In the nearly two decades since the African Union launched its mission to stabilize Somalia, one weapon has wrought the most damage. Again and again, the terror group al-Shabaab has used improvised explosive devices to shatter peace, spread fear and derail progress.

Terrorists plant the bombs, also known as IEDs, on main supply routes, in crowded markets and everywhere in between. The United Nations Mine Action Service called these homemade bombs a “$20 problem requiring a million-dollar solution.”

In 2007, the first year of the AU mission, 57 IED attacks were recorded in Somalia. In 2023, 600 IED attacks resulted in 1,500 deaths. Early in the insurgency, it might take the terror group a year to construct a vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (VBIED) capable of killing dozens. By 2023, al-Shabaab was detonating multiple VBIEDs a month.

“Al-Shabaab now considers IEDs as their main weapon of choice,” Col. Wilson Kabeera, commandant of the Uganda School of Combat Engineers, told ADF. “It has evolved over time.” Kabeera added that early bombs were simple 5-kilogram explosives triggered by a pressure plate while today’s IEDs can contain an explosive charge of 100 kilograms.

Somalia is not the only IED hot spot. Terrorists are using IEDs in Mozambique, across the Sahel and in the Lake Chad Basin. In Nigeria, IED attacks, mostly by Boko Haram, are the deadliest form of violence, accounting for 84% of civilians killed in terror attacks. In the second half of 2024, Nigerian extremist groups made headlines by returning to the tactic of suicide bombings. West Africa has seen a dramatic rise in IED attacks from four incidents in 2013 to 540 in 2021.

Between 2015 and 2022, IED attacks multiplied in East Africa as terror groups targeted civilians and military personnel.

Experts believe it is incumbent on any military facing an insurgency to invest in counter-IED training and technology, especially since civilians are the overwhelming majority of victims.

“The hazard to civilians is pretty large,” said Sean Burke, counter-improvised explosive device (C-IED) program manager at U.S. Africa Command. “So, the problem set is that if you’re trying to protect your population and establish or maintain a stable country, this is one of the hazards that definitely has to be addressed.”

