ADF STAFF

Africa may have already gotten its first experience with artificial intelligence on the battlefield in mid-2020. That’s when Turkish-made autonomous Kargu-2 drones tracked and killed members of Libyan Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar’s forces as they retreated from their failed siege of Tripoli, according to reports.

Although the exact nature of the attack remains in dispute — some observers question whether the drones truly were acting on their own — a growing number of experts predict artificial intelligence (AI) will play an increasing role in Africa, on and off the battlefield.

“AI is not coming to Africa, it’s already here. And its role is only likely to grow in the coming years,” Abdul Hakeem Ajijola, chair of the African Union’s Cyber Experts Group, recently told the Africa Center for Strategic Studies (ACSS).

As the use of AI expands, governments and regulators have been slow to adopt the rules needed to govern its use.

“On AI policy, there are no countries in the world that are prepared,” Rob Floyd, director of innovation and digital policy for the Ghana-based Africa Center for Economic Transformation, told ADF.

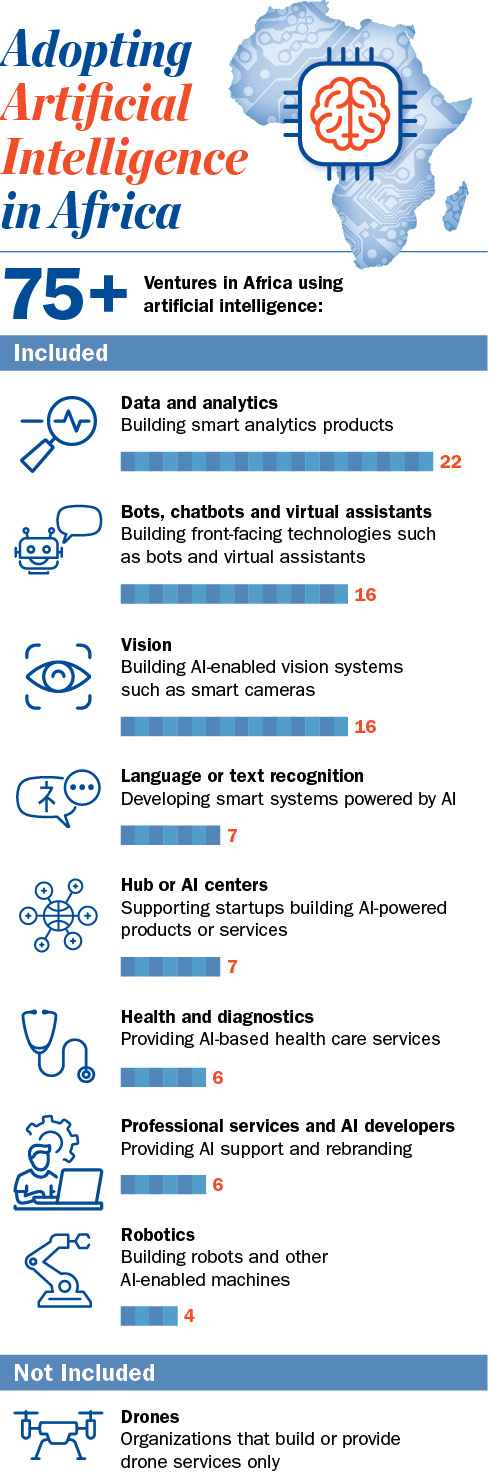

More than 2,400 African organizations already are working with AI across a variety of sectors, from agriculture and health to law enforcement and security. AI monitors crops for disease, guides drones delivering medications to distant villages and scans crowds for potential terrorists. AI’s capacity for digesting huge amounts of data quickly and finding patterns within it makes the technology a valuable tool, according to Ajijola and other experts.

More than 2,400 African organizations already are working with AI across a variety of sectors, from agriculture and health to law enforcement and security. AI monitors crops for disease, guides drones delivering medications to distant villages and scans crowds for potential terrorists. AI’s capacity for digesting huge amounts of data quickly and finding patterns within it makes the technology a valuable tool, according to Ajijola and other experts.

That said, the exact meaning of AI, like the technology itself, continues to evolve.

“There is no agreed definition for artificial intelligence right now,” South Africa-based attorney and researcher Nokuthula Olorunju, a research fellow at Research ICT Africa, recently told ACSS. “We’re discovering it as we go along.”

Current AI technology ranges from artificial narrow intelligence, such as online systems that provide real-time traffic updates, to generative AI such as ChatGPT, which can create text, video and audio content that can be used to spread misinformation and drive conflict.

