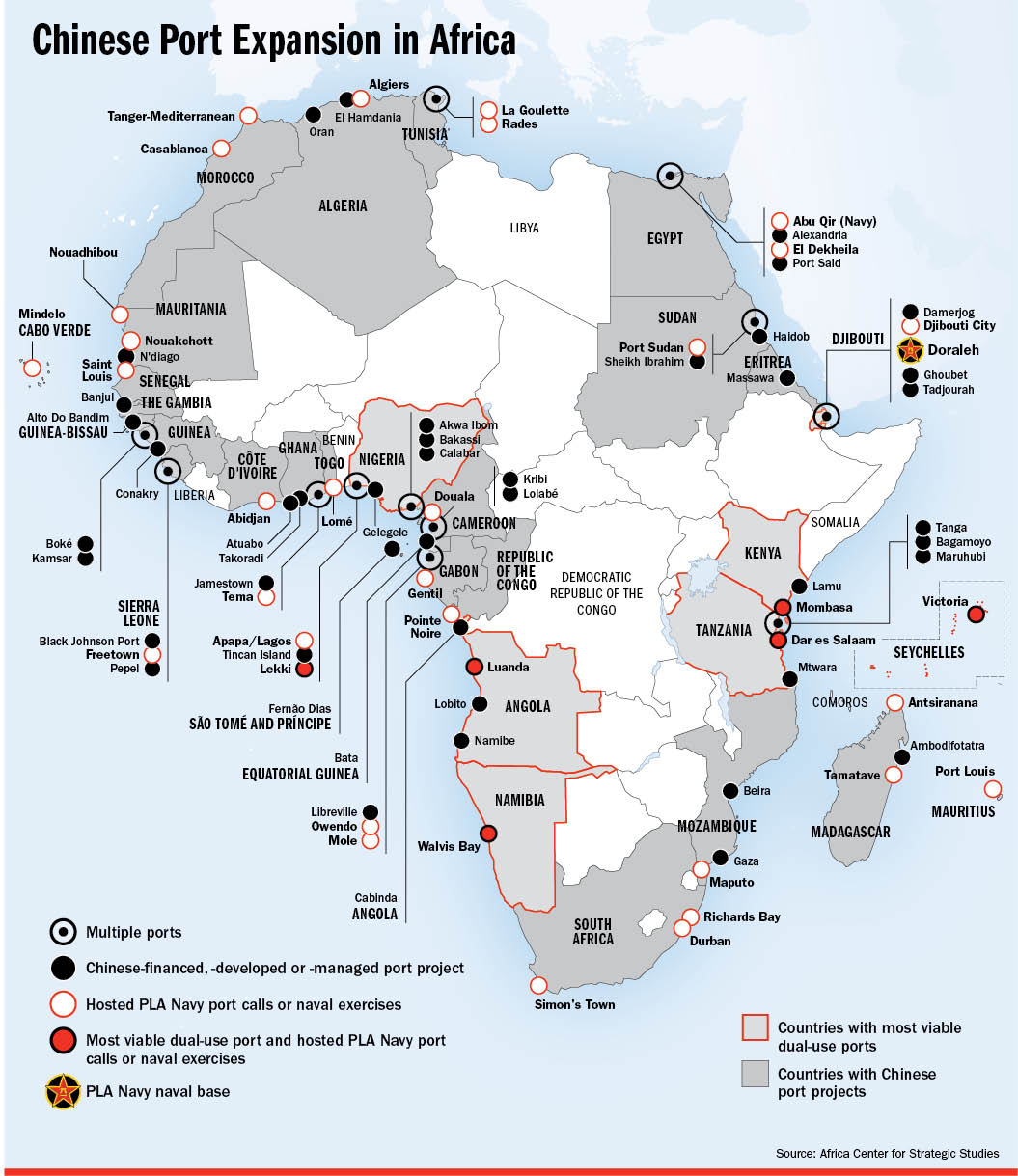

Chinese state-owned companies hold stakes in up to 78 of Africa’s 231 ports, a presence that raises concerns about national sovereignty and China’s designs on expanding its military footprint.

China’s port developments are concentrated in 32 African countries. West Africa has 35, compared to 17 in East Africa, 15 in Southern Africa and 11 in North Africa. By comparison, Latin America and the Caribbean host 10 Chinese-built or operated ports. Asian countries host 24.

China’s expansive port development in Africa raises concerns about the possibility of repurposing commercial ports for military use given the close relationship between Chinese port-building firms and China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA). China’s development of Djibouti’s Doraleh Port, long marketed as a purely commercial venture, was extended to accommodate a naval facility in 2017. It became China’s first known overseas military base two months after the main port opened. There is widespread speculation that China could replicate this model for future basing arrangements elsewhere on the continent.

This raises concerns about China’s broader geostrategic aims with its port development and stokes Africans’ widely held aversion to being pulled into geostrategic rivalries. There also is a growing wariness of hosting more foreign bases in Africa. This underscores the mounting interest in scrutinizing China’s port development and dual-use military basing scenarios.

