ADF STAFF | Photos by ATMIS

In the yearslong war against violent extremism across Africa, countries have tried a range of approaches. Multinational United Nations peacekeeping missions have toiled in the Sahel and elsewhere for years, with mixed results.

Similarly, African Union and other regional forces have worked tirelessly to bring peace and stability to places such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, northern Mozambique and Somalia.

Each effort provides a frustrating mixture of successes and failures, advances and retreats. The limitations of military forces are clear: They can bring to bear lethal force and guarantee a degree of protection for the civilians and the governments they protect. But they can’t stay forever. Often, they can’t even stay in one place for an extended time as they pursue violent extremists to their hideouts.

Police forces, on the other hand, have more permanent national and local ties. Their charge is to protect the people at all times. They also investigate crimes, arrest perpetrators and gather evidence, starting the process that eventually leads to prosecution. Their effectiveness at all of this can be informed by a time-tested process known as community-oriented policing.

“Community policing sits at the nexus between state security actors, local communities and civil society,” Dr. Anouar Boukhars, professor of counterterrorism and countering violent extremism at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies (ACSS), said in a virtual academic program on the subject in 2020. “Effective community policing cannot be imposed simply as a strategy or a tactic for countering violent extremism … it’s an ethos that must be infused into the culture and practice of security actors.”

Different types of community policing have been tried across the continent, including in Kenya, Somalia and Tanzania to name but a few. The approach was valuable in Kenya after four al-Shabaab gunmen killed 148 people and wounded nearly 80 others at Garissa University on April 3, 2015.

Kenya has a community policing model called “Nyumba Kumi,” which is Swahili for “10 households.” In this system, household clusters work together to keep watch and report suspicious matters to police. Mohamud Saleh, who was appointed the new regional coordinator after the Garissa attack, successfully leveraged the system to build trust and improve security in a region suspicious of police.

Saleh set up a direct line so the public could reach his office, according to Saferworld, a global peace and security organization based in London. He also established direct lines to police quick response units to access information for action. If an attack occurred, authorities would hold a public forum known as a barasa to identify underlying issues before responding with force.

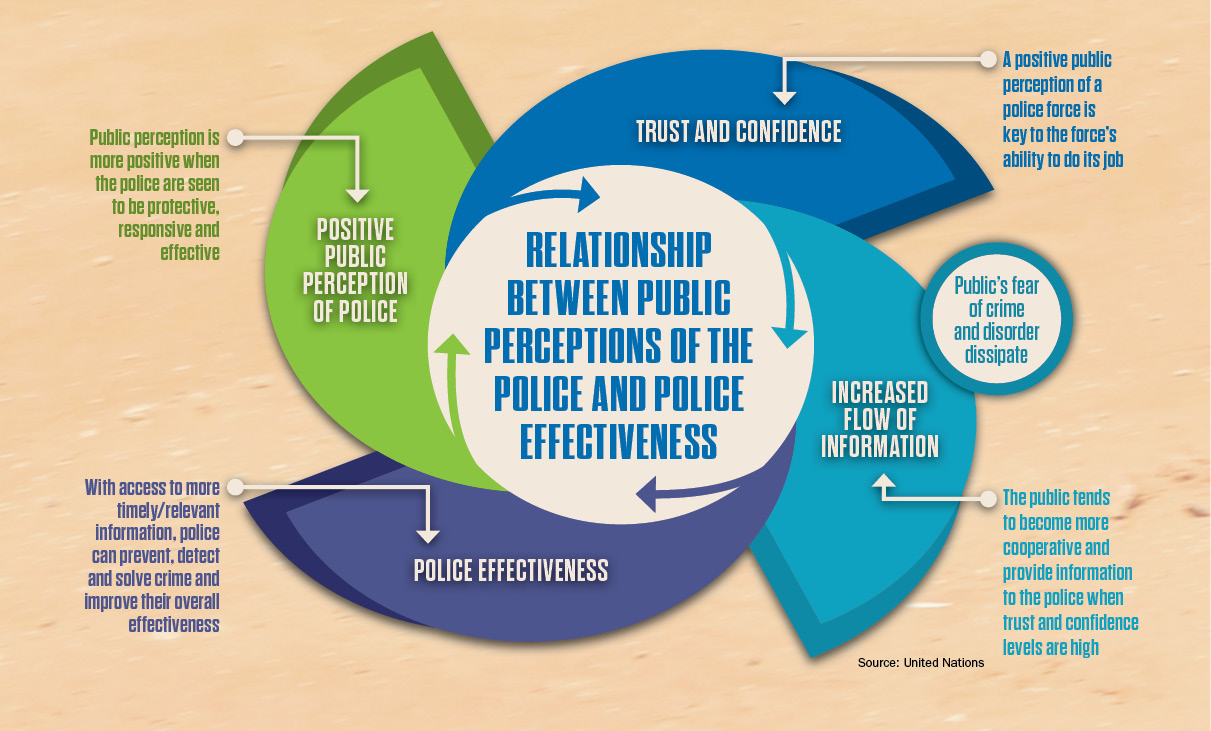

The system replaced “a forceful approach with one that is based on trust and accountability that builds relationships with local communities to gain intelligence,” Saferworld reported. Stronger bonds between police and civilians can avoid grievances that drive some people to extremism.