A Step Ahead of Adversaries

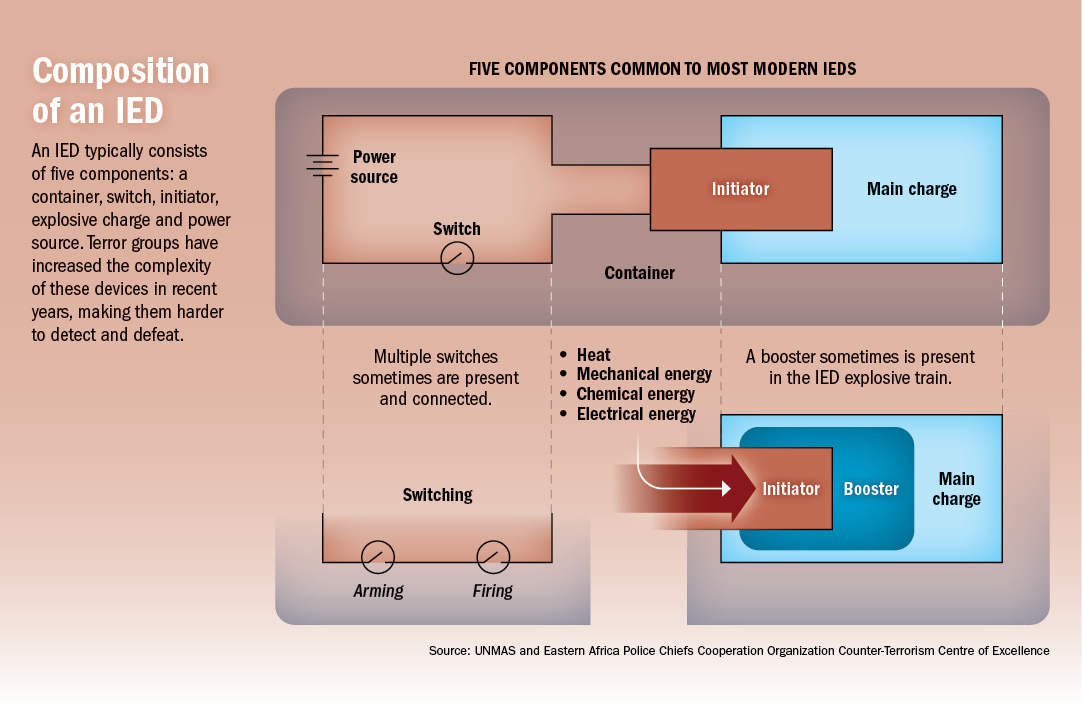

An IED typically is defined as any explosive that is not manufactured industrially or produced in a standard fashion. It is often made by manually assembling components that are diverted from their intended use.

The use of IEDs on the battlefield dates to the 16th century, when soldiers dug pits known as “fougasses” and filled them with explosives in order to light a fuse and detonate them when an enemy came near. Over the years, as industrial explosives such as TNT, nitroglycerin and black powder became widely available, the practice became more widespread. IEDs have been used in most conflicts since the 19th century. They are a favored tool of insurgent groups globally engaged in asymmetric warfare.

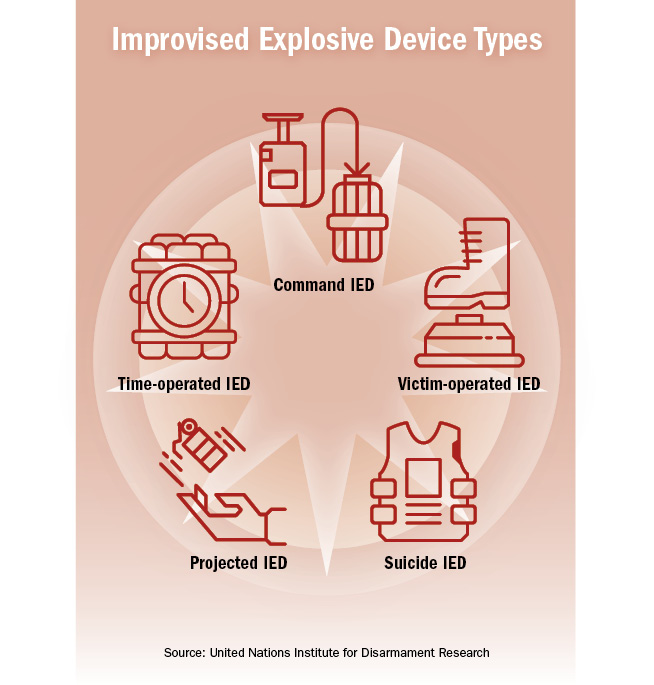

IEDs typically include several basic components: a power source, a switch that arms the device, an initiator that lights it and an explosive agent. The general categories are:

A command IED, in which the perpetrator controls the explosion.

A time-operated IED, which is designed to explode at a given time and is set either through electrical or chemical means.

A victim-operated IED, which is activated by a victim stepping on a pressure plate or breaking a trip wire.

A projected IED, which is launched at the intended target.

A suicide IED, which is detonated by attackers to kill themselves and others.

Kabeera said the devices used today are cheaper, deadlier and harder to detect. Many are radio-controlled and have an explosive charge designed to launch a shaped penetrator that can pierce vehicle armor. The trigger can be something as widely available as a motorcycle alarm or mobile phone.

The intent is to cause the maximum amount of carnage and panic. Some bombs used in Somalia are designed to activate when security forces pass a metal detector over them. In other cases, secondary IEDs are strategically placed to target medical personnel and first responders after an initial blast.

C-IED specialists must constantly race to stay a step ahead of adversaries in terms of technology and tactics.

“Training and retraining should endure all through the operation to offset the human tendency of complacency,” Kabeera said. “Through sensitization, trainings, refreshers and threat awareness to both the C-IED operators and the infantry troops, everybody is situationally aware and knows what to do.”