In some sites, Chinese companies share ownership and dominate entire port development enterprises through financing, construction and operations. Large conglomerates such as China Communications Construction Corp. will win work as prime contractors and hand out subcontracts to subsidiaries such as the China Harbor Engineering Co. (CHEC).

This is the case in one of West Africa’s busiest ports, Nigeria’s Lekki Deep Sea Port. CHEC did the construction and engineering, secured loan financing from the China Development Bank, and took a 54% financial stake in the port, which it operates on a 16-year lease, although the terminal is operated by a French firm, CMA CGM.

China gains as much as $13 in trade revenue for every $1 it invests in ports. A company holding an operating lease or concession agreement reaps not only the financial benefits of all trade passing through that port but also can control access. The operator allocates piers, accepts or denies port calls, and can offer preferential rates and services for its nation’s vessels and cargo. Control over port operations by an external actor raises obvious sovereignty and security concerns. This is why some countries forbid foreign port operators on national security grounds.

Chinese companies hold operating concessions in 10 African ports. Despite the risks over loss of control, the trend is toward privatizing port operations for improved efficiency. Delays and poor management of African ports are estimated to raise handling costs by 50% over global rates. However, most concessions and operating contracts awarded in Africa and elsewhere require open access, so that surface operators cannot provide special access to national interests.

The Plan Behind China’s Ports Strategy

China’s strategic priorities involving foreign ports are laid out in its Five-Year Plans. The 2021 to 2025 Five-Year Plan talks about a “connectivity framework of six corridors, six routes, and multiple countries and ports” to advance Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) construction. Notably, three of these six corridors run through Africa, landing in East Africa (Kenya and Tanzania), Egypt and the Suez region, and Tunisia. This reinforces the central role that the continent plays in China’s global ambitions. The plan articulates a vision to build China into “a strong maritime country” — part of its larger ambition to be seen as a great power.

China’s focus on African port development was facilitated by the “Go Out” strategy, a government initiative to provide state backing — including huge subsidies — for state-owned companies to capture new markets, especially in the developing world. The BRI, China’s global effort to connect new trade corridors to its economy, is a product of Go Out, sometimes referred to as “Go Global.”

Africa has been a central feature of the Go Out strategy, where port infrastructure was a major impediment to expanding Africa-China trade. Heavy Chinese government subsidies and political backing encouraged Chinese shippers and port builders to seek footholds on the continent. They benefited from robust government and party-to-party ties that China cultivated over time. Africa became highly attractive to China’s state-owned enterprises, despite the many risks of doing business on the continent.

China’s port development strategy also has linked Africa’s 16 landlocked countries via Chinese-built inland transport infrastructure, which helps get goods and resources to market and vice versa.

Chinese companies also capitalized on opportunities to export their technologies and expertise. They positioned themselves as dominant players in building export infrastructure that African countries came to increasingly depend on to conduct foreign trade. This has created political windfalls for China. As a senior African Union diplomat said, “African dependence on Chinese export infrastructure makes African countries amenable to supporting Chinese global interests and less inclined to taking sides against it or supporting sanctions.”

Military Engagement

China’s growing footprint in African ports also advances its military objectives. Some of the 78 port sites that Chinese companies are involved in can berth PLA Navy vessels. Others can dock PLA Navy vessels on port calls.

Some of these ports have been staging grounds for PLA military exercises. These include the ports of Dar es Salaam (Tanzania), Lagos (Nigeria), Durban (South Africa) and Doraleh. Chinese troops also have used naval and land facilities for some of their drills, including Tanzania’s Kigamboni Naval Base, Mapinga Comprehensive Military Training Center and Ngerengere Air Force Base — all built by Chinese companies. The Awash Arba War Technical School has served a similar purpose in Ethiopia, as have bases in other countries. In total, the PLA has conducted 55 port calls and 19 bilateral and multilateral military exercises in Africa since 2000.

Beyond direct military engagements, Chinese companies handle military logistics in many African ports. For example, Chinese state-owned enterprise Hutchison Ports has a 38-year concession from the Egyptian Navy to operate a terminal at the Abu Qir Naval Base.

There has been much speculation and debate over which of these ports might be the location for additional Chinese military bases besides Doraleh. Although the available data and understanding of the decision-making criteria are limited, certain measures provide some insight.

As seen in the development of Doraleh, in which Chinese companies held 23% of the stakes, the size of Chinese shareholding alone is an inadequate factor. Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that Chinese companies hold stakes of 50% or more in these West African ports: Lekki (54%); and Lomé, Togo (50%).

As seen in the development of Doraleh, in which Chinese companies held 23% of the stakes, the size of Chinese shareholding alone is an inadequate factor. Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that Chinese companies hold stakes of 50% or more in these West African ports: Lekki (54%); and Lomé, Togo (50%).

Previous PLA engagement is another consideration. Of the 78 African ports with known Chinese involvement, 36 have hosted PLA port calls or military exercises. This demonstrates that they have the design features to support Chinese naval flotillas, potentially making them suitable considerations for future PLA Navy bases. Not all of these have the proven physical specifications to berth PLA vessels, however. These factors include the number of berths, berth length and size, and capabilities for fueling, replenishment and other logistics.

