacity in Africa,” an Africa Center for Strategic Studies security brief.

Daniel Hampton, a retired U.S. Army colonel, is the chief of staff at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, National Defense University. His military career included assignments in Eswatini, Lesotho, Malawi, South Africa and Zimbabwe. He is the author of “Creating Sustainable Peacekeeping Capacity in Africa,” an Africa Center for Strategic Studies security brief.