Military force alone won’t eliminate Boko Haram; the country must address the problems that led to the group’s creation.

DR. HUSSEIN SOLOMON

Since the insurgency started in 2009, the extremist group Boko Haram has killed tens of thousands and forced 2.6 million people from their homes. The group is the single biggest threat to peace and security in Nigeria.

But Nigeria’s military and civilian leaders agree that stopping Boko Haram will require more than just bullets and bombs. “You can never solve any of these problems with military solutions,” said Gen. Martin Luther Agwai, Nigeria’s former chief of defense staff. “It is a political issue, it is a social issue, it is an economic issue, and until these issues are addressed, the military can never give you a solution.”

Africa’s men and women in uniform still need to understand the limits of force when responding to extremist groups such as al-Shabaab, Ansar al-Dine, al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb and Boko Haram. Although military force is an essential component of a broad counterterrorism strategy, it can never on its own deliver peace and prosperity. The central purpose of such armed force is to contain war within a limited area and win that war — not promote peace. Ending the violence of the extremists is its primary mission.

However, this does not end the threat posed, given the structural conditions fueling such extremism. This containment of war provides the conditions on the ground for other government departments, civil society organizations and the international community to work toward ending the structural conditions fueling violence.

Understanding the Roots of Boko Haram

The origins of Boko Haram go back to 1802-1804, when religious teacher and ethnic Fulani herder Usman dan Fodio declared his jihad to purify Islam. In the process, he established the Sokoto Caliphate. Many in the Boko Haram movement cite re-establishing this caliphate as their principal goal.

More recently, the Maitatsine uprisings of 1980 in Kano, 1982 in Kaduna and Bulumkutu, 1984 in Yola, and 1985 in Bauchi represent an effort to impose a religious ideology on a secular Nigerian state. These echo Boko Haram’s attempt to force the national government in Abuja to accept its brand of Islamic Sharia across all 36 states in Nigeria.

Between 1999 and 2008, 28 religious conflicts were reported — the most prominent being the recurrent violence between Muslims and Christians in Jos.

Religion, however, does not exist in a historical vacuum. It is interconnected with issues including ethnicity, politics, economics, migration and violence. Religious differences often have been used by politicians and other leaders to further their own goals. To understand the recurrent religious violence in northern Nigeria, we need to explore the context in which this Islamist fundamentalism thrives.

Entrenched Inequality

One such structural driver is economics. It is no coincidence that northern Nigeria has been prone to radical uprisings — it happens to be the poorest part of the country. Twenty-seven percent of the population in the south live in poverty, compared with 72 percent in the north. The north’s precarious economic situation has been further undermined by desert encroachment, recurrent drought and a rinderpest cattle disease pandemic.

The growing impoverishment of the citizenry stands in sharp contrast to the growing wealth of the political elite. Since the end of military rule in 1999 up to the Goodluck Jonathan administration, Nigerian politicians have reportedly embezzled between $4 billion and $8 billion per year. This adds to the alienation between state and citizen, where the state is viewed as illegitimate. Under these circumstances, one can understand the resonance of the Boko Haram rhetoric when they say the Nigerian state is taghut, or evil.

From here it is a small step to further argue that the Western secular state has failed. Indeed, it is precisely the failure of governance to guarantee security, with attendant rising criminality, which also resulted in northern states implementing Sharia. Boko Haram’s discourses for Sharia would have had scant appeal had successive governments provided basic security to its citizens — especially those in the north.

“The sooner we deliver economic reforms and greater prosperity to all Nigerians, the sooner we can achieve more inclusive society and minimize societal divisions and grievances,” said Dr. Bukola Saraki, president of Nigeria’s Senate.

Defeating Boko Haram won’t be enough to restore order to Nigeria. The nongovernmental organization International Crisis Group says Nigeria must return government administration to marginalized peripheries, “so as to provide crucial basic services — security, rule of law, education and health — and address factors that push individuals to join movements like Boko Haram.”