Beyond the physical specifications are political considerations, such as strategic location, the strength of a government’s party-to-party ties with China, its ranking within China’s system of partnership prioritization, membership in China’s BRI network, and levels of Chinese foreign direct investment and high-value Chinese assets. Commonly ignored, but no less important, is the strength and capacity of public opinion to shape local decisions.

Whose Interests are Advanced?

Former PLA Navy Cmdr. Wu Shengli noted that “overseas strategic strongpoint” ports always were envisioned as platforms for building an integrated Chinese presence. In other words, China has been highly strategic in its development and management of African ports to advance its interests as part of its geostrategic ambitions. Looking to the future, it can be expected that China will seek to increase its role in building African ports to expand its ownership and operational control toward commercial, economic and military ends.

African debates on Chinese-built or operated port infrastructure tend to focus on the impact these ports can have on advancing Africa’s economic output by improving efficiencies, reducing the costs of trade and expanding access to markets. Although some concerns are raised as to the implications these projects have on Africa’s increased debt burden, rarely do these discussions publicly address sovereignty or security, or the role that commercial platforms could play in Chinese basing scenarios.

The heightened pace of China’s military drills and naval port calls in Africa in recent years has brought increased attention to these issues in the African media, think tanks and policy discussions. The growing militarization of China’s Africa policy is stoking concerns about the implications of more foreign bases in Africa. Some are concerned that Chinese basing scenarios could inadvertently draw African countries into China’s geopolitical rivalries, undermining the continent’s stated commitment to nonalignment.

Ensuring that Chinese port investments do not go against African interests will require that African governments, national security experts and civil society leaders grapple with the policy implications of these choices. Beyond the straightforward desire to expand export infrastructure are tangible issues of maintaining fiscal prudence, safeguarding national sovereignty, avoiding geopolitical alignments and advancing a country’s strategic interest.

About the author: Paul Nantulya is a research associate with the Africa Center for Strategic Studies. His areas of expertise include Chinese foreign policy, China/Africa relations, African partnerships with Southeast Asian countries, mediation and peace processes, the Great Lakes region, and East and Southern Africa. The original version of this article was published by the Africa Center under the title “Mapping China’s Strategic Port Development in Africa.” It can be found here: https://africacenter.org/spotlight/china-port-development-africa/

Chinese Control Exports Riches, Imports Trouble

Chinese port involvement in Africa goes beyond political and military concerns. The control China exerts at every stage of development and operations also can adversely affect life for citizens across the continent.

It starts with what maritime expert Ian Ralby calls “elite capture,” through which China attempts to co-opt key authorities, who, in turn, surrender their fiduciary and governmental duty in service to themselves. Once China undermines “the structures of governance in a country, it opens the doors to anything else,” he said.

Ralby, CEO of I.R. Consilium, a global maritime and resource consultancy, told ADF that once China has control of ports, it can control what comes into and out of the continent — all to its own benefit. “That’s where we have to be very clear, that Chinese overseas investment is never altruistic,” he said. “It is never for development and aid to the benefit of the jurisdiction in which they are operating. It is for the development, benefit and advancement of China itself.”

Nations first lose sovereignty through egregious loan deals to finance infrastructure, including ports. Once port deals are struck, China brings over its own workers and operators to the exclusion of locals. Some of these workers are political prisoners. After ports are built, areas around them can attract unsavory elements, such as prostitution and predatory businesses. China does nothing to mitigate this, Ralby said.

Once in control, China can open nations to illicit trade in drugs, weapons, even people. But it’s not just about what China brings in. It also uses port control to take things out of the country, such as valuable minerals and wildlife resources, Ralby said.

The nation’s footprint on the continent includes the large-scale plunder of fishing resources, timbering and logging, the wildlife trade, and mining operations.

“It’s monopolized its ability to extract from the African continent and move what it has extracted via roads that it has built, to a port that it has built and operates, to ships it owns and operates, back to China for the ultimate goal, which is to advance China,” Ralby said.

It might be tempting to think of improved, modern port facilities as a boon to host countries. But China’s involvement at every level, particularly operations and management, makes these facilities more of a benefit to China. For example, African ports tend to be comparatively small, which can cause queues of up to 30 vessels at times. If a Chinese company owns or operates the port, it can allow Chinese ships to skip the queue, thus unfairly benefiting them at the expense of domestic or other foreign ships.

Another major concern is the ramifications of China establishing another naval base on the continent, especially on the West African coast. One thing seems certain, Ralby said: African nations should not expect any direct security benefit from an enhanced Chinese military presence. Even though China has a base in Doraleh, Djibouti, its Navy “has not responded to a single incident” in the Red Sea as Houthi rebels wreak havoc, he said.

Ralby said available evidence shows that the Chinese Navy lacks the competence and desire to assist partner nations in times of peril.

What African nations can expect China to do, Ralby said, is to “provide security for their own supply chains” as they siphon valuable resources from the continent, allowing China to advance itself and “provide protection against domestic efforts to enforce the rule of law.”