One thing AI researchers agree on: Like electricity, the internet or a four-wheel-drive vehicle, AI is a tool that only is as good or bad as the humans who use it.

“The scare around AI is because of the proliferation of harms that we see being caused through the use of AI,” Olorunju said. “It boils down to the safety and security issues that are caused when AI is allowed to run free. AI currently exists in a legal gray area, and the law is not able to keep up.”

AI and Analysis

AI experts are quick to point out that the technology is no substitute for human knowledge, intuition and creativity.

“It’s actually pattern recognition,” Ajijola said.

For all its capabilities, AI’s greatest strength may be its ability to sort the wheat from piles of digital chaff quickly, efficiently and at a scale that human beings could never achieve.

Whether the data represents terrorists’ communications, radar readings of ship traffic or the movements of poachers in wildlife areas, AI’s capacity for pattern recognition provides human users with data that makes security actions more precise and less risky.

In Malawi’s Liwonde National Park, for example, AI-powered EarthRanger software studies poaching patterns within the park and, using predictive analytics, alerts rangers to potential surges in activity so they can develop their anti-poaching strategy.

The system’s “poacher cams” can distinguish between people and animals moving through the park, letting rangers identify poachers without having to put themselves in danger.

The Nigerian Navy has begun integrating AI into its systems to strengthen its operational capacity and keep pace with evolving technology.

Nigerian Chief of Naval Staff Vice Adm. Emmanuel Ogalla said that AI can predict the most fuel-efficient way to operate a ship. Integrated into the ship’s radar operations or threat-detection systems, it can help operators process information faster and better understand how to respond to a threat at sea. In that way, AI can improve the navy’s ability to fight illegal fishing and drug trafficking in the Gulf of Guinea, experts say.

Ogalla also highlighted another benefit AI will provide to the Nigerian Navy: predictive maintenance. As AI monitors a ship’s systems, it can identify potential equipment failures and alert the crew to the need for maintenance, catching problems when they still are small. Doing so will ensure that ships remain ready rather than sitting docked for repairs.

“The Nigerian Navy must continue to adopt and integrate these technologies in order to maintain a competitive edge during operations,” Ogalla told the Nigerian newspaper Leadership.

For Ajijola, AI’s processing capacity and pattern recognition abilities let analysts focus on planning and strategy rather than spending their days sifting through mountains of data.

“We must find ways to ease the burden on analysts so they’re more efficient,” Ajijola said.

On the Battlefield

Perhaps more than any other technology that uses AI, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) — drones — represent the promise and the threat inherent in artificial intelligence. In that respect, an AI-powered arms race may already be in motion across Africa as militaries stock up on drone technology to supplement ground and maritime forces.

“Despite global calls for a ban on similar weapons, the proliferation of systems like the Kargu-2 [rotary wing attack drone] is likely only beginning,” analysts Nathaniel Allen and Marian “Ify” Okpali wrote for the Brookings Institution in 2022.

Militaries across Africa have bought or placed orders for the Kargu-2 and the larger Turkish-made Bayraktar TB2 drones. The list of countries adding the Turkish drones to their arsenals includes Ethiopia, Morocco, Rwanda and Togo.

Although the current crop of drones is not publicly acknowledged to have AI capabilities, drone makers already are promoting the next generation of drones that definitely will use AI.

South Africa’s Paramount Group introduced its AI-driven N-Raven drone system in 2021 with the capacity to swarm targets. Although the UAVs can be used for reconnaissance, each is large enough to carry up to a 15-kilogram payload, creating the potential for attack by multiple drones coordinating with each other to find and eliminate targets while overwhelming the target’s defenses.

“These are new machines of war,” Ajijola said.

Experts say the use of AI-powered drones and similar automated, free-range weapons raises an important question: Who’s responsible for their actions?

“At the end of the day, where does the buck stop?” Olorunju said. “Who has accountability? Who bears responsibility — is it the country? The manufacturer?”

Observers say it’s only a matter of time until AI technology finds its way into the hands of insurgents, who could then use it to terrorize communities or attack government institutions without exposing their own fighters. Terrorist groups such as Boko Haram have used non-AI drones to conduct reconnaissance and film battles with government forces.