Identity as a Weapon

Another structural factor is the politics of identity. Nigeria’s 190 million people are divided into more than 500 ethnic groups speaking 250 to 500 languages. The population is further divided along religious lines with 50 percent being Muslim, 40 percent Christian and 10 percent adhering to various indigenous faith traditions. To compound matters further, these differences are mutually reinforcing where ethnic, regional and religious identity markers serve to heighten divisions.

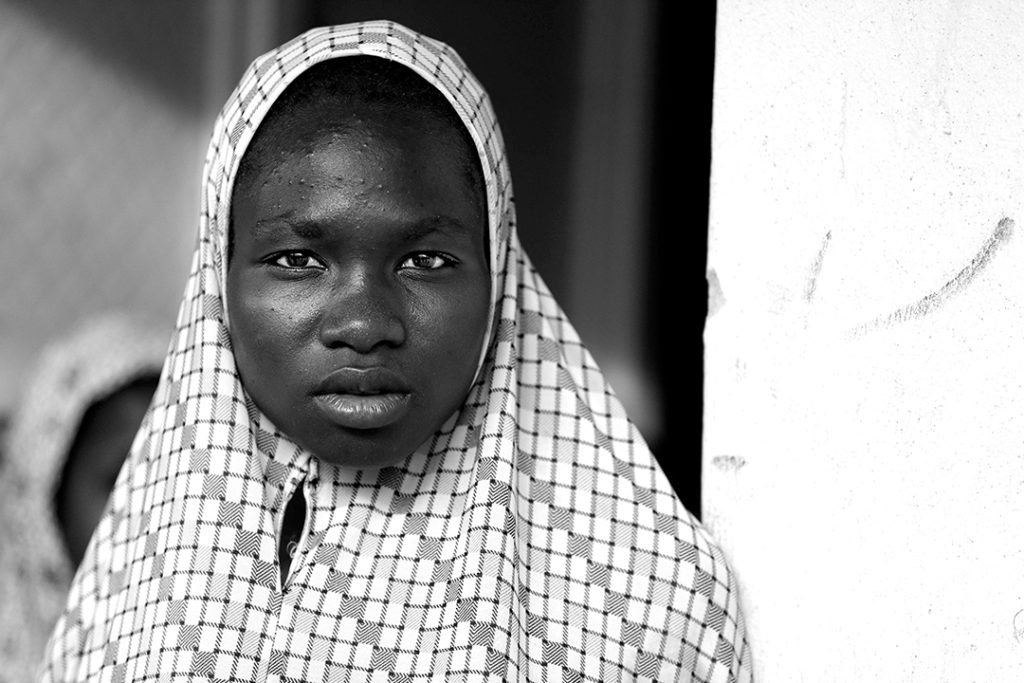

Nigerian Chibok schoolgirls in Abuja, Nigeria, in May 2017. [THE ASSOCIATED PRESS]

The consequence of the exclusionary nature of the Nigerian state is clearly seen in narratives among ordinary Nigerians when explaining the violence. Religion, ethnic and regional identities all play a part. While the popular media has portrayed the conflict as a Muslim-versus-Christian issue, there is another ethnic dimension to the conflict: a case of reinforcing fault lines. The Islamist Boko Haram may be targeting Christians living in the north; however, the perception among the Igbo is that the Hausa Fulani and Kanuri Boko Haram are targeting the Igbo ethnic group — that this is systematic ethnic cleansing.

This perception is given added credence by Corinne Dufka, a senior West Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch. After extensive research on the victims of Boko Haram violence, Dufka believes that Boko Haram is killing people in northern Nigeria based on their religion and ethnicity.

The conclusion is inescapable: No military-centered response will bring about sustainable peace in northern Nigeria unless the underlying structural variables — economics, governance and identity — also are addressed. In a similar vein, the countering violent extremism narrative will not find traction unless issues of poverty, corruption and virulent ethnic nationalism are resolved.

Dr. Hussein Solomon is senior professor in the Department of Political Studies and Governance at the University of the Free State, Republic of South Africa.

Dr. Hussein Solomon is senior professor in the Department of Political Studies and Governance at the University of the Free State, Republic of South Africa.