ADF STAFF

Coup attempts were frequent in Africa in the post-independence and Cold War periods.

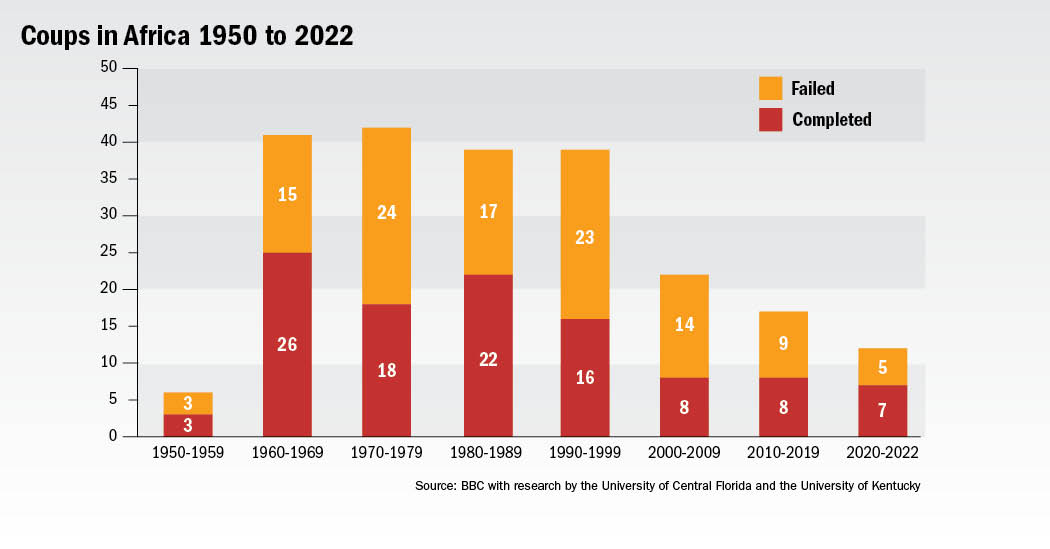

By comparison, the past 20 or so years have been quiet. From 2011 through 2020, the continent averaged fewer than one completed coup per year. But since then, the relative stability has given way to what looks like a sharp reemergence of coup attempts.

From January 1, 2020, through December 2022, there were a dozen coup attempts on the continent. Of those, six resulted in an unconstitutional change in government at the hands of military officers.

The trend has caused concern among continental and regional organizations. The development prompted the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) to hold an emergency summit in Accra, Ghana, in February 2022 to discuss the issue.

ECOWAS Chairman and Ghanaian President Nana Akufo-Addo told the summit that coups had become “contagious” and that the trend “must be contained before it devastates our whole region,” according to Al-Jazeera.

Likewise, Moussa Faki Mahamat, chairman of the African Union Commission, voiced his concern about “the resurgence of unconstitutional changes of government.”

Coups are complex and disruptive events. Their causes can be varied, and preventing them can be difficult. But understanding what causes coups is the first step in building professional militaries that have the knowledge, training and desire to avoid them.

When Is a Coup a Coup?

A coup occurs when organized forces, be they military or political, act to unseat a ruling national government. Coups in Africa most often involve action by a faction within the nation’s military. Some are violent; others involve security officers co-opting national communications channels and detaining leaders and high-ranking government officials.

Coups typically are considered to be complete if the disruption lasts seven days or more. Other experts say plotters must stay in power at least a month. Regardless, studies have shown that about half of all coups in Africa over the past several decades were completed. That trend held for the continent’s most recent spate of coups as well.

How Often Do Coups Occur?

Coups are not unique to African nations. They have happened in Asia, Europe and South America over the years. A look at coup attempts in Africa since 1950 shows a period of relative calm until about 1963, which could be described as the continent’s post-independence period. From 1960 through 1999, coup attempts averaged just over 40 per decade.

in 2021. AFP/GETTY IMAGES

The ‘Coup Trap’