Uganda has pushed to improve its training. All Uganda Peoples’ Defence Forces (UPDF) Soldiers deployed to Somalia take courses on IED and ordnance disposal, awareness courses on explosive hazards, and how to search routes for IEDs. There are refresher courses throughout the deployment. The UPDF also is training experts in post-blast investigation, combat trauma care and electronic countermeasures, among other things.

On the battlefield, Kabeera said, troops have adopted an approach that incorporates intelligence gathered from civilians and aerial surveillance. There are IED briefings to troops before any operation, and strategies to protect liberated areas from IED attacks.

“The progress being made by UPDF has been very effective, however, not sufficient to mitigate and defeat the terror groups on its own capability without partner involvement,” Kabeera said. “More support from Allies and Partners is required, and mentoring using subject matter experts to UPDF personnel to avoid skill fade is essential. However, the UPDF C-IED approach has armed our teams with the correct attributes to defeat IEDs.”

Across Africa, militaries are investing in C-IED training with advanced curricula, new facilities and technology. The U.S. and other partners, including France, Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom, have tried to standardize training by using modules solely from the U.N. IED-defeat curriculum, which allows for continuity of training between partners.

Tunisia has emerged as a continental leader and is making progress toward having Africa’s first U.N.-certified C-IED Center of Excellence. The center in Tunis is fully staffed by experts and capable of teaching the full suite of C-IED and explosive ordnance disposal courses.

Kenya is building a C-IED training center in Embakasi at its Humanitarian Peace Support School, which already offers courses to military students from across the continent. In August 2024, Kenya hosted the 6th Counter Improvised Explosive Device Conference.

Senegal is expanding C-IED training at its Demining Training Center in Bargny and is building a new military engineering school at the same location. In 2023, Senegalese deminers became the first to complete the U.N. Intermediate Improvised Explosive Device Defeat course with the assistance of U.S. Army instructors.

Advocates hope the rise of local expertise will allow teams of African instructors to export C-IED knowledge across the continent and that new African facilities will allow greater access to training.

“They’re starting to share the burden of training,” Burke said. “So that’s the significance of it. It shows that our African partners have the expertise.”

The most difficult aspect of C-IED work is interrupting the supply chain that allows extremist groups to produce the devices. “Attack the network” training is difficult because many components used in simple IEDs also have civilian applications. Items such as electrical initiators, detonating cords, cellphones and explosive precursors such as ammonium nitrate are needed for construction, farming and other commerce. However, experts say, targeting the IED supply chains, bombmakers, financiers and workshops is the only way to stop the problem.

“If you don’t actually try to get after the bad guys and the suppliers and the financiers of all of the folks that are required to support those kind of operations, then it’s a Whac-A-Mole game, and you’re never going to get in front of it,” Burke said.

In Somalia, certain explosive materials, precursors and items such as detonators are monitored and require special importation permits. But importation limits have had little effect. One assessment found that about 60% of explosives used in al-Shabaab attacks near the Kenyan border had been obtained through capturing unexploded ordnance such as artillery shells or theft of military ammunition.

“Al-Shabaab operatives do not need to go abroad for basic IED materials, most of which are sourced locally. In addition to unexploded ordnances that litter the country after a quarter century of conflict, al-Shabaab gets IED main charges from its enemies,” Daisy Muibu and Benjamin Nickels wrote for the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point. “Through seizure and purchase of materiel available in Somalia, al-Shabaab has all the pieces it needs for IEDs.”

C-IED practitioners say they need forensics training to trace the source of explosive components and better stockpile management and accounting to make sure military munitions do not fall into enemy hands. There also is a need for regional partnerships to track suspicious importations or movement of goods across borders.

“A holistic approach is needed and, to be effective, the approach should cover a broad geographic region,” researchers with the Small Arms Survey wrote in a report on the trafficking of explosive device components in West Africa. “Without a synchronized and common approach at the regional level, traffickers will simply identify new clandestine sources and take advantage of weak and inconsistent laws and regulations to procure the materials they seek. There are a few downsides to a regional approach and many potential benefits.”