“Non-state actors will adopt these technologies themselves and come up with clever ways to exploit or negate them,” wrote Allen and Okpali. “Artificial intelligence will be used in combination with equally influential, but less flashy inventions such as the AK-47, the nonstandard tactical vehicle, and the IED to enable new tactics that take advantage or exploit trends towards better sensing capabilities and increased mobility.”

Challenges

The prospect of extremists adopting AI-powered weapons is just one of the challenges African countries face as AI use increases across the continent.

As technology like AI develops, it heightens the threat to cybersecurity, researcher Emmanuel Arakpogun wrote in a study published by Northumbria University.

“State or individual actors could cripple critical infrastructure in a manner that threatens the existence of a nation,” he wrote.

AI-driven attacks on critical infrastructure such as power, water and banking could happen at a speed and with a frequency that human cybersecurity teams would struggle to match. Researchers say AI systems could fill that gap, monitoring systems around the clock and alerting its human counterparts when suspicious activity appears.

Beyond physical infrastructure, nations face AI-powered attacks on their democratic infrastructure. Generative AI systems already can create so-called deepfake videos along with realistic looking fake news articles and other content aimed at stoking conflict, undermining leaders, and sowing suspicion and violence across societies.

“Cruise missiles can take down a building, but AI can ‘hack’ the electorate to convince countries to elect the wrong people,” Ajijola said.

Further complicating things: “Generative AI leaves few fingerprints,” Melissa Fleming, the United Nations’ global communications chief, recently told the U.N. “Generative AI holds massive potential for voter manipulation.”

Experts agree that African governments can use AI to defend against online attacks, but they also note that Africa needs to catch up in terms of educating skilled programmers and funding projects. That is changing, however.

The recently opened U.N.-funded African Research Centre on Artificial Intelligence in Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo, joins a growing list of institutes from Morocco to South Africa and from Ghana to Rwanda that seek to expand Africa’s homegrown capacity for meeting the promise and threats of AI.

African-made AI has the potential to create jobs and provide employment to millions of people on the continent, Floyd said. That, along with AI-aided innovations in agriculture, infrastructure, government spending and more, could reduce conflicts over resources that drive insecurity in Africa, he added.

“If people are more productive and resources are used more productively, one would hope that you would have a society that is more in harmony,” Floyd told ADF.

Of Africa’s 2,400 AI-related companies, more than 40% are startups that already have received hundreds of millions of dollars in seed funding. That’s a sliver of the $79.2 billion spent globally on AI in 2022, and much of it has gone into developing financial technology in Nigeria, a hub for online financial fraud, according to Arakpogun.

Although Nigeria has attracted the largest amount of AI-related investment capital, South Africa has generated the largest number of AI-related companies, followed by Nigeria and Kenya. Egypt, Ghana, Tunisia and Zimbabwe also are among the continent’s top AI pioneers.

In order to avoid a repeat of the missed opportunities from the previous industrial revolutions that have left a negative legacy for African countries, governments must create an enabling environment for these AI start-ups to flourish and accelerate the socio-economic development of Africa.” ~ Emmanuel Arakpogun, researcher

“In order to avoid a repeat of the missed opportunities from the previous industrial revolutions that have left a negative legacy for African countries, governments must create an enabling environment for these AI start-ups to flourish and accelerate the socio-economic development of Africa,” Arakpogun wrote.

The Future

As African countries look toward their future relationship with AI, it’s imperative that they develop strategies to address the good and bad aspects of the technology, experts say.

Mauritius led the way in 2018 when it published its national AI strategy, describing the technology as creating a new pillar for development for decades to come. Other African countries have followed, although none has achieved Mauritius’ level of preparedness.

In 2002, Oxford Insights ranked every country on a 100-point scale for its readiness to use AI to deliver public services. Mauritius, with a score of 53.8, and South Africa (47.74), Egypt (49.42), and Tunisia (46.81) are the only African countries to exceed the global average of 44.6.

The African Working Group on AI hopes to construct a unified strategy for the continent, an important step toward encouraging nations to share their data to optimize AI systems.

“One of the biggest challenges in Africa is the quality of and access to data,” Floyd said. “Economic data is often years out of date.”

The African Union’s AI for Africa Blueprint, developed in 2021, spells out the opportunities and challenges of using AI and proposes key principles to guide its use in the future. Any AI strategy developed by African countries needs to reflect African values, not be a “cut-and-paste” from elsewhere, experts say.

“This is not a theory. This is not in some other part of the world,” Ajijola said. “We need to determine which African philosophies will guide development of AI on the continent. The digital revolution’s ultimate legacy in security will be how it is used.”