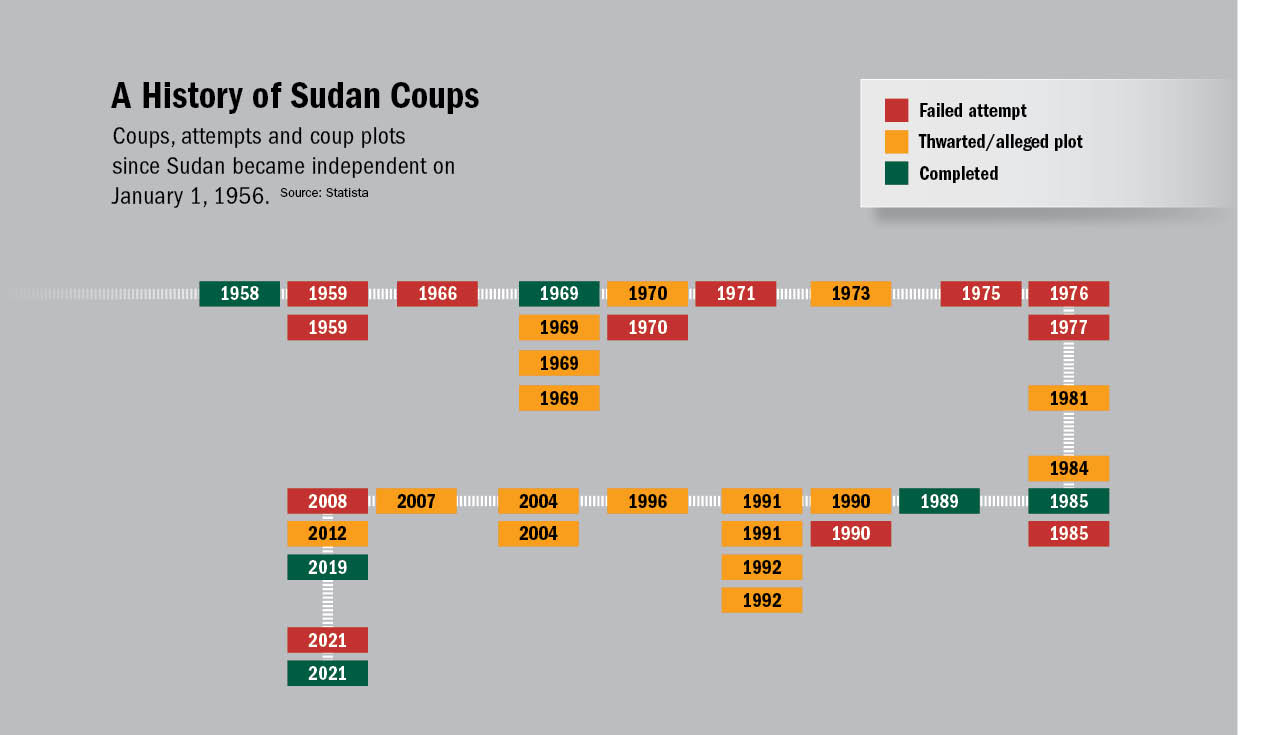

History has shown that once coups take root in a country, it tends to be easier for them to reoccur. Researchers have studied the phenomenon and given it a name: the “coup trap.” Sudan’s history serves as a useful illustration.

Between 1958 and 1971, Sudan experienced 11 failed, thwarted or completed coups. Four plots — one completed and three that were thwarted — took place in 1969 alone. Coup plots also clustered in 1984-1985 and in 1991. Sustained instability returned to Sudan in 2019 in the aftermath of the overthrow of longtime dictator Omar al-Bashir, and it persists even now as military officials and civilian leaders try to hammer out a plan for a return to civilian rule.

In fact, Sudan leads the world in coup attempts between 1945 and 2021, according to information compiled by the research portal Statista.

Legacies of Coups

Once a coup takes place, it tends to create, rather than solve, problems. If military officers overthrow a civilian government — particularly one that was democratically elected — the military leaders likely will be seen as illegitimate. An inability to justify their actions could put the nation at risk for further coups, according to a December 2021 report by Sean M. Zeigler on the Rand Blog.

“Most often, soldiers present themselves as saviors of their countries, accusing deposed regimes of corruption, perfidy, and malfeasance,” Zeigler wrote.

Also, military seizures commonly include statements that the junta’s rule will be temporary, the blog post states. Militaries will describe their new regimes as caretakers merely overseeing and keeping order as the nation eventually restores civilian rule through new elections.

“In many cases, transitional military councils are formed to oversee transitions to democracy, some of which do not materialize,” Zeigler wrote.

The impact that coups have on a nation can be far-reaching. Coups can affect the economy, diplomatic relations and, in some cases, set off a cycle of instability. Below are some ways coups can hurt countries.

Suspension of aid: Many nations and nongovernmental organizations are forbidden from providing aid to a government that comes to power as a result of a coup. When aid is suspended, it takes money away from projects related to national security, public health, agriculture and the energy sector. Sudan, for example, lost nearly $4.4 billion in aid pledged by the international community in the eight months after its 2021 coup.

Harm to the economy: History shows that businesses are less likely to invest in a country or expand trade when there is a climate of insecurity. Insecurity, fear and uncertainty form a toxic brew that could repress economic activity and cause a country to fall into a recession. A study of 94 countries by the Stockholm Institute of Transition Economics found that in democratic countries that experienced a coup, individual income growth was smaller in the decade after the coup than it was in countries that didn’t experience one.

Diplomatic isolation: Many regional, continental and international organizations suspend member states after a nondemocratic transfer of power. For example, after its 2021 coup d’état, Burkina Faso was suspended from the African Union, the Economic Community of West African States, the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie and other groups. This means the country lost the right to vote on or influence economic issues that might have been crucial to its future viability. Also, countries might lose the right to host prestigious economic, diplomatic and sporting events that bring in tourism money. For example, the African Cup of Nations football tournament, one of the premier sporting events on the continent, was moved in the wake of a coup. Having major events relocated due to insecurity can disrupt the social fabric of a society and also hurt businesses that depend on associated revenues, thus harming the national economy.

AFP/GETTY IMAGES

Challenge of governance: When military officers take the reins of power, they do more than just dislodge a ruler or government they consider to be unacceptable. They are left with control of a vast governmental bureaucracy that includes departments and ministries far outside the familiar realm of military operations. Such governments also depend on diplomatic relationships across borders and regions. Disrupting these institutions and relationships can harm the nation and its people.

Furthermore, in his 2020 article, “No Easy Way Out: The Effect of Military Coups on State Repression,” for The Journal of Politics, researcher Jean Lachapelle writes that “coups increase state repression, even when they target repressive autocrats.”

Coups are regularly followed by actions such as jailing dissidents, violent crackdowns on protests, and constricting such rights as free speech and free press. Lachapelle said historical research shows that military coup leaders tend to use a particularly heavy hand against their people.

“Militaries are often ill-equipped to police social unrest. Indeed, scholars have found that regimes ruled by the military tend to be more repressive than other types of regimes,” he wrote. “Moreover, a coup typically relaxes constraints on executive power in the months following it because the military often rules by decree; such reduction of executive constraint might increase repression.”