ELEMENTS OF COMMUNITY POLICING

ELEMENTS OF COMMUNITY POLICING

Community-oriented policing can look different based on location and context, but it typically includes some variation of five core principles: problem-solving, empowerment, partnership, service delivery and accountability.

The Police Service of Northern Ireland adopted those five principles, which were adapted from the model developed by the South African Police Service after apartheid ended, according to a paper by Neil Jarman, a research fellow at Queen’s University in Belfast, Northern Ireland. The approach reorients police work from a reactive to a proactive posture while empowering civilians to participate in addressing security issues.

Meressa Kahsu Dessu, a senior researcher with the South Africa-based Institute for Security Studies, highlighted the principles in a June 2024 blog post for the Wilson Center. “These elements guide the police officers to establish and build partnerships with local populations based on mutual understanding, trust, and respect,” he wrote. “They engage regularly with local residents, community groups, business owners, and other local stakeholders.”

For community-oriented policing to be successful, it must be driven by local communities and include all elements of society, such as women, young people and others, Phyllis Muema, executive director of the Kenya Community Support Centre, said in the ACSS virtual program. “Our principles of community policing are ideally founded on the principle that policing is by consent, not by coercion,” she said. “It must be something that is driven by the local communities.”

POLICING IN PEACEKEEPING

A 2014 United Nations Security Council resolution recognized the importance and effectiveness of community-oriented policing, and that emphasis is prominent in the U.N.’s guidelines for how police should operate in peacekeeping and political missions.

U.N. missions are supposed to assign police officers to “manageable patrol areas” so that civilians can get to know them by name. Police contingents should include female officers and consult community members about their needs and design programs accordingly, the guidelines state. A “consultative committee” in each patrol area should include “carefully vetted” men and women who are representative of the community and whose interests will not undermine mission success. Committees need to meet at least once a month. Police officers should share crime information with the committees and the media in a timely way.

The African Union also has recognized the importance of community-oriented policing. Officials serving in the recently concluded AU Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS) emphasized the model in training throughout 2024. In August, more than 100 Somali Police Force (SPF) officers finished a month of community policing training.

ATMIS and SPF officials organized the training, which focused on the core components of community policing, its legal framework, and the protection and support of children, among other things.

“Somalia’s security landscape is complex, and therefore it is important to have a tailored approach to community policing,” Sivuyile Bam, deputy head of ATMIS, said in a news release. “We must continue to listen to the concerns of the communities, understand their needs and work together to address them.”

ATMIS Police Commissioner Hillary Sao Kanu of Sierra Leone said her officers and the SPF had jointly conducted 18 capacity-building training events across the country benefiting 352 Somali police officers, including 162 women, since January 2024. “Today’s event is therefore significant to our collective efforts to improve on safety, trust and cooperation between the police and the communities that we serve in Somalia,” she said at an August 31, 2024, graduation ceremony.

Just a few days later, officials began construction of a new police station in Somalia’s Darussalam district. The station is intended to help Somali police officers fight crime while strengthening community relations in the area.

“Policing is a shared responsibility, and ATMIS police component is here to support our SPF counterparts to bring policing to the doorsteps of community members and help protect their human rights,” Samuel Asiedu Okanta, mission police training and development coordinator, said in a news release. “This facility will help to prevent crime and enhance policing services in this community.”

In October 2024, ATMIS trained 12 SPF officers and 24 community leaders in Dhobley on police station management, community policing, human trafficking and crime prevention. Mission Sector 2 commander Brig. Seif Salim Rashid of Kenya said bringing together police and civilian leaders would provide more effective security. Dhobley District Commissioner Hassan Abdi Hashi agreed.

“Community members and law enforcement can build a stronger, more resilient community by working together to address safety and security challenges,” Hashi said, according to a news release. “By sharing the lessons learned from this training, we can empower our communities and create a ripple effect of positive change.”

Unlike ATMIS, not all counterterrorism missions allocate adequate resources for a police component. Such has been the case with the Multinational Joint Task Force, which targets Boko Haram and Islamic State group extremists in the Lake Chad Basin. A 2023 report for the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs indicated that although troops have successfully cleared areas and restored stability, the mission’s lack of police capability has kept it from protecting and holding cleared areas to sustain stability operations.

This forces “the military to remain present in some areas once security has been restored to conduct policing tasks and ensure the safe entry and performance of stabilization and humanitarian activities,” the report states. “However, the military does not have sufficient capacity to operate at this level as it causes the exhaustion of its already limited resources that could be used in further offensive operations elsewhere.”

The AU and its member states need to prioritize community-oriented policing in peace operations, Meressa wrote for the Wilson Center. “Community members are best positioned to recognize suspicious activities in their communities — including radicalization and extremism activities — and to inform the police officers promptly,” Meressa wrote. “Through such stronger community policing partnerships, the police can proactively detect suspicious activities, solve crime and violence problems, and build communities’ resilience to violent extremism.”